In the past year, a single company has come to be understood as powerful enough to facilitate Russian interference in an American presidential election, ensure the integrity of Germany’s parliamentary election, and potentially cripple opposition to Cambodia’s authoritarian leader.

Facebook, no longer just a tech company, has become a primary source of information for a quarter of the world’s population. But unlike news distribution systems that came before, Facebook treats almost all information equally, allowing falsehoods and incitement to thrive and, at times, inspire its users’ actions.

This week, another weight was hung from the company’s neck, with the New York Times pinning at least some of the blame for Myanmar’s violence against the Rohingya Muslim minority on the shortcomings of Facebook’s approach to ensuring that the country’s 30 million users are practicing mass communication peacefully.

This approach, according to Facebook spokesperson Clare Wareing, includes filtering out direct incitement, promoting media literacy, and encouraging users to report dangerous content.

“We allow people to use Facebook to challenge ideas and raise awareness about important issues, but we will remove content that violates our Community Standards,” Wareing told Coconuts. “In Myanmar, we have been working with local communities and non-profits to tackle hate speech and raise awareness of our policies for several years… We are also working to help promote news literacy and recently ran a series of public service ads, developed with the News Literacy Project, to help inform people on Facebook about this important issue.”

The company also released a series of Myanmar-language resources to educate users on the dangers of bullying, hate speech, and violent threats.

Unfortunately, these safety mechanisms still leave the bulk of the responsibility for correcting misinformation and reporting violence in the hands of users, and few people in Myanmar have taken up this responsibility on behalf of the Rohingya.

