On the night of October 12, 2002 in Bali, Gatut Indro Suranto was driving home with his coworkers after a business dinner. As they rolled in front of Sari Club in Kuta, they heard a loud explosion.

That night, two bombs detonated by members of the al Qaeda-linked Jemaah Islamiyah terrorist group ripped through Paddy’s Pub and Sari Club, killing 202 people and injuring more than 200 others.

“My car was the seventh vehicle behind the Mitsubishi L300 van in which the bomb was planted. I was taken to Sanglah General Hospital to undergo surgery and [I was] unconscious for half a day,” said Gatut.

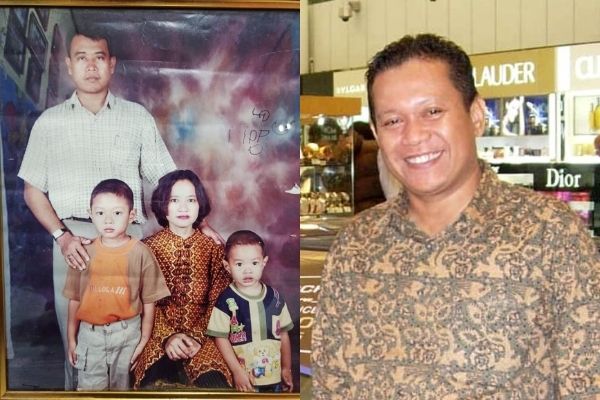

Now 51, Gatut spent two months in the hospital because of burn injuries and shrapnel wounds in his hands, face and chest. Several tendons in his right index finger and left knuckle ruptured, making it difficult for him to grip.

The injuries also affected his eyesight, as he now says he has trouble reading off a cellphone screen and printed text with the naked eye. His right ear has also been impaired.

Unlike Gatut, Mahanani Prihrahayu, 53, was not a direct victim of a terror attack, yet her subsisting pain still affects her to this day. Her husband, Slamet Heriyanto, was killed in the August 5, 2003 suicide bombing at Jakarta’s JW Marriott Hotel, where he worked as a security guard.

Amid live news coverage of the incident, Mahanani did not immediately learn of her husband’s fate as she was swamped with work as a machine operator at an electronics factory. She only became aware of the attack when she got home.

“A media outlet called my landline, notifying me that Slamet Heriyanto was at Cipto Mangunkusumo Hospital. At that time I still couldn’t believe it. Finally, my brother went to the hospital and was told that my husband had died,” she recalled.

After the tragedies, Gatut and Mahanani struggled financially but received little to no significant support from the government for a long time after the attacks. Along with other victims, they joined the Family of Survivors Foundation (YKP) to fight for their right to legally-mandated government compensation. After years of struggle, they were finally granted financial compensation recently, along with 213 other victims and/or their families.

Life after the tragedy

Getting discharged from Sanglah was only the beginning of Gatut’s misery. He was required to go through numerous rounds of surgery in Denpasar and Australia, funded by the Bali provincial government and the Australian Red Cross, respectively.

“With shrapnel embedded in my chest and shoulder, I underwent major surgery seven or eight times. In 2005, I was sent to Australia because there was shrapnel obstructing my airways,” Gatut said.

As a result of his serious injuries, Gatut was forced to retire early from his job as a sales manager to focus on his recovery. His wife still works for a private firm in Denpasar, but Gatut acknowledged that his family does not have the financial means to pay for his children’s schooling so they have had to rely on his sibling for financial support. For the better part of the past year, he has been staying at his close relative’s house in Mojokerto, East Java to undergo eye treatment at a hospital in the city.

Meanwhile, a few years after the tragedy, Mahanani was made redundant from her job. But there was nowhere to go but up after she hit rock bottom, as she managed to set up and run a small kiosk selling stationery, cold beverages, and snacks near a school in Citayam, Bogor regency for the past 10 years.

A charity foundation has been giving Mahanani tuition assistance for her sons, but that well dried up when they graduated from high school. College for them, then, had to come with hard work.

“I told my sons to work after they completed senior high school. Thank God, my firstborn pays his own [college] tuition while working full-time. He is now in the seventh semester. His brother just started working a few months ago, but he did not enroll in college,” she said.

“The value of compensation is not comparable to our suffering. But during the pandemic, this is quite helpful. Even though the attack happened many years ago, we are grateful because the government still cares about us.”

For Gatut, being in the same room as the terrorists was one of the most painful experiences he’s had to endure since the attack. And he had to do just that when prosecutors asked him to testify at the Bali bombing trial in Denpasar in 2003.

“As a human being who was hurt, I held a grudge. But because I believe that what they did was wrong, God would repay them for what they did to us,” he said.

Many years later, Gatut had the opportunity to be at the same event with Ali Fauzi, a former bomb-making instructor who was unaware of the plot but had taught numerous people, including his convicted brothers Amrozi, Ali Gufron, and Ali Imron.

