With additional reporting by Andra Nasrie

Warning: This story contains graphic descriptions of sexual harassment.

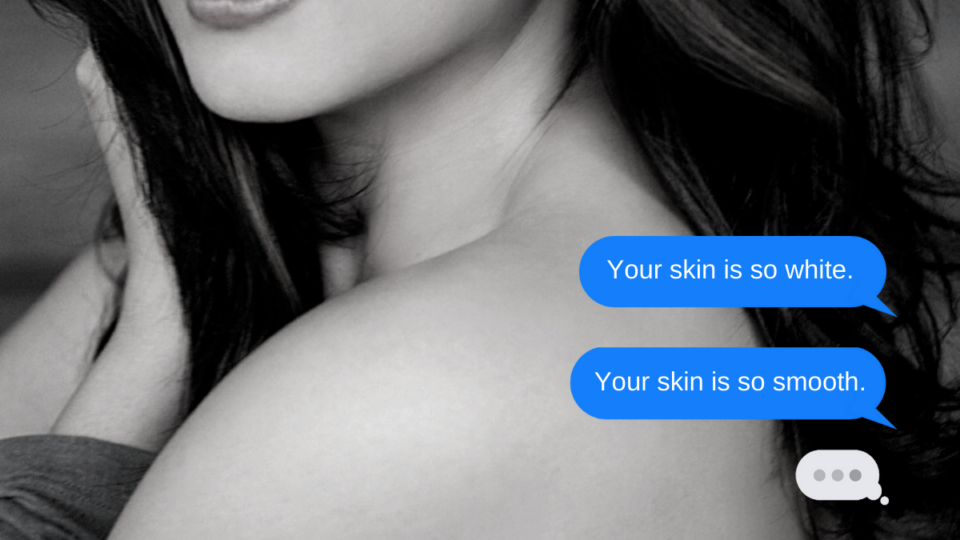

It started with comments on Instagram that, some men might argue, seem quite innocent.

“Your skin is so white.”

“Your skin is so smooth.”

Soon enough, the comments became increasingly bold and more obscene. It wasn’t long before men started sliding into her Instagram DMs with unsolicited dick pics.

Arnia*, a 20-year-old social media influencer, said this sort of harassment has been par for the course in her digital life since she was 16.

This was not the social media engagement she had in mind. A self-confessed fashion enthusiast who is active in urban fashion communities, Arnia began making a name for herself in 2017. Through no fault of her own, she said the majority of people who started following her on Instagram happen to be sleazy men.

“My followers were 80 percent male, and I noticed they like to comment on my skin,” she said.

As her popularity grew, the sexual harassment intensified.

“I got reposted by a lot of weird accounts [with handles containing phrases] like ‘Chinese-Indonesian women’s white armpits’ [on Instagram and Twitter]. From then on, people who followed those weird accounts followed me as well… and [these] people sent me dick pictures,” she said.

“I hate when they do that,” Arnia added. “I mean, like, I was 16, why would you sexualize a 16-year-old, you know? That’s fucked.”

As a Chinese-Indonesian woman, Arnia is well aware of where her gender and race place her in the lopsided power dynamics of online sexual abuse cases. As is common in Asia, light skin color is fetishized in Indonesia due to, among others, a relentless multi-million dollar skin bleaching industry and a pop culture that favors women with fair complexions.

In Indonesia, that fetishization is also bound to generations of resentment towards the racial minority, with the mass rapes of Chinese-Indonesian women in 1998 being one of the darkest example of that hatred being acted out in the country’s history.

Like many other victims, there is often a strong racial element in the online sexual abuse women like Arnia endure. Many are referred to online by “amoy,” a derogatory term referring to Chinese-Indonesian women that is still widely used in everyday conversation and in online forums to this day.

Monika Winarnita, an Indonesian studies lecturer at Australia’s Deakin University, stressed the importance of stamping out racist and sexist terms from public discourse.

“Indonesia is part of the global community that values humanity’s progress towards gender equality and minority rights as exemplified in [the] #MeToo, #Blacklivesmatter, and #StopAsianHate [movements],” Monika said.

“The derogatory term amoy has historically been experienced as both racist and sexist for the Chinese-Indonesian female as exemplified in reporting during the May 1998 rapes and its fetishization afterwards in popular cultural representation of the event. No equivalent terms exist for Chinese-Indonesian men.”