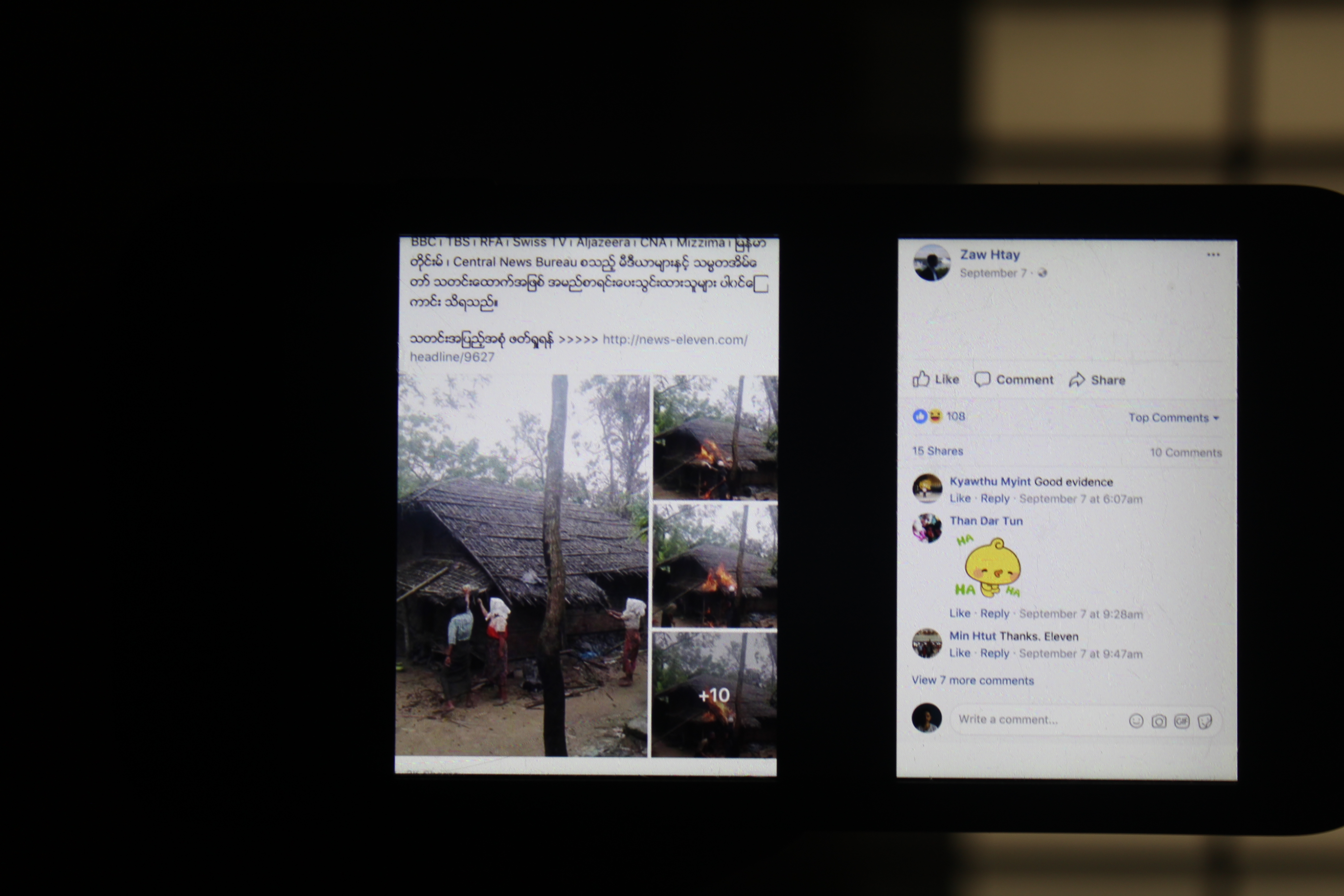

Promoting standards and literacy have done little to stop Myanmar netizens, including State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi, her spokesman Zaw Htay, and Commander-in-Chief Min Aung Hlaing, from using Facebook to spread misinformation and vitriol about the Rohingya as a people to audiences of millions.

So, does Facebook’s usefulness to Myanmar’s leaders mean the company is to blame for its clients’ violence against the Rohingya? Human rights advocates say: “Not exactly.” Does the company have a role to play in ending the violence? “Absolutely.”

“The entry of Facebook into Myanmar, coming after literally decades of military censorship and severe restrictions on freedom of expression, has been a double-edged sword,” said Phil Robertson, deputy Asia director for Human Rights Watch. “The positive side is people can speak their minds, corruption and rights abuses are exposed quicker, and information about daily events inside and outside of Myanmar can go straight to users, bypassing filters and controls, presumably resulting in a better-informed citizenry.

“The problem is that Facebook has also become hi-jacked by some for use as platform for spreading ethnic and religious stereotypes, stoking hatreds, and instigating violence – and this is where Facebook is falling down, by failing to do the levels of hands-on monitoring they need to do. Facebook can’t be an absentee landlord when some of the denizens have gas and a match and are prepared to burn the place down.”

Rohingya activist Nay San Lwin offered another distinction.

“Violence against Rohingya is national policy in Myanmar, so I don’t want to blame Facebook,” he said. “But Facebook is responsible for allowing the spread of hatred against the Rohingya community. They never take down any hateful posts by Burmese Buddhists, even though many users report them. Facebook removed many posts advocating for peace and news updates on what’s actually happening on the ground.

“In my opinion, Facebook doesn’t have a policy to side with anti-Rohingya users, but the team responsible for Myanmar is completely biased and against the Rohingya community. Facebook headquarters should conduct proper investigation.”

