“I was born on 17th December, 1943 during the Pacific War,” Soe Hok Gie (史福義) began in his journal entry on Mar. 4, 1957. A rant followed.

“Today is the day when vengeance starts to petrify,” he continued. That day, he wrote about his geography exam score being deducted from 8 to 5. Believing himself to be the smartest kid in class, a 14-year-old Gie – as he was affectionately called – was livid about his score.

“An accumulation of vengeance goes into the heart and hardens like a rock. I threw away the exam paper. It’s okay if I am punished, but I never fail my exams.”

To Gie, the deduction was a grave act of injustice, as his teacher offered no valid reason for doing so. In a way, the entry showed Gie had a spark of intellectual rebelism about him even in his formative years, and how his unwavering fighting spirit led him to become a student activist during the Soekarno regime in the 1960s.

Gie’s diary, Catatan Harian Seorang Demonstran (A Diary of a Demonstrator), was published as a book in 1983. It has since become a celebrated must-read in Indonesia for activists and the general public alike. Gie wrote his diary and opinion columns for a national newspaper and student publications in a small, mosquito-infested dimly-lit room, according to Arief Budiman, Gie’s brother and academic-cum-activist, in the book’s introduction.

During his junior high school years, the legendary activist widened his horizons through reading, never constraining himself to any particular discipline as he absorbed everything from philosophy to classic Western literature.

Gie went to a Catholic school, where strict rules and order were a way of life.

“Most teachers in Catholic schools are dictators,” he said in an entry dated Feb. 14, 1958.

It was clear that Gie didn’t shy away from criticizing his teachers. In one incident, he retraced a debate that went down with his literature teacher over André Gide’s short story, The Return of the Prodigal Son. The teacher had argued then that the work was written by Chairil Anwar, an Indonesian poet and member of the “1945 Generation” of writers, while Gie was adamant that it was originally written by Gide and translated by Chairil.

“A teacher is not a God and is always right. And a student is not a cow,” Gie wrote at one point, casting suspicion that his scores may have been deducted because of his defiant attitude. He said that those who feel themselves to be beyond criticism should find their place in the trash.

Against the current

Gie may have been viewed as a headstrong radical by the powers that be. But he was shaped by the grim reality of his surroundings, constantly bearing witness to suffering among the working class. The post-National revolution era where Soekarno, Indonesia’s founding father, and his cronies seized power was to blame, according to Gie.

He wrote of his distrust of the Soekarno regime on Dec. 10, 1959: “I met a person (not a homeless person) who ate mango peel. He was hungry. This is a growing symptom in the capital city. I gave him 2.50 rupiah. I only had 2.50 rupiah at the time. Two kilometers from that person, our ‘majesty’(President Soekarno) is probably having fun, having a feast with his beautiful wives.”

After graduating from senior high, Gie started his journey towards activism at the University of Indonesia (UI), where he enrolled in 1961. As a student, he considered it an obligation to address social injustices. “The happy select few,” he described students. He also began to regularly write opinion pieces for national newspapers at this time.

It’s better to be exiled rather than fall into hypocrisy

Soe Hok Gie, Jul. 30, 1968

Gie had a colourful life as a university student. He hiked mountains regularly and helped to found the first nature exploration club at UI. In addition, he and his friends hosted film screenings and discussions on national politics, philosophy, and more.

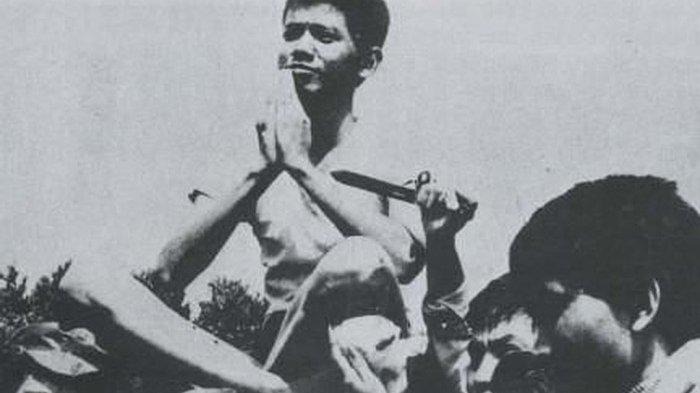

Gie joined a student movement against the Soekarno regime in 1966, raising three demands from the government: disbandment of the Communist Party of Indonesia (PKI), a reshuffle of Soekarno’s Dwikora executive cabinet, and lowering the price of essentials. The mass demonstration was spearheaded by the Indonesian Students Action Union (KAMI) and other groups, such as the Indonesian Labour Action Union (KABI) and the Indonesian Teacher Action Union (KAGI).

The mass demonstrations began on Jan. 10, 1966, often descending into chaos until Mar. 11, 1966, when Soekarno authorized military general Soeharto to conduct “Supersemar,” the Indonesian abbreviation for Order of Eleventh March. Supersemar gave Soeharto the authority to restore order by whatever means necessary, triggering the eventual transfer of executive power from Soekarno to the general. Soeharto went on to rule for 33 years in what is called the New Order era.

Although Gie was not officially a member of KAMI and did not hold any executive power in the students guild, he was influential in planning a protest on Jan. 11, 1966. He believed that all students should reject political pragmatism.

Life under Soeharto was not better than under Soekarno, by any means. Military influence was immense and corruption was widespread. Many of the era’s activists became complacent, turning a blind eye to the injustices to cozy up to Soeharto’s government and help build a fascist empire. Gie, however, was steadfast in holding onto his principles and never held any political position nor worked for the government during his lifetime, taking a teaching position at his alma mater until the end of his life.

