“I recently gave a new staff member an order that came from a real table of customers. I was watching what he did. When he pulled the tea, he only pulled it once for the first cup and transferred it to the cup, but he pulled the other cups for a longer amount of time. I took that first cup and told him to make another one, making sure he pulled it two or three times,” Rangoon Tea House’s head mixologist Aung Zin Moe recalls of a recent test that he gave a new staff member.

“After completing the order, I took the first cup that he made and I let him drink it, and I drank it myself. The condensed milk hadn’t melted because he’d only pulled it once. Condensed milk is thick, and the taste of the milk was separate from the rest of the tea. When I let him drink it, he saw that the lingering flavor wasn’t that of the tea leaves, but the sweetness of the condensed milk.”

Although daunting, that’s the kind of test that Aung Zin Moe gives to all new bar staff. It’s also that level of precision when it comes to la phet yay that put RTH on a recent CNN list of “the world’s best tea houses.”

“That was a memorable day,” he tells me of when he found out the news. “Of course I wanted to accomplish something like that from the beginning, but I didn’t think it would happen. Now that it has, I’m very happy. I want the restaurant to expand and be more successful and really get to highlight la phet yay.”

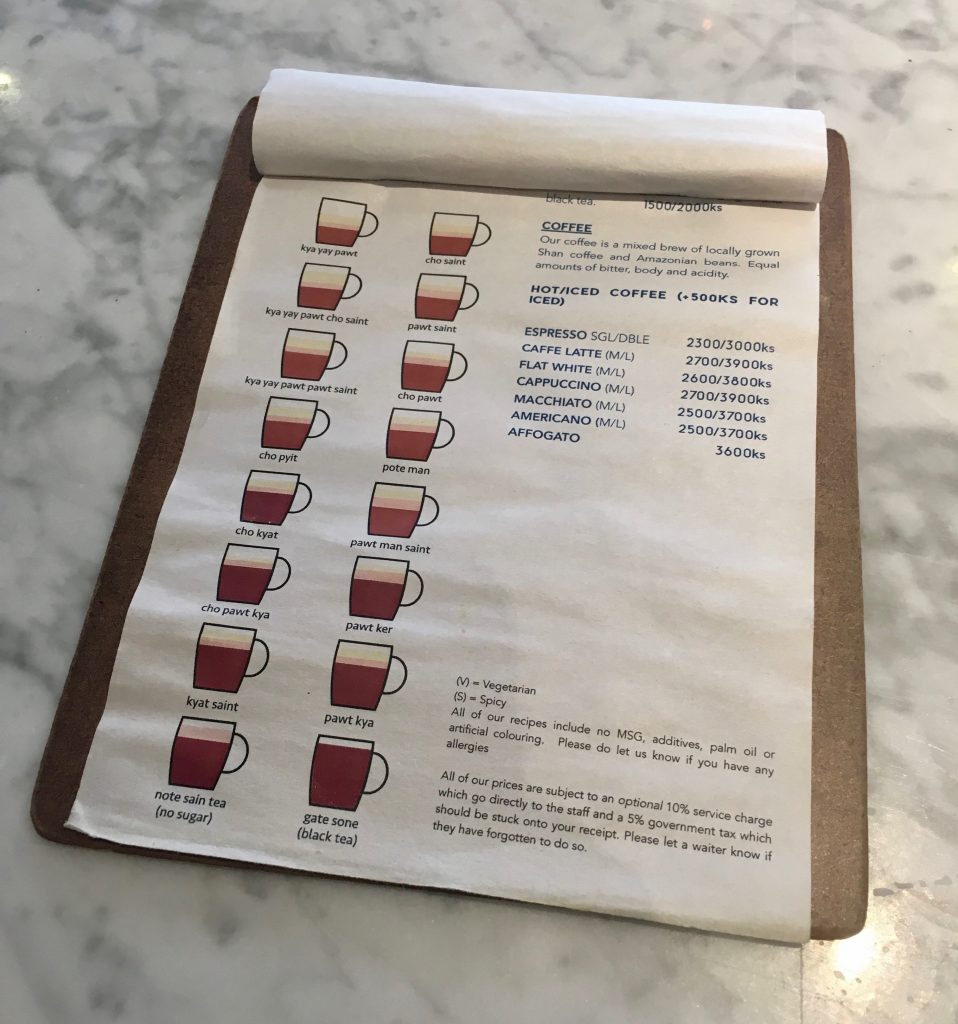

After all, in spite of all the other accomplishments that it can tout, RTH is, at its core, a tea house. Currently, the restaurant has 16 different brews of la phet yay on offer, each recipe put together by Aung Zin Moe himself.

Before RTH, Aung Zin Moe had been making tea for about eight years. Although he didn’t start off as a tea maker in the tea shops he worked at, he quickly became interested in the topic, asking those in charge of the tea to take him under their wing. He even opened up his own tea shop in Nyaung Lay Pin at one point, but eventually moved to Yangon to look after his ailing father.

After a series of chance encounters, Aung Zin Moe landed an interview with Htet Myet Oo, one of the co-founders of RTH. “My cousin brother got in touch with [Htet Myet Oo] and told me, ‘He wants to open a restaurant. He used to live in England, and just moved to Yangon. He wants to elevate Myanmar food and make it the best it can be,’” Aung Zin Moe recalls.

“When [Ko Htet Myet Oo] told me about his plans, you know, I felt encouraged because it was what I wanted too. When it comes to tea, a lot of people here think ‘Oh, it’s just a tea shop.’ But when you have someone who motivates you, it makes a difference and I’m really thankful.” Aung Zin Moe got the job.

