Aulia hasn’t had the time to take a breather during what she has described as an exhausting months-long marathon. Ever since Indonesia officially recorded its first COVID-19 cases half a year ago today, Aulia and her case tracer colleagues have practically lived out of the Puskesmas (community clinic) in Menteng, Central Jakarta where they work.

“No rest. My phone keeps ringing. I even work on weekends,” Aulia told Coconuts.

Being an epidemiologist tasked with identifying and recording COVID-19 cases in the commercial heart of Jakarta is overwhelming, to say the least.

Aulia started tracing COVID-19 cases when Indonesia officially recorded its first case of the disease on March 2, which happened to be of a Depok, West Java citizen who had visited a bistro in Menteng shortly before she tested positive.

Aulia has since gone out almost everyday for close contact tracing of Menteng residents who were infected with the coronavirus.

The most crucial pieces of information that can be obtained from patients are the number of people they have recently come in close physical contact with, and, if fortune favors the tracers, where these people can be found.

Once close contacts are identified and located, Aulia would insist that they isolate at home as they wait for test results.

There’s also the matter of tracking down close contacts of the close contacts, which gets more difficult with each additional infection link. Sometimes, it feels like losing a race against time.

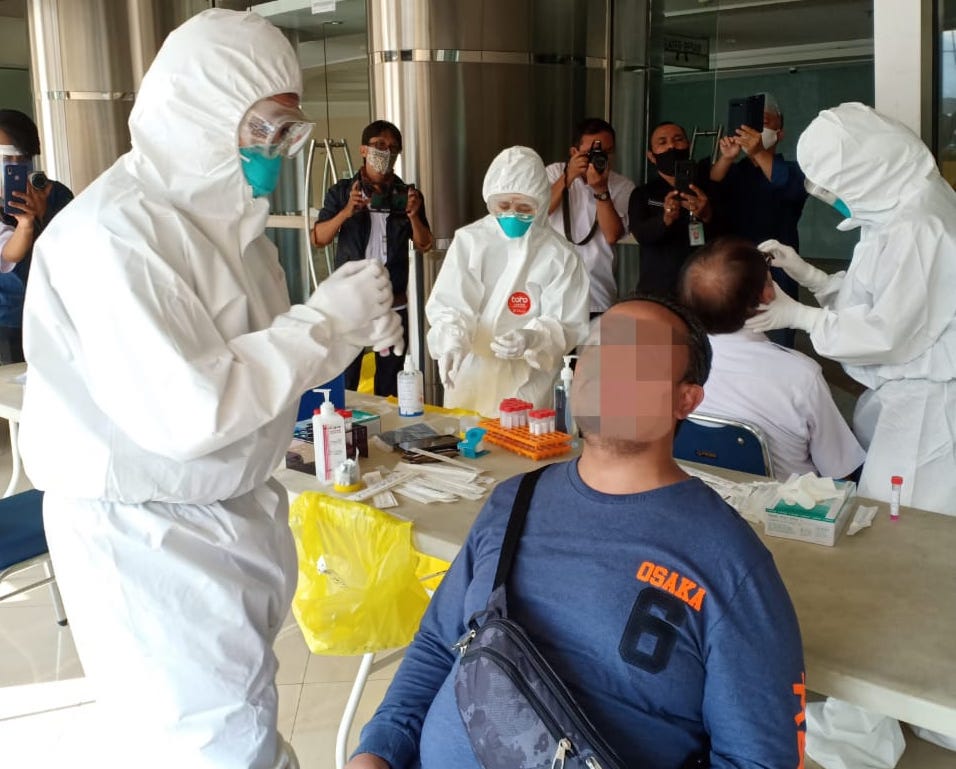

The job is a daily grind, and an uncomfortable one at that. Every morning, Aulia and her colleagues equip themselves with full protective gear, including hazmat suits, face shields, face masks, and gloves.

In hot and humid Jakarta, you may as well be working in a sauna.

“It’s pretty hot to wear when tracing cases in the field,” Aulia said, adding that being drenched in sweat constitutes a new normal for her.

Aulia and her colleagues usually get back to the office at around noon before they all have to take mandatory showers.

But Aulia’s day doesn’t end there, as she still has to deal with piles of documents and entering data she gathered from the field, as well as cross checking her work with reports from other agencies.

“There has always been a massive data load, from many agencies and institutions,” said Aulia.

Compiled data and reports are crucial for the government’s efforts to stop the spread of the coronavirus.

As such, the role of tracers is arguably at least as important as their medical worker colleagues in hospitals.

Fiena Fithriah, head of South Jakarta administration’s division for disease control and prevention, said field reports collected by the tracers are crucial tools to analyze infection patterns and determine health policies.

“Without the data that have been collected by the tracers, the jobs of health workers would be meaningless. So, actually, we are connected,” she said.

Dealing with rejection

Not everybody appreciates being tracked down by epidemiologists — understandably so given the fear and stigma surrounding the novel coronavirus, especially in the early days of the outbreak.

Abimanyu Soeriawidjaja, chief epidemiology investigator at a Puskesmas in Penjaringan, North Jakarta, knows all too well about rejection.

“When they hear that we’re from the health agency, they just hang up the phone,” Abi told Coconuts, referring to the number of times his team failed to carry out preliminary tracing by phone.

“They also don’t open their doors [when we visit their homes].”

For Fiena, who’s had to trace to elite South Jakarta neighborhoods where some of the nation’s most prominent figures live, a respectful approach is necessary.

“But above all, the key to success is to listen to them [air their grievances] before we conduct the interview,” she said.

Epidemiologists also have to supervise patients who self-isolate, most of whom are asymptomatic. It’s their carefree attitude that adds another element of difficulty to case tracing in Jakarta.

“Sometimes they just wander around like everything is okay,” Abi said.

In such cases, case tracers recommend reckless patients for hospital isolation. Any pushback from patients as they’re transported to a medical facility would result in intervention from the Public Order Agency (Satpol PP) or even military personnel.

A never-ending job

The burden of case tracing has gotten heavier as the months rolled by. With Jakarta under increasing political pressure due to its status as the province with the highest COVID-19 caseload, case tracing has turned into a more proactive task.

To ramp up its testing numbers, the Jakarta administration has instructed all health centers throughout the capital to perform active case finding, which involves conducting PCR tests on residents in their respective districts.

“I was really overwhelmed. After the policy was introduced, the duty became unbearable, because I had to join in the active case finding and also process the data of the patients, ” she said.

Since July, Aulia’s superior has allowed her to remain behind her desk at the community clinic, in part for her mental and physical well-being. Now, she keeps busy compiling and processing patients’ data and coordinating test results with laboratories.

It’s still gruelling work, often involving her burning the midnight oil as she toiled behind her computer screen for hours each day.

One particular day was a total nightmare for Aulia, when an employee at her office tested positive for the coronavirus. All staff were tested in a day, and Aulia was tasked with entering the data.

“Can you imagine, 200 staff tested in one day. I got home at 10PM. I cried that night,” Aulia said.

But for Aulia and other case tracers, late nights are just one of many sacrifices they have made during this pandemic. This job is, after all, their calling, and they may have to brave even harder days ahead as Jakarta loosens its restrictions and the number of cases continue to rise at an alarming rate.

Also Read — For Jakarta’s informal workers, the pandemic brings more uncertainty than ever for the future