Army of perverts

Arnia is just one of many Chinese-Indonesian women whose content is often stolen and bastardized to become fodder for a virtual army of predators who engage in disturbing forms of sexual abuse online.

After some six months of going deep into the dark world of these online groups, Coconuts tallied thousands of Twitter accounts that regularly shared intimate photos and videos of Chinese-Indonesian women. Often, they repurposed those images to create frighteningly vulgar and invasive content of their own.

Of those thousands, we found 155 accounts focused specifically on abusing, sexualizing, and fetishising Chinese-Indonesian women. Many of those accounts had significant social media followings, ranging from hundreds to thousands. All of these accounts are still very active, with some newly created in 2022.

The perpetrators hide their true identities and often change their handles to avoid prosecution or getting reported by the victims. Many use backup accounts they can immediately switch to if their main account gets suspended.

If they were an army, then one particularly relentless predator, who went by three different handles from 2021 to 2022, would be one of their generals. Some know him as @krokink, while other times he goes by @rosseshinn. To our knowledge, he last went by @aesshinn before we lost track of him; perhaps after changing his name yet again.

A victim of this prolific pervert told Coconuts that she had reported him over and over again, hoping for Twitter to suspend him from the platform for good. She said she has lost count of the number of times she flagged him, only for him to get away by re-spawning under a new name.

We tracked his first account @krokink, which had 975 followers at the time, starting in October 2021 but found that his Twitter activity went all the way back to 2019. An Aug. 4, 2019 tweet of his read: “About this account: I masturbate, share contents and fantasize to mostly asians. This account mainly consists of sexual lash out, fantasy, and imaginative sexual diary. Feel free to invite or initiate a group jerk off to any asian girl of your choice with me :)”

“If I know you in real life I’ve probably masturbated to you at least once,” he proudly boasted in his Twitter profile.

@krokink was very active in sharing photos of Chinese-Indonesian women, particularly influencers. He regularly hosted so-called “jerking sessions” with his followers via Twitter Spaces during which they would share photos of women, who they would proceed to slut-shame and degrade for their perverted pleasure. Like a sick game, he also fished for likes and retweets from his followers, promising to reward them with unpixelated photos of victims and even links to their social media pages.

But the most disturbing were tweets that expressed rape fantasies, many of which received enthusiastic messages of encouragement in the replies from his followers.

By Jan. 12, 2022, he was going by the handle @rosseshinn and had 1,374 followers. It appeared that his previous account had been blocked, prompting him to exercise caution in accepting followers. Specifically, he said he would block users who set their profile to private out of concern that his victims or other good samaritans might be lurking to flag his account.

On March 7, 2022, @rosseshinn had disappeared from Twitter, presumably after getting flagged for violating the platform’s terms and conditions. But another account, @aesshinn, appears to have been used as one of his back ups. Active since December 2021, this account used similarly broken English and targeted Chinese-Indonesian women.

Other accounts we investigated were just as prolific.

One labeled himself a “cum-tributer,” which is exactly as repulsive as it sounds, and a “ratings agency,” reposting private photos of many Chinese-Indonesian women while scoring their physical attributes.

“She’s what I call ‘elegantly beautiful’. She looks like someone from a good wealthy family. Which is why she deserves to be f8ucked senseless. Just straight up rough, hard and dirty; something she might never experience in her life before,” the account tweeted about one victim.

Another account, which has been active since October 2021, tweeted about another victim: “So nice to rape her together until we cum all over her body,” on Jan. 25, 2022.

And then there are the impostor accounts, who assume the identities of their victims to engage in sexual fantasy role-play for their own and their followers’ gratification. Often, these accounts delve into racial dynamics; specifically, they act out scenarios in which Chinese-Indonesian women become submissive to the desires of pribumi (a loose term to describe native Indonesians) men. That, in itself, offers a major clue as to the racial identity of the people behind these accounts.

One impostor account, which joined Twitter in June 2021, currently has 11.4 thousand followers and is still very active. On Feb. 10, 2022, role-playing as a Chinese-Indonesian woman, he tweeted, “A Chinese slut should obey native Indonesians’ dick.”

Indonesian law leaves victims in limbo

These accounts only represent the tip of the sleazy iceberg. They make up a highly coordinated, highly active community, obtaining victims’ personal images – mostly from social media and content sharing platforms – before trading them among each other. The images then spread like wildfire; once one is shared, it seems nothing can stop its circulation.

