While the holy month of Ramadan is one of fasting, prayer and reflection for many Muslims, it is also a time of inconvenience to some, especially those who choose not to fast, like 28-year-old Kwan, who was once caught eating in public.

It so happened to be the day he forgot to bring his identity card along. “As I do not look completely Malay, I pulled out my best Sabahan accent and tried to convince the authorities that I was not a Muslim. Somehow, it worked and I was let go without any other incidents,” the event executive told Coconuts in an interview.

In Malaysia, it’s easy for the authorities to distinguish between Muslims and non-Muslims with just one glance at a person’s identity card. A Muslim would usually have “bin” or “binti” written on the card, which translates to “son of” or “daughter of,” respectively. Those born to at least one Muslim parent are automatically regarded as a Muslim.

Kwan started questioning and losing faith in the religion around the age of 12 after his religious teachers told him things he just couldn’t accept, like saying that non-Muslims would be condemned to hell. He eventually stopped believing in the practice and began to feign health issues during his teenage years so he could abstain from fasting. When friends got nosy, Kwan, who was visibly overweight, would simply say that he had diabetes and could not go for long periods without sugar or water.

“After all, who would question an overweight person saying they have diabetes?” he asked.

Fellow Muslim Ziggy started questioning the purpose of fasting at the tender age of 12.

“I was told that I needed to fast to feel how the poor live without food,” he said.

“I absolutely can’t relate to that because I am not poor and have a lot of food in my house. I don’t need to fast to have empathy and sympathy for the poor,” the 27-year-old added.

In a country renowned for its hearty cuisine, Malaysia is also infamous for its religious-policing, usually done by state-appointed authorities like the Selangor Islamic Religious Department or JAIS.

Muslims who do not fast can be fined up to RM 1,000 (US$250) each and jailed for up to six months. Even for those who have been spared from fasting due to physical ailments or menstruation, they cannot eat in public. F&B operators also face fines for serving Muslim customers.

While the country’s rich diversity helps those with racially ambiguous features to blend in, those who have unmistakably Malay features are a little more fearful.

Prior to the pandemic, videographer Izzy, 28, frequented non-halal establishments during the fasting month. But he now fears that the authorities may find out his whereabouts using the MySejahtera coronavirus tracking app if he was ever caught eating in public during the holy month. Outside of Ramadan, there is no law that prohibits Muslims from patronizing non-halal establishments.

“I usually go to non-halal restaurants but the pandemic has made me change my ways,” he said. “I get too scared at times to check in there so I would have some of my colleagues bring me food if they go out for lunch. If they order in, I’d piggyback on that as well. I’d sometimes bring food from home too, as it makes the hassle a lot easier.”

‘Liberal’ Muslims receive the cold shoulder

Muslims who practice their faith should observe the five pillars of Islam, according to preacher Abdul Rashid Abdullah from the Tun Abdul Aziz Mosque in Petaling Jaya, Selangor.

The five pillars are the declaration of faith, obligatory prayer, compulsory giving, fasting during Ramadan, and pilgrimage to Mecca.

“Take for example, a drop of water,” the ustaz said. “To those who are fasting, the first drop of water that breaks the fast is the most delicious.” When it comes to fasting, the person’s intentions remain of importance.

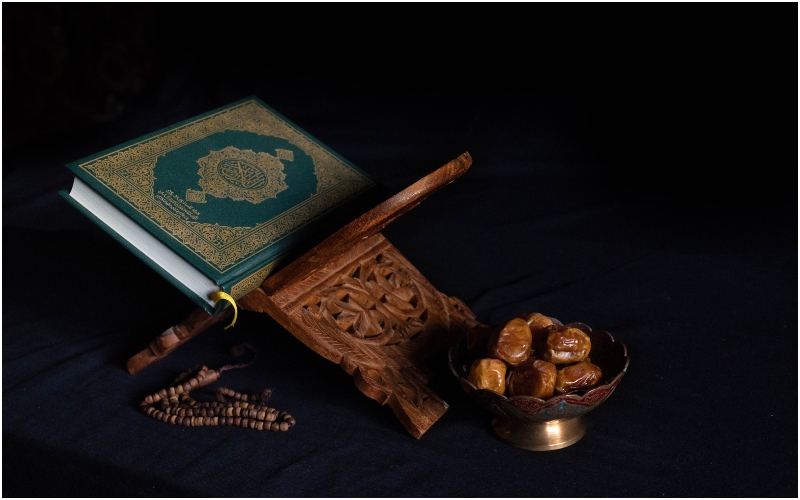

Fasting from dawn to sunset during the holy month is obligatory for healthy Muslims, who would rise early for pre-dawn meals and break fast with iftar that usually begins with water and dates. Muslims who are unable to fast during the month for reasons such as pregnancy or menstruation are encouraged to replace the days by fasting on other days of the year.

When less conservative Muslims try to question the various religious practices, some find themselves being treated coldly.

“A friend once told me I could ‘never understand because I don’t have faith’ when I asked her something regarding Islam that she couldn’t answer,” said Lyn, 35. She also described her holier-than-thou peers as “intrusive.”

“It’s Malaysia – people have been intrusive in every possible way. What I wear, where I eat, what I do. In general, how I publicly show how I do all the above,” she said.

Even in primary school, Kwan was ridiculed by his Muslim peers and religious teachers for wearing school shorts instead of long pants because exposing skin is perceived as sinful.

Izzy had relationships with partners who have threatened to break-up with him due to his non-conforming ways.

He said: “I don’t really pray a lot, and I smoke and indulge in other vices. I’ve been told off by JAWI (Wilayah Persekutuan Religious Department) before when I was out casually drinking in bars and I’ve had partners who would force me to stop drinking, eating pork, and smoking or they would break up with me.”

Despite these differences, however, the joy of Ramadan and the subsequent Aidilfitri celebration is not lost on them. While their lack of participation in certain practices of the religion does not see them celebrating Hari Raya Aidilfitri, or Eid, which marks the end of Ramadan, everyone is welcome to participate in the celebrations, which holds more of a cultural value rather than a religious one.

Other stories to check out:

Malaysian women denounce period spot checks in schools

Out and Proud: Fearless Malaysian defies hate with fabulous images of the LGBT community

Man opens up on struggle with religion, homosexuality, and coming out in Mecca