“It’s better to be exiled rather than fall into hypocrisy,” Gie wrote on Jul. 30, 1968. He was depressed by the political climate and thought there were only two options for most people: apathy or flow with the current. But he chose to be a “liberated person,” exercising his right to criticize former friends and corrupt politicians, naming and shaming them in his published writing.

Like his fierce criticism against Soekarno’s government, Gie defied what Soeharto and his cronies stood for. He may have been anti-Soekarno and anti-communism, but still advocated for the release of the founding father’s supporters and left-leaning political prisoners.

It was during this time that Indonesia went through one of its darkest periods in history: the commmunist purge of 1965-66, during which an estimated 1 million people perished. Troubled by the genocide, Gie actively sought to tell the world about its horrors. He flew to Bali to witness the killings himself and wrote an investigative report for Mahasiswa Indonesia newspaper in December 1967 under the pseudonym Dewa. He became one of the first to publish horrific details about thousands of political prisoners being held in prisons and internment camps, and the despair of their families.

For many, it’s difficult to determine Gie’s political beliefs, as he had never committed to any mainstream political groups. But it was apparent that he was, first and foremost, a humanist, as well as anti-authoritarian and anti-establishment. In Gie’s obituary written by political scientist and friend Benedict Anderson in a journal, Gie used to refer to himself as an “anarchist,” often saying it with a smile.

“I write in part simply to relieve my sense of nausea at our condition. Sometimes, though, I feel as if it’s all useless. I feel that all there is in my articles is a few firecrackers. And I’d like to fill them with bombs,” Gie wrote to Anderson in a letter.

Gie’s legacy

In Indonesia, it wasn’t (and isn’t) easy to be an activist, much less to be an activist and Chinese-Indonesian. Every Chinese-Indonesian may have been told, at least once in their lives, to stay under the political radar in order to survive.

As we have come to learn throughout the years, Gie’s activism made him a target of racial hatred. In one instance, he received hate mail that said, “What an ungrateful Cina, go back to your country!” using a derogatory slur towards the ethnic Chinese minority group.

Arief Budiman said their mother had often worried about the youngest son. “Gie, what is the worth of your actions? You only find enemies [and] don’t receive any money,” Arief recalled his mother telling Gie. At the time, Gie simply responded: “You don’t understand, mom.”

Yet toward the end of his life, Gie began to contemplate what his mother had tried to say. Before he died in December 1969, Gie shared his worries and desperation with Arief: “I keep thinking these days, what is the worth of the things I did? I write and criticize many people that I consider corrupt. After all of that, I got more enemies and more people who misunderstood me. And my critics don’t change anything. I want to help the oppressed working class, but the situation isn’t changing, and what is the worth of my criticism? Doesn’t it feel like a joke? Sometimes I feel extremely lonely.”

A strong loving feeling dominated me. I want to give this love to every human, dog, and everything

Soe Hok Gie, Dec. 2, 1969

I’ve felt that same loneliness. Chinese-Indonesians are often considered outsiders, and it’s challenging when we try to make ourselves heard. When we raise questions and fight against social or political injustice, we become subjects of ridicule, often on the receiving end of unduly hatred. Then, nothing changes.

As a Chinese-Indonesian, I know I have the option to stay silent. I can be a model minority and keep quiet about the injustices happening around me, while preparing myself to one day become a victim. But it was Soe Hok Gie who opened my eyes.

I learned his name when I was 16, and then I read his book. He has helped me navigate through my identity as a Chinese-Indonesian, and showed me the injustices that persist in Indonesia.

Every day, I read his journal entries, which are relatable to my own experiences. It often feels like Gie knows about my feelings and problems, as a Chinese-Indonesian who often has to face racism and bullying – as if I’m having an honest conversation with a good friend.

I’m 21 now, and I still regularly read his diary. For me, it’s not just a diary, but a reminder to hope for a better future – that it’s okay to dream. He’s shown me how to fight and say: “Enough is enough. I don’t want to be a victim in this unfair system anymore.”

Soe Hok Gie’s life is perhaps a poignant example of human tragedy, one that may be described as poetic too. He now rests in peace in his favorite place: the mountain.

It seems that he had foreseen his passing prior to hiking Mount Semeru, where he inhaled toxic gas and died.

On Dec. 2, 1969, Gie wrote, “I don’t know why I feel melancholic tonight. Maybe it was the long nap. I saw streetlamps on the streets in Jakarta with a new color. Seems like it was diluted into a face of humanism. Everything felt romantic but empty. I felt like I was liberated… A strong loving feeling dominated me. I want to give this love to every human, dog, and everything.”

“Tonight is so strange. This feeling is not a common feeling for me.”

On Mount Semeru sits a placard dedicated to Gie and Idhan Lubis, a friend who had also passed away during the hike.

Gie died one day before his birthday on Dec. 16, 1969. He was 26.

Gie had once considered what it means to die at a young age, writing down the following entry on Jan. 22, 1965.

“A Greek philosopher once said that the most well-fated destiny is not to be born, the second is to die young, and the worst is to age. I kind of agree with this. Be happy for those who die young.

Small creatures come back.

From nothingness to nothingness.

Be happy in your nothingness.”

I believe Soe Hok Gie has found his joy, while his spirit lingers to this day, standing up for the oppressed through all of us who dare to stand up against injustice.

Also Read — Searching for The Sin Nio, the forgotten Chinese-Indonesian hero