While there is a movement among Indonesian women to fight back against the country’s epidemic of street harassment, most victims still do not report incidents of harassment to the police, often due to embarrassment or a lack of evidence such as eyewitnesses or CCTV. Those that do get reported are unlikely to be prosecuted, especially when there is no proof of the harassment.

“The police say my case is progressing quickly,” said 22-year-old Amanda said, who was groped in Depok on January 11. “But I think it is only because I made it go viral. Sexual harassment happens all the time, but people – including the police – don’t see it as a real problem.”

Amanda was walking to the Pondok Cina train station in Depok on Thursday, January 11, when a man drove up beside her and violently groped her breast.

“Suddenly there was this guy close behind me, so I thought he wanted to ask an address,” Amanda said, smiling wryly. “But he actually stopped next to me, grabbed me, and with his right hand accelerated his motorbike to get onto the main road. I screamed at him, but it was quiet there so no-one heard.”

Amanda quickly noted the man’s license plate number on her mobile phone and texted her friends. They offered to help her to report the incident to the police. She saw that there was a house with CCTV cameras and knocked on the door to ask for the recording.

“I was shaking and crying,” she said. “I told the man what had happened, and he said he would WhatsApp me the recording.”

This meant that when Amanda got to Polres Depok to report the harassment, she was able to show the police officers the video. But rather than assisting her, Amanda says they made her wait for hours and forced her to go back and forth between different units.

“First, they sent me to the Integrated Police Services Centre,” Amanda recalled. “They gave me a form but when I told the officer what had happened, he said I had to go to the General Crime Unit.”

So she went there, repeated her story, and was again told she was in the wrong division. “They said it was a problem for the Women’s and Children’s Protection Unit, so my two friends and I went there, but no-one was there.” They ended up waiting one hour before the responsible officer showed up and they were able to fill out the form. Amanda was not given any receipt for the report.

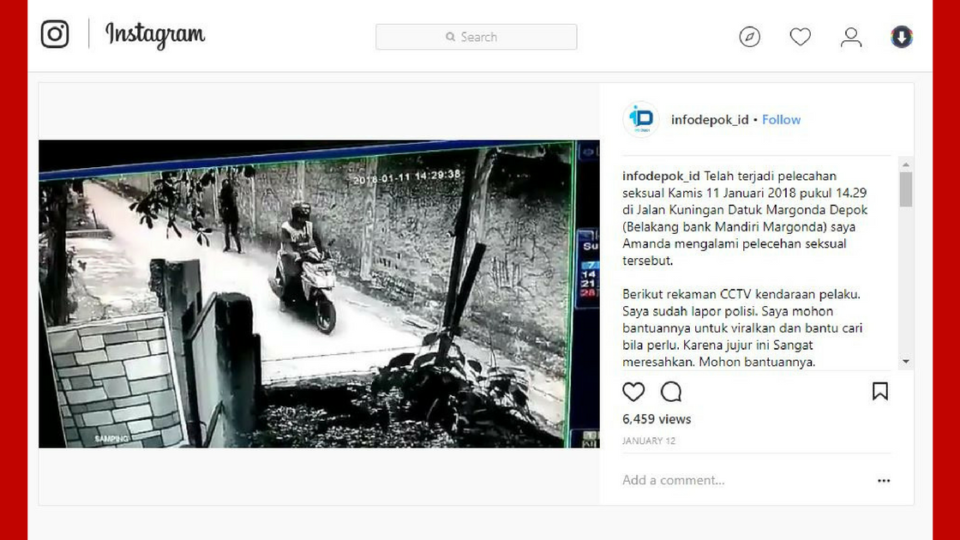

“I felt disappointed with the services,” Amanda said. “I thought my report would probably not get processed. So I went to an Instagram account with lots of followers, @InfoDepok, and asked them to help make my case viral.”

https://www.instagram.com/p/Bd09knQjygr/?utm_source=ig_embed&utm_campaign=embed_ufi

The next morning, police from Polsek Depok came looking for Amanda. “They were surprised,” she said, laughing. “I told them I’d reported it to Polres Depok but they hadn’t heard about it from them – they had seen the video online! I told them that I did that because I felt my report was going to be ignored, that they hadn’t had any empathy for me at all. They were clearly annoyed that I’d made it go viral.”

More police arrived, this time from Polres Depok, where Amanda had first reported the incident, and took her to the station to make a complete report. “I told them I’d already been there, but they didn’t say anything. They finished their report and I went home.”

Two days later, Amanda heard from a journalist that the 29-year-old perpetrator had been caught. On Tuesday morning, she and her friends went to the police station to meet him. “I asked him why he did it, but he just kept going around in circles,” she said. “He said he had khilaf [made a mistake], because he was stressed – his wife and father had died, he didn’t have a job, so on. I told him there was nothing that could justify what he did.”

When Amanda left the room, her male friend, Arief, went in. Perhaps feeling that another man would understand him, the perpetrator was more relaxed, and told Arief that he had done it iseng, a slang word meaning ‘for fun’, or ‘for no real reason’. Arief was furious and left immediately.

Amanda and her friends were astonished when the man’s father and younger brother turned up to apologise for him. “His father told me his son was a good person,” Amanda recounted, raising her eyebrows. “He even said he was a religious expert himself, owned a pesantren [Islamic boarding school], and was a friend of [former president] Gus Dur… I told him that his son was 29 years old and needed to be responsible for his own behaviour.”

Despite many people believing a woman’s clothing alters her likelihood of being harassed, Amanda reminds us this is not true. “I was wearing a hijab at the time,” she said, pointing at her headscarf. “With a loose shirt and long pants… Many women who wear chador even become victims of sexual harassment. The perpetrators don’t look at what sort of clothes women are wearing – they do it anywhere it’s quiet.”

After meeting Amanda, the man was released from police detention and allowed to go home. “The police said it is because the Criminal Code article he will be charged under, Article 281, the maximum sentence is five years,” Amanda said (for crimes with a maximum sentence of five years or less, suspects generally cannot be detained before trial). “I was disappointed, but there’s nothing I can do about it.”

“Now I just have to wait for my case to be taken to the District Attorney,” she added. “The police called me in again on Friday. They told me the man who groped me is depressed, that he keeps yelling about wanting to kill himself… I could only shrug and go home, wait for updates.”

Amanda has simple hopes for her case: she wants to show people that sexual harassers can be punished in Indonesia. “I don’t want revenge or anything like that,” she said, shaking her head. “I want this to be a deterrent for other potential harassers… I want them to see that they can’t just go around grabbing anyone they want.”

Activists would argue that the bureaucratic difficulty faced by Amanda in reporting her harassment, even with strong evidence, is proof that Indonesia desperately needs new, stronger laws to protect women from gender-based violence such as sexual harassment. A bill that would do just that (the Law on the Eradication of Sexual Violence) was drafted but has been in discussion in parliament since 2014.

Even as the draft for the Law on the Eradication of Sexual Violence languishes, political parties are currently rushing to show their support for a draft revision of the country’ criminal code that would make consensual sexual acts between adults of the same gender illegal. The moral panic over LGBT rights has also hit Amanda’s city of Depok, where the mayor has recently talked about bringing the community together to work together to solve the LGBT problem.

Amanda had something she wanted to say about that too.

“I would also like this say to the Mayor of Depok… Don’t focus on LGBT only. Depok is facing serious challenges of morality. Please try to be more concerned about women’s and children’s protection.”