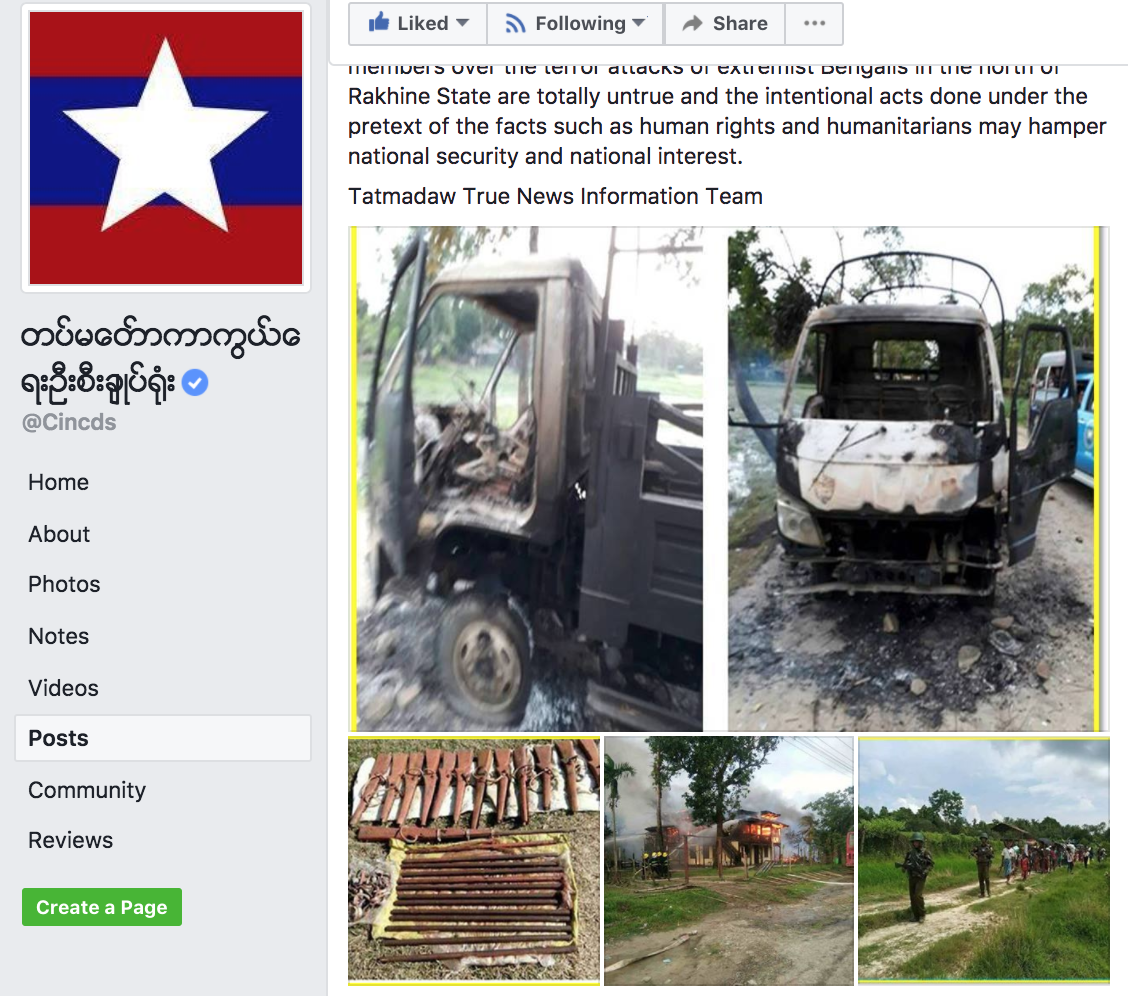

Fortify Rights CEO Matthew Smith echoed this distinction: “We’ve documented a coordinated, systematic Myanmar Army-led attacks on Rohingya civilians. We wouldn’t say Facebook bears direct responsibility for that, or even for the behavior of civilian perpetrators in Rakhine who participated in massacres in recent weeks.

“But the company has a role to play. The views of people throughout the country have been shaped by what they’ve seen and read on Facebook, and there’s a lot of misinformation. Even government departments and officials have used Facebook to stir anti-Rohingya sentiment rather than instill calm. Hate speech thrives on Facebook throughout the country, and that shapes some people’s views in very ugly ways. Incitement is a crime, and Facebook has arguably been a platform for it.”

He added: “Anti-Rohingya sentiment, fear-inspiring rumors about Muslims, and other misinformation spreads on Facebook as fast as fires in Rakhine. Facebook alone can’t prevent that, but the company certainly has responsibilities in the Myanmar context.”

To Burma Campaign UK director Mark Farmaner, this “No, but…” response to the question of Facebook’s blame in anti-Rohingya violence is a distraction from where he says the blame truly lies – with the Myanmar government and military.

“It is utter nonsense to suggest violence against the Rohingya has been fueled by Facebook posts,” he said. “What is happening to the Rohingya is a deliberate and systematic military-led operation to drive the Rohingya out of the country. This is being done by the State and a well-armed military force, not by racists posting cartoons on social media.

“To borrow a phrase from Aung San Suu Kyi, the hate speech we see on social media might be most easily visible, but it is just the tip of the iceberg. For example, the attacks against Rohingya in 2012 were incited by more than a year’s worth of on-the-ground agitating and organizing by local politicians, with the cooperation of the State,” he said.

Anti-Muslim monk Wirathu and the anti-Muslim 969 and Ma Ba Tha movements, which were blamed for much of the communal violence between Muslims and Buddhists in 2012 and 2013, Farmaner said, “mostly operated on the ground, distributing leaflets and DVDs, making sermons, and were facilitated by the State, which used them for its own political agenda.”

“Undoubtedly, Facebook should be taking much more action against hate speech and incitement of violence against the Rohingya and all Muslims in Burma,” he said. “But it can’t be blamed for the current violence.”

Jamila Hanan, a human rights activist whose #AllRohingyaNow movement has lobbied Unilever, Telenor, and Nestlé to take public stances against human rights abuses, says Facebook should be treated no differently.

“Everyone has a duty to take a stand against genocide, especially corporations, including Facebook,” she said.

“Clearly, in the case of the Rohingya genocide, Facebook have failed in their corporate responsibility to use their position of power to help stop these ongoing atrocities, and worse than that, they have allowed their space to be used to spread hate propaganda and appear to side with the Myanmar regime through the silencing of activists.

“No corporation should be associated with genocide, all should be condemning it, and those that have a relationship with Myanmar should be looking at what they can proactively do to help stop this ongoing ethnic cleansing.”