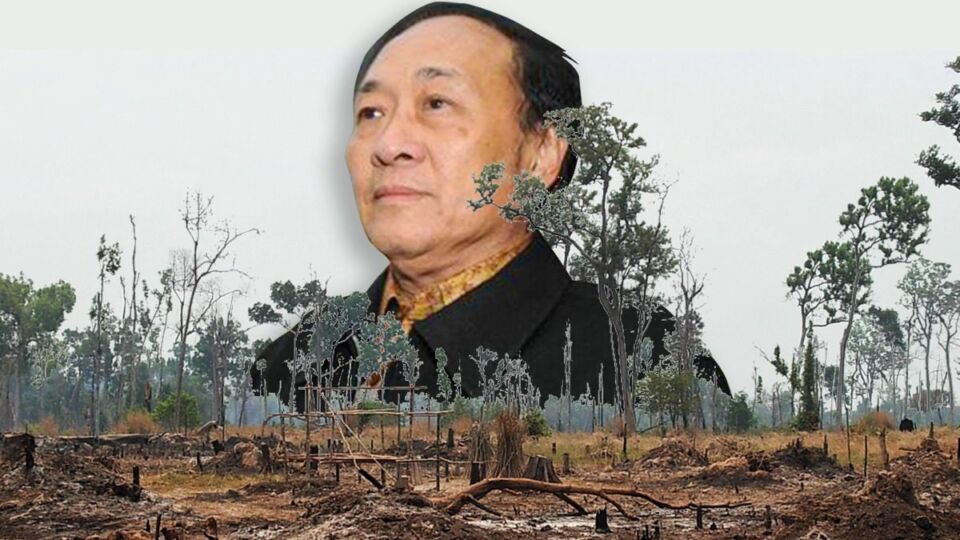

A court in Indonesia has sentenced palm oil billionaire Surya Darmadi to 15 years in prison for his role in the biggest corruption case in the country’s history.

The Jakarta Anti-Corruption Court ruled on Feb. 23 that Surya had conspired with the elected head of Indragiri Hulu district in Sumatra, Raja Thamsir Rachman, in 2004 to secure plantation permits for Surya’s company, PT Duta Palma. Surya was also found guilty on money laundering charges.

In addition, the court ordered Surya to pay 1 billion rupiah ($65,600) in fines and 2.23 trillion rupiah ($146 million) in restitution for the profit he reaped from the illegal plantations. The judges also ordered Surya to pay an additional 39.7 trillion rupiah ($2.6 billion) for losses incurred by the state.

Thamsir Rahman is currently on trial in the same case, and faces up to 10 years in prison if convicted.

There’s been a mixed response to the verdict in Surya’s case, in which prosecutors had sought a life sentence and total fines of 86.55 trillion rupiah ($5.7 billion). That’s the figure that prosecutors say represents the total loss to the state from the scheme, making it Indonesia’s costliest corruption case.

The Indonesian Forum for the Environment (Walhi), the country’s biggest green NGO, criticized the verdict as too lenient and not commensurate with the environmental damage that the illegal plantations had caused.

“The time it takes to recover the environmental damage caused by the activity of the illegal plantations is longer than the prison time,” Walhi forest and plantation campaign manager Uli Arta Siagian said.

She also pointed out that the illegal plantations had been in operation for 18 years, since 2004, meaning the sentence is also shorter than the age of the plantations.

However, Raynaldo Sembiring, executive director of the Indonesian Center for Environmental Law (ICEL), said the verdict should be appreciated as some measure of justice was done.

“This is probably the biggest state loss [from corruption] in the natural resource sector,” he told Mongabay.

Hendro Dewanto, the director of prosecution at the Attorney General’s Office, also welcomed the verdict, particularly the court’s order for Surya to pay for the state loss he had caused.

“The burden [to pay for the state loss] is put entirely on the defendant,” he said. “This is important to push for government efforts in improving the management of the palm oil industry.”

The billionaire who burned the forest

Under his 2004 deal with Thamsir Rahman, Surya received permits for five of his subsidiaries to establish oil palm plantations covering a total of 37,000 hectares (91,000 acres) of forest areas in Indragiri Hulu district — an area half the size of New York city.

Under Indonesian law, forests are off-limits for oil palm plantations. But this didn’t stop the forests from being cleared and oil palms from being cultivated. The palm oil from these plantations was reportedly exported to countries like India, Malaysia, the Netherlands, Kenya, Italy and Singapore.

The court found Surya profited from this illegal operation for nearly two decades, with the plantations generating monthly revenue of around 600 billion rupiah ($39 million). In 2016, he was ranked by local business publication Globe Asia as the 28th-richest individual in Indonesia, with a net worth of $1.45 billion.

But Surya’s rise came at great expense to others. The plantations left a trail of environmental and social destruction — disenfranchising Indigenous communities, damaging forest ecosystems, and causing losses to the state.

Environmental groups have long documented the abuses by Surya’s oil palm firms, including the illegal use of fire to clear land for planting.

Two of Surya’s companies operate on tropical peatlands, known for being one of Earth’s most efficient terrestrial carbon stores; hectare for hectare, they can store up to 20 times more carbon than tropical rainforests.

