L, who asked that we not use her full name for her safety, is a Surabaya resident who goes to college in Malang. For practical reasons, she braved the three-hour ride to bring her motorcycle to her new home.

After three years of living in Malang, L knows full well not to take out her vehicle — which sports Surabaya license plates — anytime her hometown soccer team Persebaya takes on Malang’s Arema. She knows that doing so could make her a target for soccer hooligans, especially after an Arema defeat.

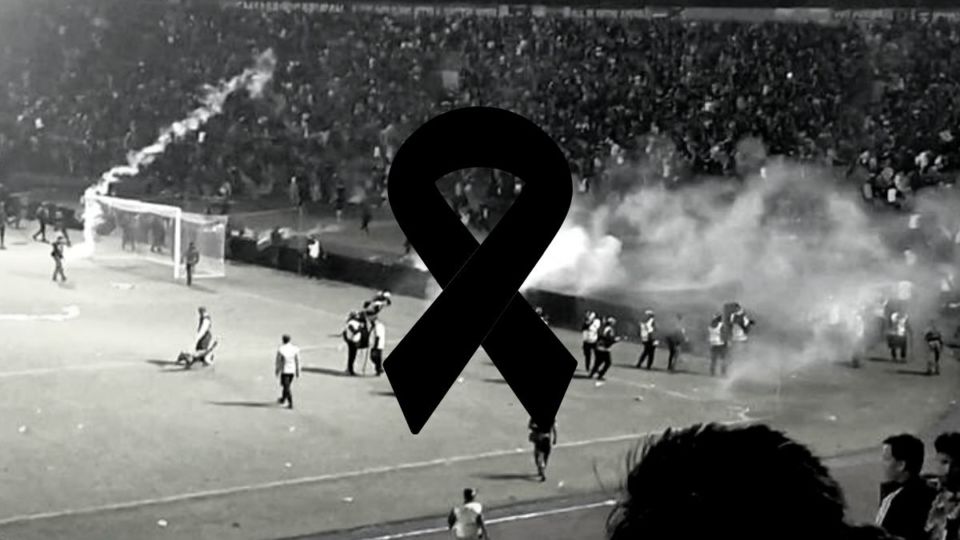

Headlines about spectator violence have marred the reputation of the beautiful game in soccer-obsessed Indonesia. They are also why many of us — ourselves included — initially cast most of the blame for the Kanjuruhan tragedy on hooligans.

For a long time, it had been easy to blame Indonesian soccer’s shortcomings — particularly on the fandom front — on hooliganism.

Not after Oct. 1, it seems.

More footage has emerged from the stadium in the days since the tragedy, showing instances of excessive brutality from police officers and military personnel to quell what looked like a manageable case of pitch invasion. Despite the pleas of spectators who did not participate in the riots, we can see videos of police officers firing tear gas into the stands, where children were present.

By the latest count, of the 131 people who died in the tragedy, 33 children were children — the youngest being a 4-year-old.

The blame game has quickly shifted from hooligans to law enforcers and soccer officials. Simply put, it’s hard to imagine that the Kanjuruhan death toll would be so high if police had refrained from firing tear gas, which triggered the deadly stampede, and if spectators had not been forced to squeeze out of the only two narrow exits that were open at the time.

That’s why heads are beginning to roll among the police force, with 10 commanders, including Malang’s police chief, having already been removed from their posts. Meanwhile, the National Police’s Internal Affairs Division continues to probe dozens of officers over the firing of tear gas in the stadium.

It seems failures related to security management, and not hooliganism, is the main factor holding back a restart of top-level domestic soccer in Indonesia.

A matter of admin and death

The game’s international governing body, FIFA, banned Indonesia from world soccer for a year in 2015 over the relatively trivial administrative matter of the government’s interference with the PSSI (Indonesian Football Association).

FIFA has yet to impose any sanctions on Indonesia in the wake of Kanjuruhan despite the scores of lives lost.

The government would be right to worry about any more bans, given that Indonesia is hosting the FIFA U-20 World Cup in May 2023. Sports Minister Zainudin Amali’s woefully ill-timed statement expressing his concern that the tragedy could jeopardize Indonesia’s hosting of the tournament speaks volumes of the government’s priorities.

Yet once the government sets its sights on a task, it has shown itself to be capable of commendable work.

Take the 2018 Asian Games. With the eyes of the continent firmly on Indonesia, the government pulled out all the stops to deliver an all but flawless major sporting event. Where there’s a will, there’s certainly a way.

It’s hard to imagine the U-20 World Cup would be any different. We will likely once again see venues revamped for the tournament, with ample security measures in place to ensure fun for the whole family at matches.

One can safely bet that, after the recent tragedy, security forces won’t employ a heavy-handed approach on spectators, many of whom will be of a completely different profile to the predominantly working-class who attend domestic league soccer matches. There certainly won’t be any tear gas used at the stadiums, at least, since it is banned by FIFA under its matchday safety and security regulations.

Unless FIFA says otherwise, the U-20 World Cup may kick off as scheduled and it may even end up being a fantastic showcase for the rising stars of world soccer.

Meanwhile, the domestic soccer league has been suspended indefinitely, at the explicit order of President Joko Widodo, while the official investigation into Kanjuruhan continues. When the league resumes — and it will, in all likelihood, due to its immense popularity — security personnel must value the lives of its spectators as highly as they did for those who attended the 2018 Asian Games and those who will attend the upcoming U-20 World Cup.

Respect is a key component of the beautiful game, and it must be given to and earned by everyone involved. Only then can Indonesian soccer rise from obscurity to a level that matches the people’s obsession with the sport.

After Kanjuruhan, Indonesian soccer is well into injury time, but the final whistle has not yet blown on it being able to make a dignified comeback.

More from Kanjuruhan

‘Humanity above football’: Thousands of Persebaya fans mourn Kanjuruhan tragedy victims

Kanjuruhan tragedy: National Police launch internal probe over tear gas

National Police chief offers Kanjuruhan victim’s brother a spot in the force

Police justify ‘last resort’ tear gas use in deadly Kanjuruhan soccer riot