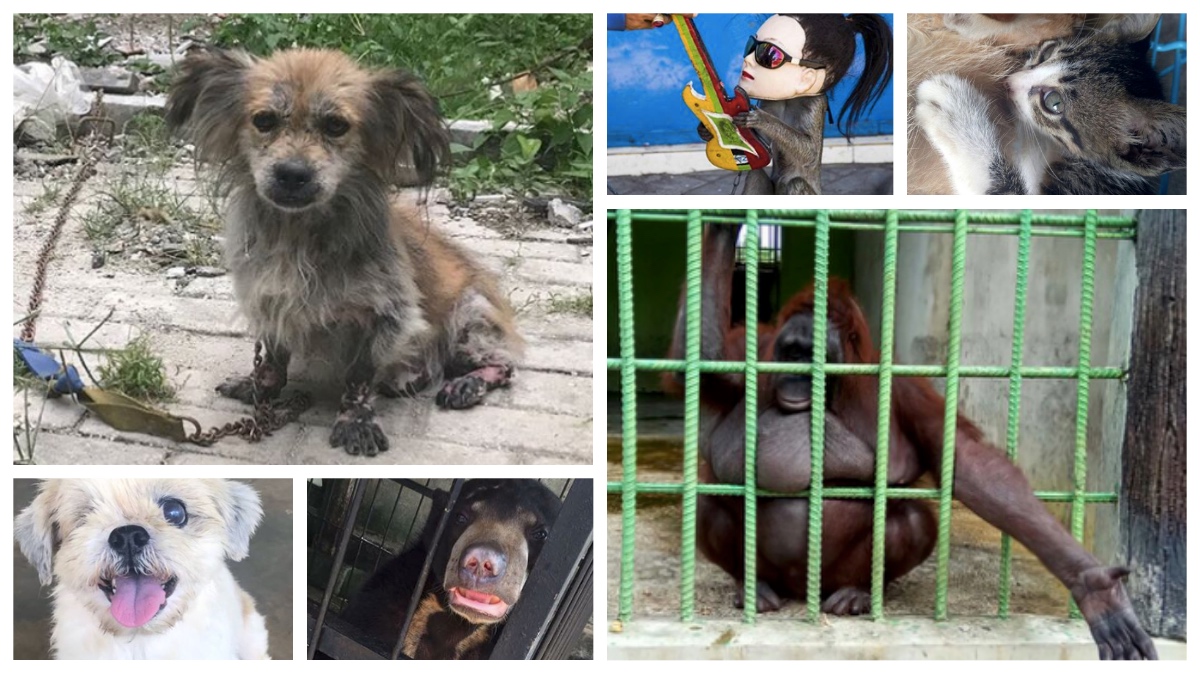

Like many dogs, Ella, an adorable little Shih Tzu, kept her distance from me the moment we met. But, in a matter of minutes, the little pooch and I were well acquainted, and soon I was able to pet her as if we had long been best buds.

It was hard to tell from her friendly personality, but Ella had experienced unimaginable abuse at the hands of her previous owner — the kind of mistreatment that would be considered criminal in other countries. But in Indonesia, animal activists can rarely rely on the law or law enforcement to help them end such cruelty. To save abused creatures like Ella, they are forced to take matters into their own hands.

—

Indonesia is essentially lawless when it comes to protections for animals. Animal abuse — ranging from small cruelties toward domesticated animals to the illegal meat trade and poaching — is rampant and much of it is ignored by law enforcement.

Animal welfare activists have long called for tougher laws and better enforcement to prevent animal cruelty. At the same time, this relative handful of people, who are often the only ones standing between animals and harm from humans, must make do with little, if any, legal backing.

In their 10 years of existence, the Jakarta Animal Aid Network (JAAN), one of the country’s most prominent animal welfare groups, has rescued hundreds of animals from the clutches of cruelty. It’s a thankless, often risky job, and rarely do they seek the help of police.

Few animal welfare groups do. One of the main reasons is that Article 302 of the KUHP (Penal Code) — the go-to law for general animal abuse — only stipulates three months’ imprisonment or a fine of IDR4,500 (about US$0.31) for those convicted of animal cruelty. In the case that the animal suffers grave injuries or death from the abuse, a maximum prison sentence of nine months and, strangely, a smaller fine of IDR300 apply.

Those fines might have meant something in the Dutch colonial era, when the KUHP was originally drawn up, but even the bigger fine would only buy you a small bag of peanuts these days.

In her South Jakarta home, JAAN cofounder Natalie Stewart sat down with me to explain why their rescue struggles rarely involve law enforcement. The animal welfare group, just like every other one in the country, are mostly on their own in their quest to save animals.

