There was a great deal of disbelief and plenty of bemusement on our social media channels this week when we wrote that DC Comics had lost a lawsuit against an Indonesian food and beverage company that’s been using Superman to hawk cookies.

From the outside looking in — and for fans of intellectual property in general — the ruling appeared inexplicable. But in Indonesia, it’s actually pretty well-established at this point that being the creator of a brand, even a globally recognized one that’s been in use for decades, means approximately jack squat.

As long as somebody registers the brand/logo/character before the original owner, no matter how well known it is, the Indonesian legal system is likely to side with the former.

Don’t believe us? Here for your reading pleasure are a handful of the most infamous cases of globally renowned companies losing court battles for the right to their own products in Indonesia in recent years — starting with the Man of Steel.

Superman

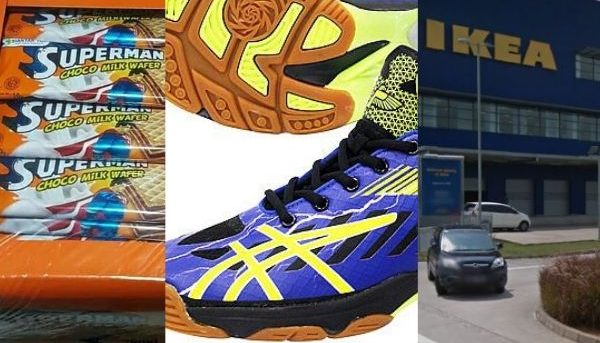

Millennials who grew up in Indonesia are likely to be familiar with the Superman chocolate wafer cookies, which have been sold (often in kiosks near schools) since the ‘90s.

PT Marxing Fam Maktur, a food and beverage company based in Surabaya, currently holds the right to use the Superman image on snack products here, a fact DC Comics was completely unaware of.

Until recently, that is.

When DC decided to register the Superman trademark in Indonesia in 2017, the comic publisher was more than a little surprised to find there was already an existing trademark on their iconic superhero.

In April 2018, DC filed a lawsuit with the Central Jakarta Commercial Court against Marxing, but the former lost because the latter had registered Superman as a trademark in Indonesia first. Indonesia’s Supreme Court then upheld that decision, saying that the plaintiff’s lawsuit was “obscure”.

Never mind that DC (then Action Comics) introduced Superman to the world in 1938, Marxing, which registered the trademark here in 1993, argued that as their use of the Superman image was limited to food products, it did not piggyback on the superhero’s popularity. This despite the fact that they not only used the name but copied the likeness of the character and even the iconic “Superman” font for their packaging.

In their lawsuit, DC said Marxing had acted in bad faith in registering the Superman trademark without their permission. But, in the eyes of the Indonesian legal system, DC did not even have a case.

IKEA

Swedish furniture giant IKEA opened its first — and so far only — store in Tangerang in 2014. A year before that, PT Ratania Khatulistiwa, a rattan furniture company in Surabaya, registered the trademark IKEA name, claiming it was an acronym for “Intan Khatulistiwa Esa Abadi.” Cheeky.

Curiously, and unlike DC, IKEA (the real one) actually did trademark its name, first in 2006, then again in 2010. But by the time our rascally rattan seller Ratania made a play for the iconic trademark, IKEA had not actively used the name in three years, meaning it was up for grabs under Indonesian law.

Armed with that legal claim, Ratania sued IKEA over the name and won at the district level. In 2016, Ratania won again after IKEA appealed to the Supreme Court, which ordered the Swedish company to stop using the name and logo they created and made famous.

In the end, while losing in court, IKEA still came into the market using their trademark (well, not here) blue and yellow signage, meaning it’s likely they quietly worked out a deal with Ratania. Adding weight to that theory? The fact that Ratania, despite holding the copyright, doesn’t brand itself as IKEA.

Onitsuka Tiger/Asics

Japanese sports apparel company Asics, which owns the Onitsuka Tiger brand, has a copycat of their famous sports footwear in Indonesia — one that is protected by law.

Footwear company Professional produces shoes that feature a logo indistinguishable from the one that adorns Asics and Onitsuka shoes. In 2010, Asics sued the founders of Professional — Jakarta citizens Theng Tjhing Djie and Liog Hian Fa — for IDR6 billion (now US$416,000) for using the logo without their permission.

The Central Jakarta Commercial Court rejected the lawsuit on the grounds that Djie and Fa had registered the logo in 1994, meaning they had the right to use it in their products in Indonesia. Asics also lost a subsequent appeal to the Supreme Court in 2015.

Armed with the globally recognizable logo, Djie and Fa said they sold 80,000 pairs of shoes between 2009 and 2012, raking in a profit of IDR4.8 billion.

Pierre Cardin

Even having a company named after its founder is no guarantee that its branding won’t be snapped up someone else, which is exactly what happened to fashion label Pierre Cardin in Indonesia.

While Pierre Cardin knock-offs are available the world over, here, they have official status. Like Asics, our local “Pierre Cardin” — created by Jakartan Alexander Satryo Wibowo — is protected by Indonesian law. And just as our local “IKEA” sells furniture, our Pierre Cardin sells fashion goods.

In 2015, Pierre Cardin, the French one, sued Satryo Wibowo — who had snapped up the trademark in 1987 after other local entrepreneurs registered the brand in 1977 — arguing that the latter shouldn’t have been able to trademark a name that had already been recognized worldwide for decades.

The Central Jakarta Commercial Court (surprise!) rejected the lawsuit, using the first-come-first-serve argument that has become the common thread in these intellectual property conflicts.

Unsurprisingly, the Supreme Court upheld the decision in 2018, though one of its three judges actually sided with the original Pierre Cardin.

Though Pierre Cardin is unable to file another lawsuit on the matter, the government gave a small consolation to the French fashion brand, allowing it to coexist alongside the Indonesian Pierre Cardin. To differentiate the two (beyond the major price differential) Indonesian Pierre Cardin goods must feature a disclaimer saying “Product by PT Gudang Rejeki” on the labels of their products. So they’ve got that going for them.