They were invited by the Alliance for a Peaceful Indonesia (AIDA) to the event, during which survivors and former terrorists engaged with school students to expand their understanding of the impact of violent extremism.

“Both of us shared our experiences. The purpose was to show that what Ali Fauzi did was wrong, and the attacks have not only affected the victims but also their families,” said Gatut.

Mahanani has also been involved in the same program and admitted that it was not easy to let go of the past.

“I met with a former terrorist, but I still had resentment and I didn’t want to forgive him. After he apologized, regretted his actions, and said he had changed, I finally forgave him,” she said.

“Adding more violence will not end the violence. If I keep remembering what happened in the past and maintain my hatred, I won’t be psychically healthy like I am today.”

Fighting for compensation

Government Regulation (PP) No. 35 on compensation, restitution, and assistance to victims and witnesses of terrorism, which was passed this year, defines recipients as people impacted by criminal acts of terror that occured from the enactment of the Government Regulation In Lieu of Law (Perpu) No. 1/2002 on Terrorism Eradication to the issuance of Law No. 5/ 2018. on Terrorism Eradication. A previous PP on compensation, restitution, and assistance passed in 2018 only defined recipients as people impacted by terror attacks after its issuance.

Old legal frameworks on counter-terrorism and victim protection clearly state that survivors are entitled to compensation. However, because of their poor implementation, not all victims have received what they are entitled for.

The Witness and Victim Protection Agency (LPSK) has granted compensation to a number of victims of past terror attacks before the newest government regulation was issued. Nevertheless, the payment was made only after the terror convicts were sent to prison.

In an interview conducted by Tempo.co in 2017, former LPSK chairman Abdul Haris Semendawai said that from the 300 terror attacks in Indonesia from 2002 to 2016, courts seldom order compensation for victims. On the rare occasions that compensation is ordered in court rulings, payments are often held back as the government did not have a specific budget allocated to victim compensation.

YKP secretary general Vivi Normasari said that she and her peers have been fighting for the fulfillment of victims’ rights long before the organization was founded.

“My friends and I have visited the Ministry of Social Affairs, Ministry of Health, and provincial governments (to inquire about our rights). The National Counter-Terrorism Agency (BNPT) and LPSK advised us to establish a foundation to strengthen our position,” said Vivi, who is also a survivor of the 2003 JW Marriott Hotel bombing.

YKP was founded in Jakarta on August 5, 2018. One of their missions is to inform terror victims about the services available to them and their entitlements.

“Many victims who are not the members of our organization know nothing about government’s support for victims of terrorism. We search for them using data provided by hospitals or foundations that gave assistance after the attacks,” Vivi said.

Mahanani, who is also a member of the YKP, lauded the benefits of the service for victims.

“Two years ago, LPSK offered psychological assistance to secondary victims. For one year, I consulted a psychologist. This alleviated [the burden off] my mind,” she said.

Victims’ entitlement for government support was further strengthened by PP no. 35, which includes a provision ensuring that past victims and their next of kin can file a claim for compensation through LPSK without having to wait for a court order.

After a long wait, on Dec. 16, 215 surviving victims and victims’ next of kin, including Gatut and Mahanani, obtained their compensation. Each family whose close relatives were killed in a terror attack received IDR250 million (US$17,761), while surviving victims with grave, moderate, and minor injuries received IDR210 million (US$14,919), IDR115 million (US$8,170), and IDR75 million (US$5,328), respectively.

While this was a step in the right direction, the number of recipients so far account for only a small fraction of victims.

“The National Counterterrorism Agency (BNPT) and the Special Detachment 88 Anti-Terror Police (Densus 88) are still collecting data on victims. There are roughly 900 people who have not received compensation, and this number can add up,” said LPSK deputy chair Susilaningtias.

YKP is finding itself in a race against time to assist past survivors as the foundation has only until June 22, 2021 to apply for compensation for victims. One of the requirements for compensation is a BNPT decree confirming a recipient’s status as a victim of a past act of terrorism.

“The decree is a must, even if the attack occurred more than ten years ago. In the hospitals, many patients’ medical records are no longer available. The National Police possess data on the numbers of victims, but no details on their names,” Vivi explained.

The absence of medical records in the hospital complicates the assessment process, especially when determining the severity of victims’ injuries. For this reason, LPSK is working together with the Indonesian Forensic Doctors Association (PDFI) to solve this problem.

“Many hospitals no longer keep victims’ medical records, and that’s why the forensic doctors have to assess [victims] more than once,” explained Susilaningtias.

Vivi and Mahanani say they appreciate this victim-sensitive policy.

“The value of compensation is not comparable to our suffering. But during the pandemic, this is quite helpful. Even though the attack happened many years ago, we are grateful because the government still cares about us,” said Vivi.

“This is an immeasurable fortune for past survivors. Hopefully this compensation is useful and brings blessings to us. We would like to thank the president, BNPT, and LPSK,” added Mahanani.

Gatut says he has been put at ease for at least the near future. “I will use this money to pay for my medical expenses and my kids’ tuition fees,” he said.