This never-ending non-consensual sharing of intimate images shows a systematic failure to protect sexual violence victims in Indonesia, both offline and online.

According to the National Commission on Violence Against Women (Komnas Perempuan), there were 1,721 complaints of cyber gender-based violence cases in 2021, which is a staggering increase of 83 percent from 2020.

Meanwhile, AWAS KBGO – an advocacy group for cyber gender-based violence and an offshoot of a digital rights protection group called the Southeast Asia Freedom of Expression Network (SAFENet) – reported 677 complaints, 559 of which were from women, in 2021. The Legal Aid Foundation of the Indonesian Women’s Association for Justice (LBH APIK) reported 489 cyber gender-based violence cases, which is the highest number among all types of sexual violence cases, in 2021.

Komnas Perempuan’s Veryanto Sitohang said victims are generally reluctant to file complaints as they fear it could open them up to intimidation, extortion and exploitation.

“Considering the increasing number of cyber gender-based violence cases, protection and rehabilitation of the victims is urgent, [and this can be helped with] the passing of the anti-sexual violence bill,” he said.

Veryanto was referring to the Sexual Crimes Bill (RUU TPKS), which had been in parliamentary limbo for 10 years due to constant resistance from conservative groups who wrongly argued that it would promote promiscuity and liberal sex values.

After years of struggle and modifications to the bill, RUU TPKS was finally passed into law on April 12, 2022. With it, Indonesia can now can offer victims greater legal protection from, and enforce harsher punishments against, sexual violence perpetrators in Indonesia.

Thanks to the new law, cyber gender-based violence is now unambiguously categorized as a type of crime. It specifically defines the taking and/or spreading of intimate images without consent as a crime punishable by up to four years in prison. Victims are now legally entitled to legal representation and psychological counseling, as well as compensation for material and immaterial damages.

On its own, the Sex Crimes Law (UU TPKS) represents a firm step towards reducing sexual violence. Yet it remains to be seen how it will interact with two other controversial Indonesian laws: the Electronic Information and Transaction ACT (UU ITE) and the Pornography Law. Both laws are considered to be ambiguously-worded and have been used, time and time again, to criminalize victims instead of perpetrators.

“The interesting thing is that abusers can use [the law] to criminalize cyber-based gender violence victims, especially regarding non-consensual distribution of intimate images,” Ellen Kusuma, who heads the online gender-based violence division at SAFENet, explained.

Put simply, she said abusers can use UU ITE – which criminalizes any online communication that could be considered defamatory to a particular party – to hit back and sue their victims when a case goes public and ruins their reputation.

In regards to pornography, its very definition is still blurry under the Pornography Law. Based on its wording, the creation of intimate content that is produced for private consumption, but gets leaked to the public, can be considered grounds for prosecution in Indonesia.

“When law enforcement thinks everything that contains nudity [is porn] and doesn’t see the larger picture, statutes under the Pornography Law could be used to criminalize victims,” Ellen explained.

As such, victims are often presented with a narrow window in which they can file a report with the police.

“A concerning perspective also comes from the police, wherein victims [who don’t] directly report their cases can potentially be prosecuted. For example, when someone becomes a victim of non-consensual distribution of their intimate images, and the victim didn’t report [the incident to the police], the victim could be reported by someone else and she or he could become a suspect,” Ellen said.

And then there is a long-standing lack of trust in the police due to a lack of sensitivity in handling sexual violence cases and a pervasive culture of victim-blaming. “This is obvious as, in cases of non-consensual distribution of intimate images, they must hand over pieces of evidence that makes them vulnerable to male police officers,” she added.

A famous recent example involves a West Java woman, named VN, whose private sex tape with her ex-husband and other men leaked to the public. It’s unknown who leaked the video, yet she was sentenced to three years in prison and slapped with an IDR1 billion (US$69,681) fine under the Pornography Law in 2020. While the men in the case were also convicted, most public scrutiny was aimed at VN.

Platform failures

Combating cyber gender-based violence requires a two-pronged approach: law enforcement and getting the social media platforms to act.

In the case of Twitter, many abusers have been able to skirt content moderation rules due to the ease of creating and maintaining backup accounts.

As SAFENet has experienced in their handling of these cases, shutting down abusers requires much more work than simply filing reports using the platform’s in-app features.

Ellen said that it is much easier to create a new account rather than report a violation, presenting a loophole for abusers to exploit.

