By Rafiqa Qurrata A’yun, University of Indonesia

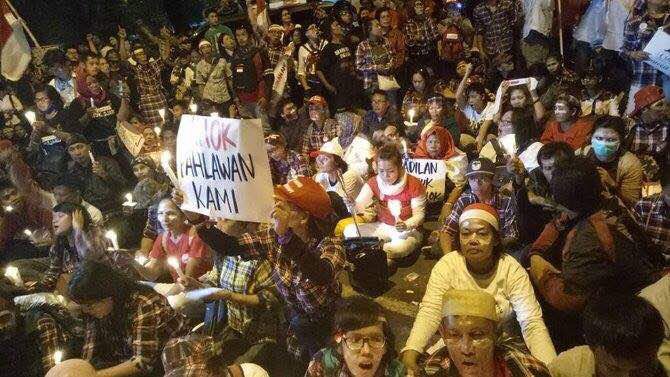

Across Indonesian cities and abroad, candlelight vigils have been held in support of Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, the Chinese-Christian former governor of the capital Jakarta. He was recently sentenced to two years in prison for blasphemy for insulting Islam.

Purnama, popularly known as Ahok, is one of many people jailed under this controversial law. In the last 15 years more than 100 people have been convicted of blasphemy and jailed in Indonesia.

Human rights activists have argued that the laws discriminate against religious minorities and promote religious intolerance.

Ahok, a brash politician who enjoyed high popularity among Jakarta’s people, became embroiled in the blasphemy case after an edited video of him criticizing opponents who use a verse in the Quran to dissuade people from voting for a non-Muslim went viral.

The blasphemy case factored in Ahok’s loss in the recent Jakarta gubernatorial election. His opponents exploited the brewing religious and racial sentiments against the double-minority Ahok. They aligned themselves with hardline Islamic groups that organized a series of massive rallies demanding he be jailed.

Although Ahok lost the race, he received 42.05% of the vote, or 2,351,141 people. The size of his vote presents an opportunity to gather support to challenge the blasphemy law.

It’s not yet clear whether Ahok’s supporters will move to challenge the problematic blasphemy law or not. So far, his supporters are focusing on Ahok’s innocence. The sentence was harsher than prosecutors’ demand of two years’ probation. Some of Ahok’s supporters rally behind him not to protest the blasphemy law, but to save their idol.

In fact, Ahok’s supporters are using the same blasphemy law to report the firebrand Muslim cleric Rizieq Shihab, leader of the Islamic vigilante group Islamic Defenders Front (FPI), which organized protests against Ahok.

Blasphemy law

Indonesia’s first president, Sukarno, introduced the blasphemy ban by decree in 1965, when communists, Islamists and the military were competing for power.

His successor, Soeharto, who rose to power after ordering the rooting out of communists in Indonesia, got the parliament to promote the decree into law in 1969 and insert anti-blasphemy clauses into the penal code.

Blasphemy charges have been laid against people considered to be spreading unorthodox interpretations of religion. Ahmadis have been banned from practicing their faith in public and from spreading their belief using this law. In 2012, a Shiite cleric from Madura was imprisoned.

Al-Qiyadah Al-Islamiyah, a syncretist sect, was declared heretical in 2008. Its leader, Ahmad Musaddeq, was sentenced to four years’ jail. He was convicted again on blasphemy and treason charges in 2017 because of his leadership of the Gafatar, which was presented as a reincarnation of Al-Qiyadah.

The law has also been used to punish people deemed to have insulted religion. Even a poll result could put one in jail.

Arswendo Atmowiloto, the Christian chief editor of a weekly tabloid, served five years in prison. His poll had listed the Prophet Muhammad as the 11th-most-revered figure among his tabloid’s readers – behind Soeharto, who took first place.

Seeing how the blasphemy law has put people behind bars for matters that are highly subjective and private, human rights defenders have twice requested, without success, that the law be reviewed.

Indonesia’s Constitutional Court maintained that the law was needed to prevent instability arising from polarization and violence. Criminalizing blasphemy was believed to deter people from taking the law into their own hands when they felt their religion was being insulted or threatened by unorthodox interpretations.

But it is impossible to try blasphemy without the judiciary being influenced by political and social pressure. Mob protests have prompted many blasphemy cases.

Large-scale riots after a blasphemy trial in 1996 in Situbondo, East Java, also demonstrate the ineffectiveness of the blasphemy law in maintaining public order.

The judges sentenced a man named Saleh to the maximum five-year jail term for insulting the head of a local Islamic boarding school. The mob, which wanted the death penalty for Saleh, was not satisfied. They burned down buildings owned by Christian-Chinese businesses, schools and 25 churches, killing five people.

Remove or revise?

Despite the clear problems inherent in the law, it will be difficult to petition the Constitutional Court once again to review it.

The court is unable to review any material substance (paragraphs, articles and/or a section of a law) that has already been subjected to review.

The first petition (2009) used rights issues as an argument to cancel the law. The second (2012) focused on Islam in Indonesian history and tradition.

In its 2010 ruling on the first petition, the Constitutional Court encouraged the petitioners to appeal for a revision, instead of revoking the law.

Tough middle ground

Considering the dominance of right-wing politics in Indonesia, it may be tough to amend the law through the parliament. Politicians, even those from the ruling party who supported Ahok’s candidacy as governor, might hesitate to tackle sensitive religious issues.

But unless human rights lawyers can find a different argument from the past petitions, revising the blasphemy law through legislative processes so as to not impinge on people’s religious freedom might be the most possible path.

Consistent pressure from the public will be needed to convince legislators that the law should be revised.

It’s not impossible if enough people stand up for the right of all people to individual freedoms. But this will need more than flowers, balloons, candles or hashtags.

Rafiqa Qurrata A’yun, Lecturer, Department of Criminal Law, Faculty of Law, University of Indonesia

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

![]()