Hundreds of thousands of women around the world marched on the weekend to demand their rights and remind those in power that women’s rights are human rights. These women are fighting for a wide range of issues: reproductive and sexual health, equal pay, political representation, and an end to violence and discrimination against women, among many other topics.

One key demand is that women should be able to live without threats to our safety and security. This means that women must be free from abuse and harassment in our homes, in our workplaces, and on the streets.

By May 2017, I will have lived in Indonesia for five years. The last four of these have been in Jakarta. I have volunteered and worked with a range of women’s organisations such as Koalisi Perempuan Indonesia and ‘Aisyiyah, and have spent the last two years working on an international development program that places women’s health at its heart. I care deeply about Indonesia’s women and girls, and will fight alongside them for the fulfillment of their rights for as long as they will graciously allow me to do so.

ALSO READ: Fighting Back: The women working to end street harassment in Jakarta

About two weeks ago, I decided to conduct a short experiment: what would happen if I walked, alone, from my home near Pasar Mayestik in South Jakarta to Plaza Senayan? As a twenty-something white woman, I expected I would receive a fair amount of sexual harassment, to which I am unfortunately no stranger. I am harassed on the streets of Jakarta nearly every day – previous incidences of harassment range from the very minor (“Hey mister, you like sex?”) through to more serious physical forms (having my breasts grabbed by a passing motorcyclist).

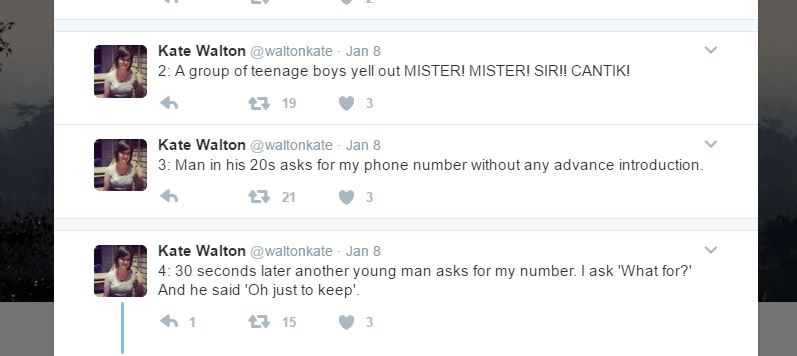

The walk took only 35 minutes, and included both quiet streets and major ones such as Jl Pakubuwono. On the spur of the moment, I decided to also live tweet what I experienced:

By the time I reached Plaza Senayan, I had been harassed 13 times by 15 men and boys:

I had expected these sorts of comments, looks, and requests for my phone number. After all, they were no more sinister than what I experience every other day on the streets of Indonesia’s capital.

What I had not expected was the amount of outrage that my live tweeting of the harassment would garner. Hundreds of Jakartans interacted with me on Twitter, expressing both shock and sadness at what Jakartan men flung at me:

Many women and girls also shared with me some of their experiences:

“My mother was once grabbed from behind by a man she didn’t know. That made me truly aware about this issue.”

It should be noted that I was never in serious danger, and that most of these comments, in the great scheme of things, were fairly harmless and banal.

What makes being a target of sexual harassment exhausting, however, is the sheer frequency with which it happens: every single day. It saddens me that I have to admit that I am not safe from sexual harassment anywhere in this city: not in its malls or offices, nor in its restaurants or on its streets.

It is tiring to have to be prepared to face off against men every moment you step outside your front door. Your body becomes tense, and you find yourself staring at the ground as you walk, because you do not want to meet anyone’s gaze and find that they are gazing at your breasts or legs. You withdraw from social interactions, and pretend to play on your mobile phone while waiting for your soto ayam from the seller on the corner. It is so, so exhausting.

“What was experienced by @waltonkate also happens in bus terminals, bus stops, stations, inside trains. Yep, almost everyday. It’s traumatic because it’s so frequent. “

I already do my best to reduce levels of sexual harassment: I wear leggings underneath any skirt or dress that doesn’t reach my knees, and cardigans over tops without sleeves. It makes no difference, as many other women have pointed out:

Indonesia’s Commission on Violence Against Women, Komnas Perempuan, recorded 321,752 cases of violence against women, including sexual harassment, in 2015.

Let me be clear: sexual harassment is a form of violence against women and girls. It is threatening and reminds us of how we are seen by broader society: as objects for men’s enjoyment and use.

How can this still be the case in 2017?

Will the candidates for the DKI Jakarta gubernatorial election this year do anything about the fact that the city’s women and girls feel uncomfortable, unsafe, and threatened on its streets and its public transport? We will have to wait and see.