There are two groups of people allowed to access the road to Serangan’s Pantai Dua and Pantai Tiga beaches — Balinese going to pray at the holy Sakenan Hindu temple and construction workers.

It wasn’t always this way. Once a paradise for surfers in the wet season, the reclaimed island south of Denpasar — Bali’s capital — has seen bulldozers and cranes take the place of the humble food stalls, or warungs, that once served local fare like fried rice and coconuts to surfers and beach-goers.

Change came last April. It came fast.

In the first week of that month, a circular warned vendors on the two beaches that they had just one week to vacate the premises ahead of a planned April 16 demolition. The beach, developers told them, was being cleared for the highly-anticipated October 2018 IMF-World Bank meeting, though the government has never publicly connected the two.

The sudden transformation of the landscape has been a loss for surfers who had long gravitated towards what was once a hidden spot in the off-season, when winds favor eastern-facing breaks. Not only were the waves good, with anything from mellow rides to intense peaks, but the beach was a favorite for its chilled-out atmosphere.

“I really loved hanging out at Serangan, especially in the rainy season. Serangan became more famous over the last few years, but it still had this quiet, isolated charm,” Elisa, a German surfer told Coconuts Bali.

“My favorite warung, with the nicest owner, was Pak Lila. He always served me fresh fish and the best nasi goreng.

“The beach, the vibe, and the surf are amazing in this little half island.”

While the scene described by the German no longer exists, rumors that the break is completely shut off to surfers are unfounded, according to local residents, who have told Coconuts Bali the surf can still be accessed by hired boat.

But while surfers with enough money can still access their favorite breaks, the real losers in this situation are the locals who built their lives on those beaches. Locals like Ibu Dedik.

The owner of a warung for 15 years, Dedik sold Indonesian food and provided a cozy spot for surfers to hang out before or after a paddle out, her life has since been turned upside down by the development. Her restaurant gone, she now peddles plastic phone case lanyards.

While the warung owners had their businesses for years and paid for their own structures and improvements, they were renters, a harsh reality that made it easy for them to be swept aside when the time came. None were offered compensation for their trouble, Dedik told us.

“We built that warung. We spent IDR35 million (US$2,420) building it,” she told Coconuts Bali as she approached tourists with her lanyards.

In the past three months, Dedik has done her best to establish a new routine as she tries to eek out a livelihood. The 47-year-old makes an early start each day, making her way to a nearby pier at 7am to catch her potential customers, tourists, who are predominantly East Asian, as they get dropped off for the fast boat to Nusa Lembongan. Sales haven’t been encouraging.

Dedik is joined by other familiar faces from the bulldozed space, like her sister, part of a de facto co-op of women who refer to themselves as the “old ladies.”

They, like her, once ran warungs or gave massages to tourists on the beach and are now selling phone cases because they just don’t know where to go from here.

“What else can I do? I’m already old,” the mother of three told us through a mix of smiles and tears.

You’ve heard the term “resting bitch face”? Dedik has “resting smile face.” As we talked to her, she would always try to smile, but eventually had to look away and sob when we asked about her prospects.

“It’s hard to find a job. The money from this isn’t enough to live, but what else can I do?

“My husband is also working, but we don’t make enough,” she said.

Much as you find all the fabric shops in one part of town or all the plant nurseries on one road in Indonesia, the sense of camaraderie is strong with the women. Yes, they are de facto competitors, but they all source their lanyards from the same place and try to make sure sales are spread around.

Dedik and the team stop their hawking by 11am, as the sun fully kicks up and interest in her wares begins to decline in inverse proportion to the sweltering heat.

When asked about her long-range gameplan given that selling lanyards isn’t enough to put food on the table or pay for her kids’ school, Dedik told us simply, “I don’t know.”

An ‘Island of Happiness’

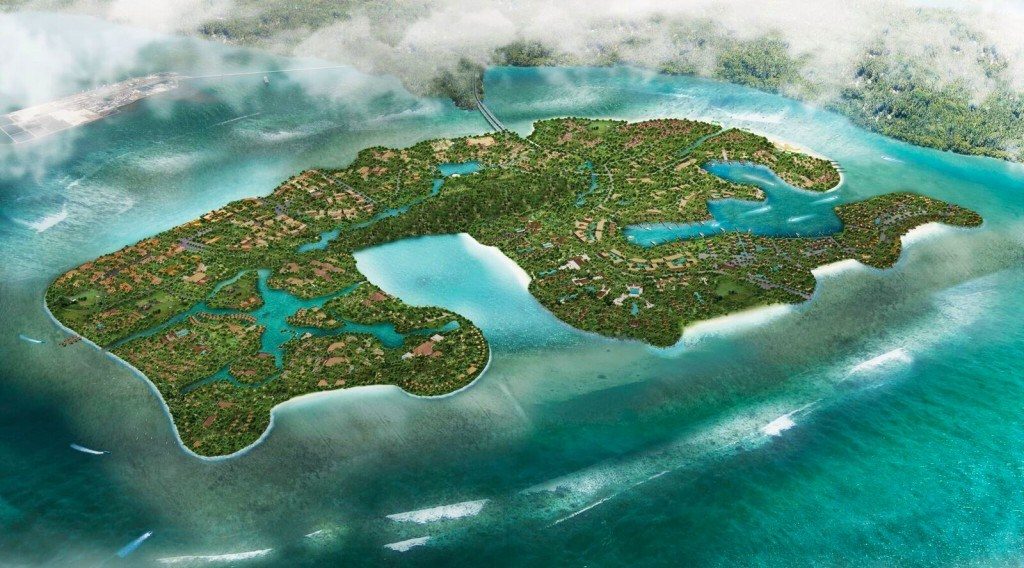

Although the plans for the beach has been reported in local media as a beach club, what appears on the website of Singaporean developer the Giti Group is much bigger than just Pantai Dua and Tiga. Encompassing the entire island, it’s ironically called the “Island of Happiness.”

The project, dubbed “Kura Kura Bali, is “guided by the Balinese way of life,” the website says, citing the Balinese philosophy Tri Hita Karana to “protect the island’s natural resources and minimize its impact on the environment, while creating incredible opportunities for people to experience the island’s natural and cultural heritage.”

The mockup on the website shows a Dubai-esque vision of a commercial utopia complete with a luxury eco-lodge full of villas, an opera house(!), and tram system that looks nothing like the Bali we know, and a bit more like, well … Singapore.

The website claims that Serangan Village on the northern part of the island, a town inhabited by more than 3,800 Balinese, will remain “integrated.” But given the way the warungs at the beach were handled, you have to wonder if claims of valuing the local community are much more than window dressing.

Doomed to repeat history?

Coconuts Bali‘s inquiries to Kura Kura Bali about the status of the development have received no reply, but the project design feels familiar to those who have lived in Bali long enough.

The island was the site of South Bali’s first reclamation project in 1998. It left us with something of a wasteland, wreaking havoc on the environment’s coral, mangroves, and turtle population. The touted vision was that of a booming hot spot of hotels, a fresh new dynamic tourist destination.

It looked pretty amazing in the sketches; what we got was an entirely different story.

If there’s any lesson we can learn from the past, it’s that these projects often run out of money, encounter corruption, fall desperately short of the conceptualizations, and all-too-often harm the environment. In this case, you can add in the harm being done to a local Indonesian population that had lived on the land for decades.

Correction: An earlier version of this story misspelled Sakenan. The story has now been fixed, thanks to a reader for pointing out the mistake.

Reader Interactions