However, despite his passion and belief in the vision behind RTH, he admits that he too was initially hesitant about the restaurant’s high price point — one of the biggest criticisms that the business has drawn.

“I was worried,” Aung Zin Moe laughs. “When I worked in other tea shops, including in Yangon, the most we charged was 500 or 700 kyats. When Ko Htet Myet Oo said that one cup of tea here would cost 1500 kyats, I immediately felt that that was a lot. But I had faith in myself and although I was a bit startled by the price, I believed that our taste was different from others’. It worked out in the end, but I was definitely worried in the beginning.”

Preparing the ingredients

In order to ensure that the quality of their la phet yay matches its price, Aung Zin Moe goes to great lengths to guarantee that each cup is consistently excellent.

“Tea is different from one shop to another. When I got here, I tried experimenting with a new formula,” he explains. Just like bakers consider their craft a science, Aung Zin Moe approaches the different components of a cup of la phet yay — the main ones are the tea leaves, the condensed milk, and the evaporated milk, he tells me — in a methodical manner.

First off, regardless of how experienced you are, a cup of la phet yay is only as good as the tea leaves used to brew it. The leaves from RTH are ordered directly from Shan State and contain no pesticides, and Aung Zin Moe regularly examines them to verify that they’re of a certain caliber.

“Sometimes when the weather changes, so do the tea leaves,” he tells me. “When this happens, I’ll notice it as I’m brewing and I’ll send them back and tell [the company] that these are different from the tea leaves I normally use.”

As to how he can tell whether or not a batch of leaves is good, he explains, “First, I look at the leaves, and if it looks similar to the ones I usually use, I brew them. Once you pour in hot water and it starts simmering, the difference becomes clear. If you were going to just let it brew all day, then the difference wouldn’t be that noticeable and it would only be the flavor that would change. But because we put it in a steel mug [for each individual cup], as soon as we put in the hot water, if the leaves aren’t good, the odor smells off and the final product isn’t what we want.”

Even the condensed milk that they use has to pass Aung Zin Moe’s strict standards. He’ll try out new brands who provide him with samples, but he’s meticulous about which ones to actually use on a daily basis. “If it’s not working for me, I don’t use it because first of all, the price that we’re charging is important. Second, I don’t want to give customers tea that doesn’t taste good. If the condensed and evaporated milk [brands] are changed, the whole taste is altered.”

