On October 27, 2021, a female student entered the office of Syafri Harto, the dean of the political science school at Indonesia’s Universitas Riau in Pekanbaru, and her thesis supervisor. She said she was stunned when Syafri started flirting with her, gesturing and saying “I love you,” before eventually putting his hands on her shoulder. He then allegedly kissed her cheeks and asked her to kiss his lips. She said she pushed him away and left the room.

She asked the school’s head and secretary to assign her to a different thesis supervisor but said the two men dismissed her story, saying that it was “a small matter” and asked her to just meet with Syafri. They also advised her to remain silent about her accusation because it might “break up Syafri’s marriage.” She spent a week pushing back against the school. Meanwhile, Syafri, who had learned about her complaint from the lecturers, texted her, writing that the incident was “a father-and-daughter thing”.

On November 4, she reported the case to her student union, the International Relations Students’ Corps (Komahi). The group recorded her story and posted a 13-minute video on their Instagram. It went viral in Indonesia, prompting the Ministry of Education and Culture to send inspectors to visit the campus and the police to investigate Syafri.

Syafri denied the kissing accusation and filed a defamation suit against both the student and Komahi, seeking financial damages of IDR10 billion (US$700,000). Hundreds of students organized protests on the school’s campus to demand that university officials set up a task force on sexual violence.

This case is sadly one of many on university campuses across Indonesia. Most such cases have ended up with negotiated “peace settlements” that fall far short of providing justice to victims, who feel powerless against senior staff and university officials. Reports have emerged in Indonesian media about lecturers or senior students harassing, assaulting, and raping female students. The despair of victims who feel unable to seek justice is reflected in the viral hashtags accompanying the issue, which include #NamaBaikKampus (for the sake of the campus’ good name).

Last November, Education and Culture Minister Nadiem Makarim declared that sexual violence on Indonesian campuses was “a critical emergency.” Makarim had signed a regulation two months earlier to set up working units on campuses to deal with sexual harassment, attacks, and violence.

The regulation defines 20 prohibited acts as types of sexual violence, including verbal, non-physical, and online actions. It requires each campus to set up a task force with a majority of women members that includes both lecturers and students.

Makarim cited a 2020 Education and Culture Ministry survey that found that 77 percent of Indonesian lecturers believed that sexual violence had taken place on their respective campuses and that 63 percent of them did not report the cases to campus officials.

Religious Affairs Minister Yaqut Cholil Quomas called the regulation “revolutionary” compared to the typically “stagnant” policies surrounding sexual offenses. He also affirmed that the Religious Affairs Ministry, which is in charge of Islamic universities and schools, fully supports this new regulation, asking Islamic universities to set up similar task forces on their campuses.

But Makarim and Yaqut’s efforts faced a backlash from conservative Muslim groups. Fauzi Bahar — a politician from Padang, West Sumatra, who heads a local group called Lembaga Kerapatan Adat Alam Minangkabau — filed a petition at the Supreme Court seeking to have the decree abolished.

The same organization successfully challenged another Education and Culture Ministry regulation in February 2021 that permitted schoolgirls and female teachers to freely choose their clothes. In May 2021, the Supreme Court ruled that Muslim girls from grades 1 to 12 in state schools have no right to choose — they must wear a jilbab (an article of Muslim apparel, widely known as hijab in English, that covers the head, neck, and chest).

In Ambon, Lintas, a campus magazine, published a March 2022 report about 32 students who had been sexually assaulted between 2015 and 2021 at the Islamic State Institute. Instead of investigating the allegations, the campus decided to close down the Lintas newsroom, seizing equipment and closing the office.

Back in Pekanbaru, the university eventually set up an investigative unit and prosecutors arrested Syafri Harto on January 17, 2022, charging him with “sexual molestation.” Syafri’s trial featured 16 witnesses including the student herself, Syafri’s secretary, the two lecturers, the student’s co-worker and aunt, as well as three expert witnesses. A psychologist testified that the student’s story was consistent, and that she was traumatized.

Syafri denied that he gestured “I love you” to the student or kissed her, but admitted putting his hands on her shoulder.

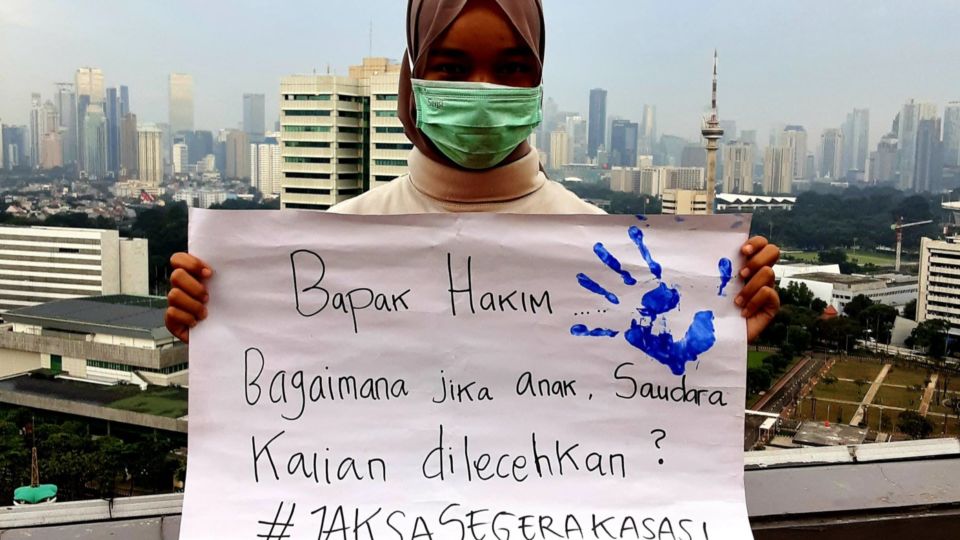

On March 30, the panel of three male judges found Syafri not guilty, determining that “a single witness is not a witness.” Dozens of Komahi members, both men and women, expressed shock at the verdict and reacted in court with sobbing and expressions of anger toward Indonesia’s legal system.

The court’s handling of the case showed a lack of gender sensitivity. A blanket rule that a case cannot stand based on a single witness, regardless of the witness’ credibility and other facts in evidence, would block many survivors of sexual violence from ever obtaining justice. The prosecutors plan to appeal the case before the Supreme Court in Jakarta. The small number of women on the Supreme Court, which features six female judges out of a total of 51. makes it quite possible that not a single female judge will be on the three-judge panel that hears the appeal.

The Indonesian government must urgently recognize and address the widespread cases of sexual harassment and assaults against female students taking place in universities across the country. Women’s lives and their access to education will continue to be deeply impaired so long as lecturers and administrators can engage in such abuses with impunity.

Andreas Harsono is a senior researcher at Human Rights Watch. You can find him on Twitter here.