The Sin Nio (pronounced Teh Sin Nyo) was a Chinese-Indonesian woman who fought the Dutch during the National Revolution in the 1940s. She was the only woman in her company, doing her part in the struggle as a foot soldier and a paramedic.

There are unavoidable parallels to Chinese folk hero Hua Mulan, as The Sin Nio fought not as herself, but disguised as a Javanese man with the pseudonym Mochamad Moeksin. A woman joining the revolution was unthinkable then, let alone a Chinese-Indonesian woman.

Yet while Mulan has gained global recognition thanks to two Disney blockbusters, The Sin Nio is barely recognized as a national hero in Indonesia.

It’s difficult to find anything about The Sin Nio in the history books. Even online, in my research for this story, I was only able to find two or three articles about her, and they were mostly concerned with the Mulan comparisons.

There was practically no account of what drove her, what her idea of freedom was, and how she lived her Chinese-Indonesian experience. My attempts to contact one known living relative bore no fruit, so I had little foundation on which to give an accurate account of who The Sin Nio really was.

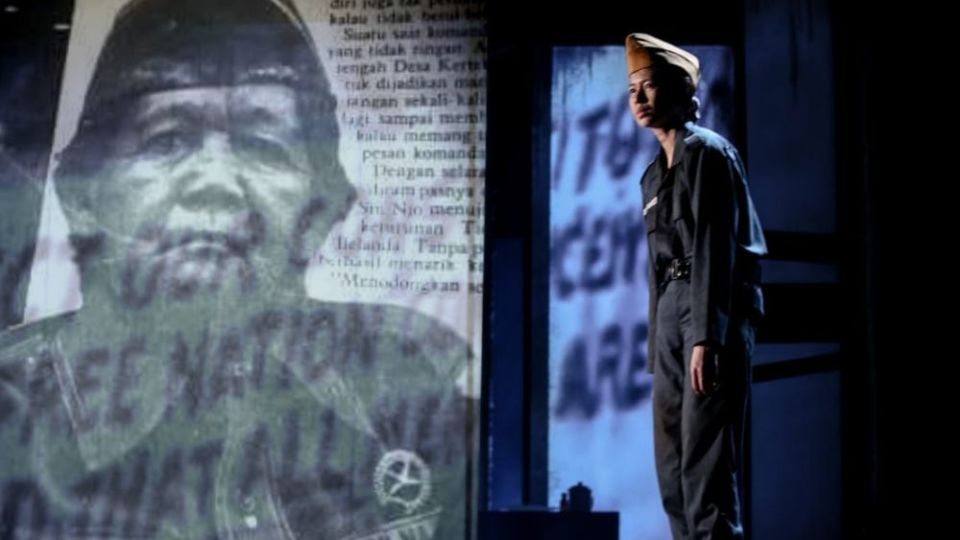

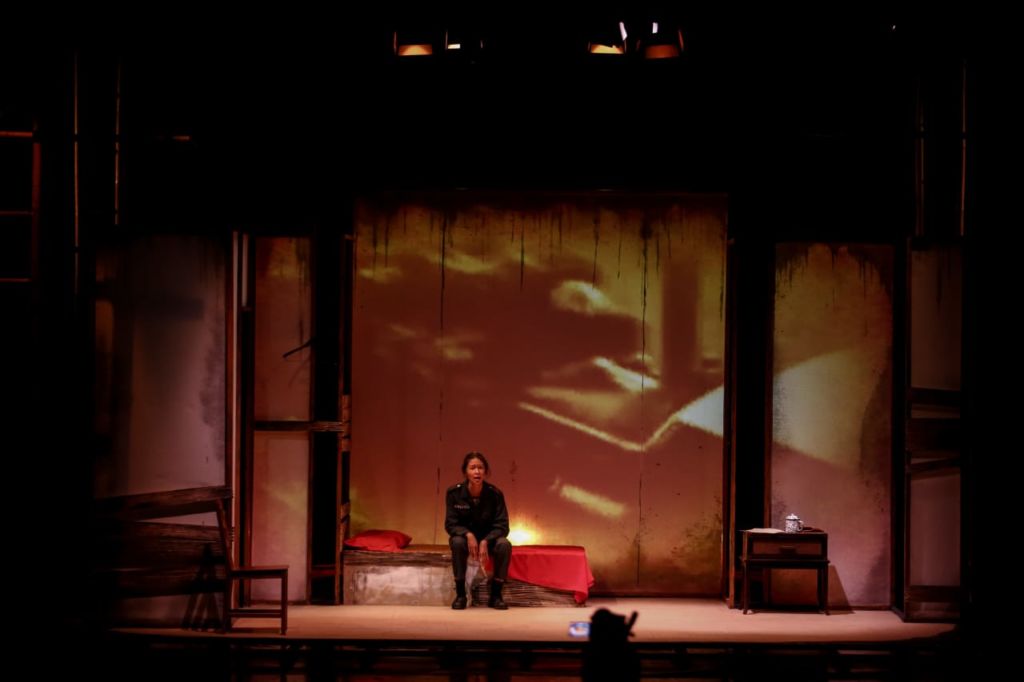

Then came Sepinya Sepi (A Quiet Desolation), a theatrical drama based on The Sin Nio’s life starring renowned actress Laura Basuki in the lead role. It was a stage act performed for two days, commissioned by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology as part of their Di Tepi Sejarah (On the Edge of History) series to showcase lesser known national figures.

The story starts with The Sin Nio as a pensioner, living on her own in a small shack near Central Jakarta’s Juanda train station. As she recalls her life, we learn that she was born in Wonosobo, Central Java, to a family that makes and sells kue mangkok (steamed cupcakes).