How to make la phet yay

“The main thing is that right after the water’s boiled and it’s piping hot, we put a specified amount of grams of tea leaves in it, and it’s brewed in a specific container. It’s extremely important when the leaves are brewing — that’s the main part of la phet yay,” Aung Zin Moe answers when I ask him what the most crucial step is. “Some people who don’t understand tea leaves don’t know how to capture the scent of the leaves and the tea smells ‘raw.’ We get rid of that raw smell and capture its fragrance.”

Each new bar staff at RTH is given a list of all the brews and their recipes, down to the specific grams of each ingredient that goes into a brew. After a few weeks, they’re given a sample test order. While Aung Zin Moe understands that it’s difficult for new employees to remember every step of the procedure, he doesn’t back down from the standards that RTH has set. And because they make each cup of tea to order instead of in large batches, consistency is just as crucial as quality.

Even the amount of hot water that goes into each cup is critical, as is the height at which the hot water is poured. He explains: “[Pouring the water] captures the fragrance and sweetness of the tea leaves within minutes, so the water can’t be cold. Pouring the water from a higher height isn’t the same as pouring it lower and directly into the cup; the oil from the leaves won’t rise properly [if you pour it from up high], and the consistency becomes thin, and that’s when that raw smell comes out.”

“The cups themselves are also important,” he goes on. “Sometimes I go and drink at other tea shops for research, and I see a lot of the time that there are drops of tea on the side of the cup; that gives the impression that the tea was poured haphazardly. When the hot tea dries up, it leaves behind rings. When I see that on the cup, it affects my own opinion of the tea, and I don’t want my customers to feel that way either.”

La phet yay at RTH is also ‘pulled’ between two cups — a practice that not many tea shops practice today. While it requires a bit more time, Aung Zin Moe finds that pulling a cup “at least three times” contributes to the final flavor. “The difference is that when you pull the tea, the air creates foam, so when it arrives in front of the customer, it’s not too hot or too cold.” For staff who have never pulled tea before, Aung Zin Moe gives them two steel cups and a bit of dishwashing liquid with which they can practice until the number and length of their pull are just right.

And while speed is important, so is strategy, especially when several different brews have been requested. “Some orders have four or five cups, and while we’re pulling one cup, the foam in the other one falls,” he explains. “So if for instance we have one cho saint, one kyat saint, and pote man, we have to think about it first. All the cups have to be pulled, but between the three, we pull the cho saint first; this is because cho saint has sweetness and is thicker, so the foam doesn’t fall as easily. Then we can pull the other ones, and there’s still an equal amount of foam in all the cups at the end.”

All of these details might sound complicated, and they are, but Aung Zin Moe refuses to settle for anything less. “Regardless of how important the order is, even if the customer is complaining because it’s taking too long, I don’t accept a cup of tea that’s carelessly made and is just put out for the sake of having it completed,” he tells me in a resolute tone. “Regardless of how much we have to apologize to the customer, the tea that we give them should be of the standard that we’ve set.”

Towards the end of our interview, I ask him what his favorite brew is. “It’s not on the menu right now,” he smiles, as though he’s deciding for a split second whether or not to keep it a secret. “The staff at my last job kept experimenting, but it never turned out the same. They asked me [how to make it] but I didn’t tell them. When you drink it, there’s a taste that lingers behind; the taste isn’t condensed milk, it’s a particular taste of la phet yay. When they asked me what this brew was called, I said it was ‘shar swe’ [‘lingers on the tongue’].”

Whether or not Aung Zin Moe will ever debut ‘shar swe’ on the official RTH menu is at his discretion. But with the pride and care that he puts into his work, every cup of la phet yay that Aung Zin Moe makes becomes a form of shar swe.

Reader Interactions