“So people who want to create a new account do not need to verify their identification, but people who want to report [by filling a report form] need to do so,” she said.

“Digital platforms should address the non-consensual distribution of intimate images. Why do the platforms need to verify the identity [of the victims], since we know this happens time and time again to the victims?”

Regarding Twitter’s non-consensual nudity policy, the platform states, “Sharing explicit sexual images or videos of someone online without their consent is a severe violation of their privacy and the Twitter Rules. Sometimes referred to as revenge porn, this content poses serious safety and security risks for people affected and can lead to physical, emotional, and financial hardship.”

The policy was last updated in November 2019.

“Fuck you. Fucking burn. I hope that the women in their lives can get out. I hope that their mothers, wives, children, daughter, sisters truly realize what fucking pieces of trash they are and kick them out.”

Arnia

Twitter offers several examples of the types of content that violate this policy, such as “hidden camera content featuring nudity, partial nudity, and/or sexual acts; creepshots or upskirts – images or videos taken of people’s buttocks, up an individual’s skirt/dress or other clothes that allows people to see the person’s genitals, buttocks, or breasts; images or videos that superimpose or otherwise digitally manipulate an individual’s face onto another person’s nude body; images or videos that are taken in an intimate setting and not intended for public distribution; and offering a bounty or financial reward in exchange for intimate images or videos.”

In our investigation, we found that much of the content created by the trolls targeting Chinese-Indonesian women fit the above descriptions. However, we also found many cases in which the abuse came in text form. Twitter’s policy only covers violations related to images and videos, not text.

But Twitter offers space for anyone to report “content where a bounty or financial reward is offered in exchange for non-consensual nudity media,” as well as “intimate images or videos that are accompanied by: text that wishes/hopes for harm to come to those depicted or otherwise refers to revenge, e.g., ‘I hope you get what you deserve when people see this’; and information that could be used to contact those depicted, e.g., ‘You can tell my ex what you think by calling them on 1234567’.”

Our investigation did not discover any content that contained the contact number of the victims. We found plenty of tweets containing language that contained intent to harm or rape, but did not explicitly refer to revenge. In many of the cases we looked at, it’s difficult to argue that they fall under the category of revenge porn in that they lack the element of personal ill-will towards the victims.

We have approached a Twitter representative in Southeast Asia for clarification but have not received a response.

If Twitter finds any instances of non-consensual sharing of intimate images, they can immediately and permanently suspend the account responsible, as the policy outlines.

However, Twitter also states, “In other cases, we may not suspend an account immediately. This is because some people share this content inadvertently, to express shock, disbelief or to denounce this practice. In these cases, we will require you to remove this content. We will also temporarily lock you out of your account before you can Tweet again. If you violate this policy again after your first warning, your account will be permanently suspended. If you believe that your account was suspended in error, you can submit an appeal.”

As our investigation shows, many abusers can hide their identity, create backup accounts, create new accounts, change their usernames, and even create impostor accounts. Of the thousands of accounts that we tracked, only a handful were ever suspended at any point.

Thousands of women have fallen victim to these predators’ sexual abuse, yet some of them might not even be aware of it.

On April 7, 2022, we found @aesshinn again, but this time his account was set to private after he changed his profile picture and account details. All the victims’ efforts to report his account seemed futile.

Arnia hopes that one day she can confront her online abusers, who cowardly hide behind their online aliases, face-to-face. She said she would love to post photos of their faces along with their penises on her Instagram and see how they like it.

Anger swells whenever she looks back at the abuse she has endured. To her harassers, she says, “Fuck you. Fucking burn. I hope that the women in their lives can get out. I hope that their mothers, wives, children, daughter, sisters truly realize what fucking pieces of trash they are and kick them out.”

*Arnia’s real name, as well as certain details about her life, have been omitted, at her request, to protect her identity.

If you are a victim of cyber-based gender violence or sexual violence, here is a list of organizations that you can contact for help. AWAS KBGO (Beware of Cyber-gender Based Violence), an initiative to tackle cyber-based gender violence by the Southeast Asia Freedom of Expression Network (SAFENet), offers free digital privacy consultation services and a handbook to understand the non-consensual distribution of intimate images.

Kevin Ng can be reached through his Twitter @sandhatu for tips or for anyone who wants to share their stories regarding this case.

This story has been translated to Bahasa Indonesia. You can read that version here.