For better or worse, Indonesia is easing its already loose restrictions, with businesses and offices gradually reopening this month. It’s almost as if COVID-19 doesn’t scare us anymore despite the recent record spike in cases.

The caseload in Indonesia surged past the 40,000-mark last week, with a daily spike of at least 1,000 cases now the norm rather than the exception. Jakarta and East Java continue to be the worst-hit provinces thus far.

“This (spike in the number of daily reported cases) is also a result of the accumulation of previously unreported cases. [The data on new cases] must be averaged out weekly; this is more informative than viewing it on a daily basis,” COVID-19 Task Force spokesperson Achmad Yurianto said last week, adding that the government’s aggressive contact tracing partly explains the surge in cases.

But let’s take a closer look. Perhaps the spike wasn’t just correlated with contact tracing. Perhaps it was a deadly combination of the government’s lackluster COVID-19 response and the public’s indiscipline.

A rideshare driver named Mukhri Jatmiko told me this week that he’s not as concerned about COVID-19 as he used to be, and he’s certainly not gonna let it get in the way of his making a living.

“I stayed at home for two months,” he said. “I didn’t even activate my rideshare app. But I just don’t care right now. With the government now allowing us to work [outside], what’s the point in staying at home then? You can see how Jakarta’s traffic has returned to normal.”

Mukhri’s work-first-worry-later attitude is decidedly Jakartan amid this pandemic. He’s not the only one — KRL Commuterline recently reported an almost 50 percent passenger increase despite restrictions on its trains.

Whether people like it or not, the wheels in Jakarta — and all around the country — must keep turning. But herein lies the crux of the problem, and why contact tracing — despite recent innovations — may not suffice in halting transmissions of the coronavirus.

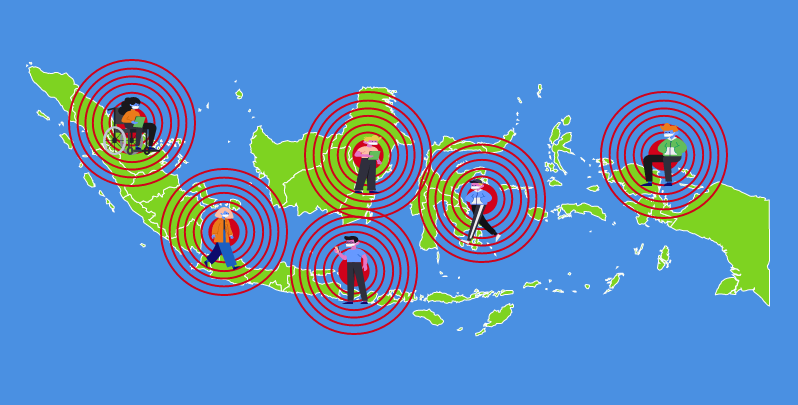

The current state of COVID-19 mass surveillance in Indonesia

On June 4, President Joko Widodo stressed that the country must make inroads toward aggressive contact tracing. The statement signaled a step in the right direction in this regard, but, at the same time, it was an indictment that Indonesia has yet to fully embrace the technology to track the spread of COVID-19.

As of today, there’s no quantifiable gauge as to the success of contact tracing nationwide, which perhaps speaks to the difficulty of surveilling some 267 million people. In smaller provinces, however, contact tracing is much easier to implement. For example, Gorontalo has made a contact tracing app mandatory for people traveling into the province, helping to identify its 230 confirmed cases as of June 22.

“It makes the job of the COVID-19 Task Force a lot easier. We can easily monitor the mobility of residents and newcomers,” said task force spokesman Sumarwoto.

That’s not to say there isn’t effort being made on the national front. The central government, for one, is trying to replicate contact tracing efforts like in Singapore, Hong Kong, and China. Rationally speaking, though, tracing works best at the beginning of an outbreak, not when it’s already out of control.

The government, along with startups, seem to be taking a better-late-than-never approach in having developed four major apps for contact tracing named Peduli Lindungi, Lapor Covid-19, 10 Rumah Aman, and Sekitar Kita, weeks after confirming the first cases in the country. Peduli Lindungi, developed by the Information and Communications Ministry, is the most popular of such apps, with the ministry claiming that it has been downloaded one million times.

But with contract tracing apps comes privacy concerns, which have moved those in the private sector to come up with innovative solutions. More recently, a new platform called Mass Tracing, which requires only WhatsApp to work, was launched by a group of engineers and activists in Indonesia and Singapore.

Mass Tracing is basically a “mobility surveillance” platform, wherein citizens can voluntarily share their coordinates to its WhatsApp number when they’re out and about. Users can then download their travel record and submit it to Indonesia’s COVID-19 task force in order to help break the COVID-19 transmission chain, especially as restrictions are eased in many major cities.

Khairul Anshar, one of the developers of Mass Tracing, said that the platform does not store private data since it utilizes WhatsApp’s encrypted messaging feature.

“All of the data are stored through WhatsApp and we don’t share it with third-parties,” he said. “It’s voluntary and requires the user’s consent. So users have full control.”

Damar Juniarto of SAFEnet, an organization promoting freedom of expression on the internet, said the efficacy of these apps and platforms is hard to prove since they rely solely on the willingness of the public to participate. The matter of where user data is stored also remains unclear.

“I think it’s a good initiative [to develop apps for surveillance]. But it’s like two sides of a coin,” said Damar. “On one hand, online health surveillance is important to curb the spread of the virus. On the other hand, the data privacy is not transparent. Is the data set stored in a state-owned or a third-party server?”

Privacy takes backseat

And yet, despite the ethical conundrum and without widespread surveillance on the ground, these apps are essentially reduced to storage-hoarding icons on your phones.

Countries with aggressive contact tracing, such as South Korea, Taiwan, and China have used sensitive details including CCTV footage, credit-card transactions, and location data from mobile phone users to track transmissions. Others have utilized Bluetooth technology to establish physical contact or proximity between mobile phone users, such as the TraceTogether app by the Singaporean government.

Both methods have had varying degrees of success. Practicality issues aside, Indonesia wouldn’t resist either of these methods if the public’s ordinarily relaxed attitude about privacy is anything to go by.

“Indonesians have a long history of being under surveillance.”

While Indonesia has not gone too far (yet) in implementing a draconian surveillance system, the importance of data security is often downplayed here. For example, Indonesia has yet to ratify the Data Privacy Laws and the country has been grappling with serious data breaches and abuses in recent years. In 2019, the government admitted to sharing the citizens’ e-KTP (electronic ID card) data to 1,200 private companies. Last month, e-commerce giant Tokopedia confirmed that 15 million of its customers’ data were stolen and sold on the dark web.

For now, the most draconian surveillance system has been implemented in the East Java capital of Surabaya, where COVID-19 transmissions have been at alarming levels in recent weeks. Even then, the city administration has stopped short of publicizing patients’ names and addresses, breaking down and revealing caseloads only down to the affected streets and public areas.

But maybe there’s more room for COVID-19 mass surveillance in Indonesia.

“Indonesians have a long history of being under surveillance,” said Damar. “When you have guests staying at your home for at least 24 hours, you are obliged to notify your neighborhood chief, for example. So I don’t think they care much if their data is abused by other parties. We never read the ‘privacy policy’ either. So that’s a problem.”

Or, as those handling the outbreak in the country might see it, an opportunity.