Legal permits for illegal plantations

In opting to hand down a more lenient sentence than prosecutors had sought, the judges cited what they called the mitigating factor that two of Surya’s companies had since acquired right-to-cultivate permits, known as HGU permits. These permits are the final set of licenses needed to be acquired by businesses to establish plantations.

This meant a hefty chunk of the claimed state losses could not be considered in the final verdict.

Prosecutors, however, pointed out that the process to acquire the HGU licenses is illegal. Bambang Hero Saharjo, a forestry lecturer at the Bogor Institute of Agriculture (IPB) who testified as an expert witness for the prosecution, said HGU licenses can only be issued after the companies acquire forest release permits. These permits, in turn, are needed to redesignate the land from forest area to non-forest, making it legal to establish an oil palm plantation there.

“So even though some [of Surya’s] companies had acquired HGU licenses, the status [of the land] is still forest areas,” Bambang Hero said as quoted by news outlet Betahita.

The judges, however, said that even though the process to acquire the HGU permits was illegal, the permits themselves remained valid as long as they weren’t revoked by the government.

Surya has decided to appeal the verdict. His lawyer, Juniver Girsang, said the court should have referred to how the government addresses the issue of illegal plantations inside forest areas through the so-called omnibus law on job creation.

Passed in 2020, the law ushered in a wave of deregulation across a range of industries, including rolling back environmental protections and incentivizing extractive industries such as mining and plantations, with the aim to attract investment and create jobs. One of the omnibus law’s key concessions to the palm oil industry effectively legalizes the crime of illegal plantations in forest areas: It gives plantation operators a grace period of three years to obtain the proper permits, including the redesignation of the forest status, and to pay the requisite fines, allowing them to resume their operations.

“In the law, it’s clearly stated that encroachment into forest areas should not be liable to criminal sanctions, but administrative sanctions and fines instead,” Juniver said as quoted by CNBC Indonesia.

Surya also criticized the trial process, saying the failure to apply the omnibus law in his case denied him justice.

“My case has become a pilot project [since] the omnibus law isn’t being enforced [to legalize my plantations],” he said in a statement before the judges read their verdict. “Why am I the only one who’s being [criminally] processed whereas others with similar cases aren’t?”

Fugitive from justice

ICEL’s Raynaldo said the prosecution of Surya was based not just on the illegal nature of his plantations, but also the fact that he engaged in corruption and money laundering to obtain the illegal licenses.

In 2014, anti-corruption investigators charged Surya with allegedly bribing Annas Maamun, the governor of Riau province, where Indragiri Hulu district, in connection with his oil palm plantations. The 3 billion rupiah ($200,000) payment was allegedly meant to get Annas to amend a forestry bylaw for the benefit of Surya’s company, Duta Palma.

Annas was sentenced to seven years in prison for taking the bribe, but was released in 2019 after being pardoned by President Joko Widodo. For his part, Surya went on the run from law enforcement in 2014, remaining at large for the next eight years.

Authorities tried to prevent him leaving the country, but he somehow made it to Taiwan. Subsequent efforts to repatriate him were constantly thwarted, with Surya claiming medical problems.

It wasn’t until the Attorney General’s Office in August 2022 filed fresh charges against Surya, in connection with the bribery of Thamsir Rahman, that the fugitive decided to return to Indonesia. He was arrested upon his arrival in Jakarta on Aug. 15 by officers from the AGO.

Raynaldo said the corruption court’s verdict should inspire prosecutors in similar cases to look beyond any administrative violations a plantation company may have committed, and explore criminal conduct “which include corruption, human rights violation, forest fires and money laundering.”

The ruling should also prompt the Ministry of Environment and Forestry to reject pending requests from Surya’s companies to get their operations inside forest areas legalized, Raynaldo said.

“What’s important is to monitor these companies so that they don’t get amnesty because the court’s ruling clearly said that this is a huge issue and an extraordinary crime,” he said.

F.X. Herwirawan, the ministry’s head of forest area allocation, told Mongabay that the requests from Surya’s companies will be put on hold until after he’s exhausted his appeals in the criminal case.

Dirty palm oil finds its way abroad

During the trial, it emerged that palm oil from Surya’s illegally operating companies had ended up in the global supply chain. Agus Sudarmadi, the director of customs and excise at the Ministry of Finance, testified in December that export records from 2010 to 2021 showed the palm oil was exported to six countries: India, Malaysia, the Netherlands, Kenya, Italy and Singapore.

He added his office didn’t have a mandate to trace the source of the palm oil all the way back to the plantations.

This revelation makes Surya’s case a transnational one, said Made Ali, executive director of Riau-based environmental NGO Jikalahari.

He pointed out that the Netherlands and Italy, as part of the European Union, had agreed to stop the trade in commodities like palm oil that come from deforestation and illegal sources, under a no-deforestation bill that’s slated to be passed this year.

“When the European Union protests [against dirty commodities] through its new law that bans all exports from Indonesia to Europe [that aren’t sustainable or legal], it’s proven that our palm oil [still] comes from deforestation,” Made Ali said. “Maybe we can push Europe” to set a higher standard for traceability.

By Hans Nicholas Jong for Mongabay. Read the original article here