In a monologue, The Sin Nio talked about her ideals, which are founded on principles of humility.

As such, The Sin Nio did not hail herself as a hero, but as someone who needed to do what became necessary as a human being experiencing the collective struggle of living under the clutches of colonialism. By volunteering to be part of the revolution, she not only showed her nationalism, but also made a loud statement of what it meant to be Chinese-Indonesian.

To her, unity between races was essential in overcoming the colonials’ divide et impera strategy of butting Indonesians of various race and creed against one another.

Chinese-Indonesians were often employed as intermediaries for unpopular work by the Dutch, most notably in tax collection, while pribumi (a term that roughly translates to native Indonesians) citizens occupied a place at the bottom rung of society. This created tension between the two races, even though both were oppressed by colonialists. Nonetheless, fairly or otherwise, Chinese-Indonesians developed a reputation of being opportunistic, cunning, and deceitful.

The Sin Nio saw through the hate, even though her sibling was killed in a violent reprisal fueled by anti-Chinese sentiment. The tragedy spurred her fighting spirit and her drive to show solidarity with fellow oppressed Indonesians — regardless of race.

Her sacrifice unpaid

Safe for the Mulan comparison, there were no specific accounts of The Sin Nio taking part in Hollywood-esque battles. She was just as remarkable and heroic as everyone she fought alongside with, and that obscurity from the public eye suited her.

After the war, The Sin Nio sought to live a comfortable life into her old age. But her life was tumultuous; she had six children from two failed marriages, yet mostly lived alone as a widow. Amid the loneliness, she often wondered what she had done to deserve such a tragic fate.

The Sin Nio flew to Jakarta in 1973 to validate her status as a war veteran, which would grant her access to pensioner allowance. She did not have a permanent address in the capital, moving around and finding shelter at the office of the Veterans Legion of the Republic of Indonesia, as well as a mosque. She often wore her war uniform to remind people of her past, even though complicated bureaucracy prevented her from getting that recognition.

On Aug. 15, 1981, The Sin Nio’s application was finally granted, but it did not initially come with the financial support she desperately needed. After several more years of struggling to gain her rights, she was finally granted a monthly allowance of IDR26,000 (US$1.83) per month, which barely covered her living costs. She had no choice but to live a modest life in her final days, making a home out of a small shack near Juanda train station until she passed away in 1985.

Despite all the hardship, The Sin Nio never regretted her decision to become a guerrilla fighter. However, as somebody with the same racial background as her, I can certainly sympathize with her disappointment and disillusionment. I, too, have often found myself asking the same question she posed in the play: “Was I treated this way because I’m Chinese-Indonesian?”

Being Chinese-Indonesian can be traumatizing, especially for women. Even after the revolution, Chinese-Indonesians still face systematic racism and violence, most notably the communist purge in 1965, in which at least 500,000 Indonesians were massacred, and the targeted racial-based violence against Chinese-Indonesians in 1998.

Monika Winarnita, a lecturer at Australia’s Deakin University, said, “Women’s testimonies have also been framed as either violence against all women or violence against the group as a whole, while their specific experience of gendered racial violence is often overlooked,” referring to the rape and murder of hundreds of Chinese-Indonesian women amid the May 1998 mass riots in the country.

As if we have to justify our nationality, Chinese-Indonesians are often asked to give back to the country. Being seen as neither of one race nor the other can be an existential dread. It becomes more than just a question of nationality — it’s also about identity. Who are we, really?

The answer is, perhaps, that we are different to other Indonesians in the way that every individual is different, but the same in the way that we all have our commonalities.

In the play, The Sin Nio’s Javanese accent was very thick, and she spoke in Chinese on just one occasion. Heliana Sinaga, the stage director of Sepinya Sepi, said much of the play was grounded on thorough research of The Sin Nio’s life, though noting that some aspects were products of artistic liberties, including her speaking Chinese, to emphasize the duality of her racial identity.

Preserving The Sin Nio’s legacy

Some heroes are hailed, some are remembered. Some have statues made of them. But 70-year-old The Sin Nio died alone in Jakarta. Her final resting place in Layur public cemetery, Rawamangun is nondescript and indistinguishable from dozens of other graves, almost forgotten.

Charlotte Setijadi, Assistant Professor of Humanities and Coordinator at Singapore Management University, said the making of national heroes is largely driven by state-led narrative. Chinese-Indonesians are often left out from the conversation, particularly during President Soeharto’s New Order period.

“Chinese Indonesians were so foreign and so ideologically and politically regarded to be ‘unclean’ that they had to be assimilated almost immediately after the New Order regime came into power. To include these people who needed to be assimilated as part of the national revolutionary narrative doesn’t quite fit. This is why Chinese-Indonesians are largely excluded from the narrative about independence,” Charlotte explained.

Yet it’s a testament to her sacrifices that we remember the name The Sin Nio all these decades later. Beyond the Mulan similarities, she proved that anybody — even someone who was ostensibly among those at the bottom rung of the social hierarchy — could carve her legacy into this nation’s rich history. In a way, she was a true feminist who was way ahead of her time.

It falls to us to relive her ideals, to remember her story, and to learn from her legacy. Like The Sin Nio, there were many Chinese-Indonesians who gave their all to liberate people from the chains of oppression but faded to obscurity. They should be remembered not because of who our school history books tell us to celebrate, but for what they believed in and fought for.

As The Sin Nio said in Sepinya Sepi, “There’s nothing that I regret. I chose to join the revolution, although I know history won’t remember me. This is the reason I’m not afraid of being forgotten. The important thing is that I did my duty for what I believed in.”