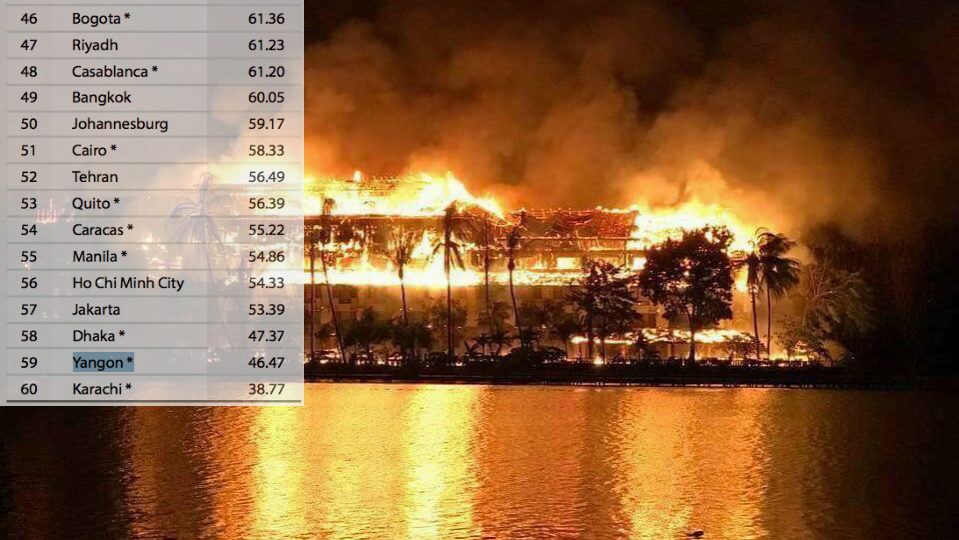

Back in October, we first summarized Yangon’s placement in the Safe Cities Index 2017 with an article titled “Yangon ranked second most unsafe city in the world.” We received a lot of frustrated feedback from readers who live in or have visited Yangon, most of whom professed they have never personally felt unsafe in this city.

It was obvious then that most of these people did not read the Safe Cities Index, and it’s pretty obvious now that neither did the author of an article in the travel section of yesterday’s New York Times or her main interlocutor.

The article by Shivani Vora, titled “Five Destinations That Call for Caution,” lists five of the eight worst-ranked cities in the Safe Cities Index (not the bottom five, for some reason) and tries to explain why they are so unsafe. Yangon is one of those cities, but the reasons Vora cites to explain why Yangon is so dangerous are nowhere to be found in the index itself.

According to Vora’s main source, an associate managing director for a security consulting company named Greg Boles, Yangon is unsafe because of Muslim-Buddhist tensions.

“The fighting between the two ethnic groups can be violent and unpredictable,” he tells Vora. “From a tourist perspective, it’s an unstable city because you don’t know what’s going to happen next.”

The Safe Cities Index, produced by the Economist Intelligence Unit, does not contain the words “Muslim” or “Buddhist,” and though there are certainly inequalities in the city, Yangon has rarely been the site of major intergroup conflict.

Furthermore, what Vora and Boles call “tensions” do exist elsewhere in the country, but they would be more accurately described as “genocide,” according to UN experts. International tourists, not to mention international rights investigators, cannot get anywhere near the violence.

The real reason Yangon is ranked as the only city safer than Karachi is because it scores poorly in four key areas: digital security, health security, infrastructure security, and personal security.

In other words, Yangon’s five million residents are vulnerable to cyber threats, infectious diseases, poor health services, poor governance, shoddy infrastructure, fires, natural disasters, and traffic accidents.

(Anyone who feels safe in Yangon probably didn’t read the index and/or enjoys the privilege of not having to worry about these systemic, structural dangers, which kill people every day.)

By ignoring the contents of the index, Vora and Boles failed to realize that it has little useful information for tourists and has no place being cited in the travel section of the newspaper. The word “travel” does not appear anywhere in the index. Being cautious while visiting Yangon will not make the hospitals better or the government less corrupt or the buildings less flammable.

The Safe Cities Index offers a view of the world’s cities from the perspective of the thousands who are most vulnerable to gaps in services. In trying to appropriate the index to advise international tourists on how to enjoy their holidays, Vora and Boles seem to have lost sight of its true purpose, and they ultimately produce a portrait of Yangon that ignores its real problems and reduce Myanmar’s greatest crime to a lazy, orientalist spectacle.

Reader Interactions