Indonesia’s Information and Electronic Transactions Act (UU ITE), which criminalizes any electronic media communication that could be considered defamatory or slanderous, is often criticized as being shockingly harsh, and, in particular, oppressive to freedom of speech.

UU ITE’s vague definition for defamation and slander is often used as a tool to criminalize internet users for posting content that wouldn’t be problematic in a society where freedom of speech is better protected. The most recent example is when a cultural group reported two Facebook users to the police for mocking a traditional Bataknese costume worn by President Joko Widodo. They felt insulted because they argued that mocking the costume was the same as mocking the entire Batak culture.

But that case pales in comparison to some UU ITE violations in the past. From libel to sharing “immoral” content and “pornography” online, these are some of the most outrageous ways Indonesians have been victimized by UU ITE:

“Coin for Prita”

In 2008, Prita Mulyasari was understandably upset when she was falsely diagnosed as having dengue fever at South Tangerang’s Omni International Hospital. She wrote an email complaint to the hospital, which she later forwarded to her friends on a mailing list. The email then spread online in internet chat groups, which led to the hospital suing Prita for libel.

On May 11, 2009, the Tangerang District Court ruled that Prita was guilty of libel and ordered her to pay the hospital Rp 204 million in damages. But thankfully, Prita wasn’t alone. When her story started making national headlines, her supporters and critics of UU ITE started a fundraising campaign called “Koin Untuk Prita” (Coin for Prita), which managed to pool together Rp 825 million for Prita to pay her fine.

At least this story had a happy ending for Prita. After several appeals in higher courts, the Supreme Court overturned her conviction in 2012. However, despite the national attention this case gathered and how it highlighted flaws in UU ITE, lawmakers at the time did not amend the law even when they said they would.

Freedom to choose one’s religion (but not atheism)

The good name of religion is also protected by UU ITE. In 2012, Alexander An AKA Aan, from West Sumatra, argued against God’s existence in an atheist Facebook group. Aan’s post found its way to the authorities and the civil servant was soon prosecuted for inciting religious hatred in violation of UU ITE and was sentenced to two and a half years in prison on June 2012.

Aan served 19 months of his prison sentence before he was released on parole. Reflecting on his case, Aan said in an interview with the New York Times that he did not intend to incite religious hatred in his posts on Facebook, rather that they were meant for discussions about religion.

But, unsurprisingly, Aan said he no longer engages in religious discourse online these days.

Husband has wife arrested for chatting with male friend on Facebook

Even spouses can turn on each other using UU ITE. In 2011, Bandung man Haska Etika unethically hacked into his then-wife Wisni Yetty’s phone to find the Facebook chat log between her and an old friend from middle school named Nugraha.

Haska later used this as ammunition against Wisni after she reported him in 2013 to the police for domestic violence after he had filed for divorce earlier that same year. Citing “immoral” messages in the chat log, Haska reported Wisni to the authorities in February 2014 for violating the prohibition of transmitting immoral content online as stipulated in UU ITE.

The Bandung District Court ruled against Wisni in March 2015, sentencing her to 5 months in prison and a fine of Rp 100 million. Thankfully, Wisni appealed her sentence to the Bandung High Court, which overturned her initial conviction in August 2015.

Wisni and Haska are now happily divorced.

Sued for slandering a whole city

Florence Sihombing, a student at Yogyakarta’s Universitas Gajah Mada (UGM), got in trouble for an incident at a petrol station in 2014. According to her, she wanted to get her motorcycle filled up with the more expensive Pertamax fuel so she should have been entitled to skip the motorcycle queue and go to the shorter car queue. After being told to queue with the rest of the motorcycles, she posted an angry status on social networking site Path deriding the city of Yogya as being “poor, dumb, and uncultured.”

Florence’s post quickly went viral and she became the target of much internet scorn, particularly from Yogya citizens. Even though Florence apologized for her post (even to Yogya’s Sultan Hamengkubuwono X), she was arrested in August 2014 by the Yogyakarta Police on defamation charges. She was then found guilty by the Yogyakarta District Court in March 2015 and was sentenced to 2 months in prison, a 6-month probation period, and a fine of Rp 10 million. Her subsequent appeal to the High Court was rejected.

Sate seller skewers himself with pornographic memes of the president

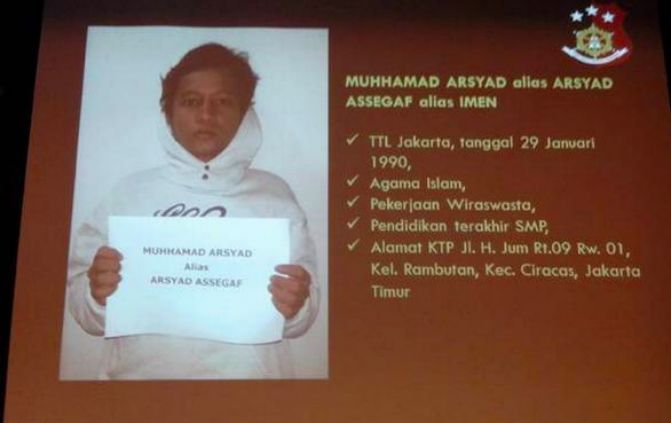

When President Joko Widodo was elected in 2014, many hoped he would be a champion for freedom of speech in Indonesia. Those hopes were soon dashed when, in late October 2014, just mere days into Jokowi’s presidency, a 24-year-old sate seller by the name of Muhammad Arsyad was arrested for insulting the president.

His crime? Muhammad photoshopped Jokowi’s and PDI-P Chairwoman Megawati Soekarnoputri’s faces onto nude porn actors who were pictured performing sexual acts and shared them online (to be fair, many people created memes like this poking fun at both Jokowi and losing presidential candidate Prabowo Subianto during the tense political atmosphere of the 2014 presidential election).

While Jokowi did not order Muhammad’s arrest, the sate seller was reported to the police by a politician from the PDI-P party, of which Jokowi is a member. Jokowi eventually pardoned Muhammad and ordered his release.

Hope for amendment?

There have been repeated calls over the years for UU ITE to be amended, but many observers believe that politicians and other elites love the law as it stands since it can be used to silence their critics.

However, Parliament did promise to make amendments to the law by mid-October. Unfortunately, Communications Minister Rudiantara recently hinted that the amendment would not change UU ITE’s fundamental flaws (such as its ambiguous definitions of defamation and slander). Instead the proposed amendment would reduce the maximum prison sentence for violating the law from 6 years to 4. Suspects would also not have to be in police custody while their cases were being investigated.

If it’s not properly amended, UU ITE can and will continue to be used as a tool to silence those with legitimate criticisms against the powers that be, which is exactly what freedom of speech is supposed to protect us from. As long as it exists as it is, UU ITE will hold Indonesia back.