Ella and Little

Hovering curiously around our conversation were Ella and her canine pal Little, a small white poodle. It’s a testament to how much love and care JAAN give to their rescued animals that that the pair grew to be such cheerful dogs, despite their horrific pasts.

Little, Natalie tells me, was found in a trash heap, where he had lived for weeks, starving to death. When he was rescued, he was scabby and had lost all his fur. Nowadays, he is JAAN’s de facto mascot, coming to all of their school showings, letting hundreds of kids pet him. That day, the kid in me was delighted by having a brief opportunity to play with him.

Ella, on the other hand, was adopted but treated so badly for more than a year that that she was living in her own filth when JAAN rescued her from her irresponsible previous owner.

As is the case with almost all animal rescues performed by JAAN, the authorities were not present during Ella’s rescue. According to Natalie, there have only been one or two cases during JAAN’s entire existence in which Article 302 was invoked.

“We know that it will not have a positive result. It may get us the dog, eventually, but we can’t take every dog since we’re already at maximum capacity. What we need to do is educate the owners to improve the living standards of that animal,” Natalie said.

Education, with a threat

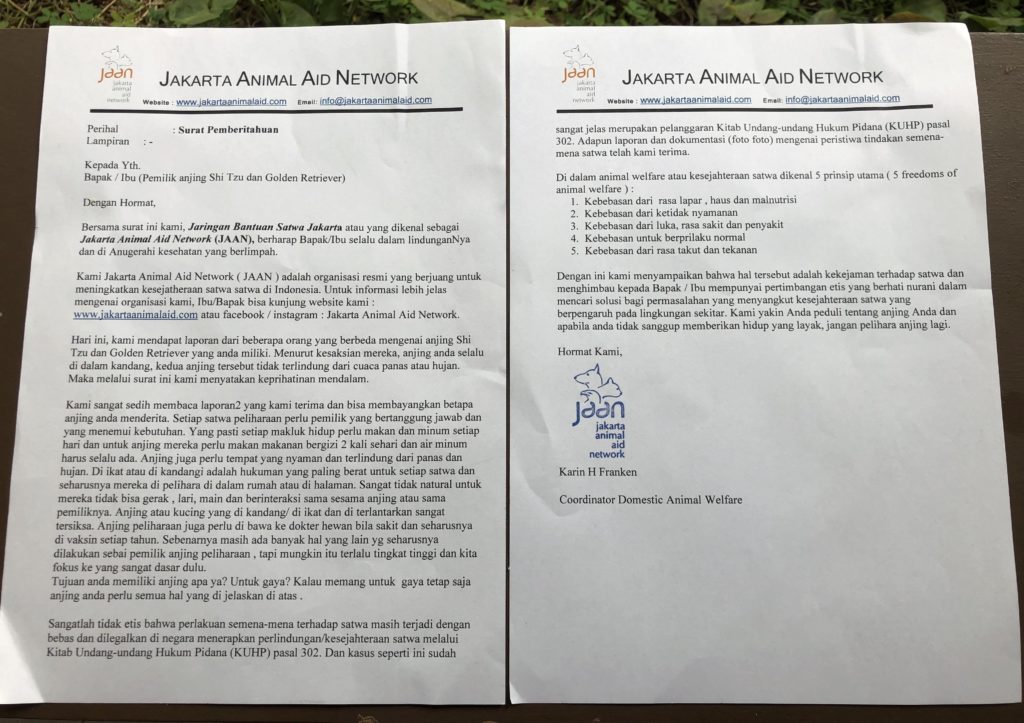

That’s not to say Article 302 has no use at all for JAAN, though not in the direct sense. When JAAN gets a report about animal mistreatment, often from concerned neighbors, they send a letter to the animal’s owner appealing for more humane treatment of their animal and a reminder of possible jail time under Article 302.

“It’s kind of scary. The problem is we don’t have a police force that will come and enforce this law. But at least this will get people to think, ‘oh geez, I might be doing something wrong here and I could get in trouble,’” Natalie said.

It’s mostly a bluff, though. Often, the culprits were just unaware that caging their pets or leaving them outside constituted as cruelty, and they change their ways upon receiving the letter. The more stubborn ones end up giving up their animals to JAAN after a verbal threat of police involvement, which is just another bluff.

Doni Herdaru, founder of animal welfare group Animal Defenders Indonesia, has had many of his rescue stories go viral on social media and widely picked up by mainstream media. He also utilizes social media to shame and educate animal abusers — a tactic that has resulted in several public apologies. like a recent incident in which a man blew a cloud of vape smoke in a monkey’s face at a zoo.

Doni, too, is not a believer in the law.

“We always put forward persuasive means instead of repressive, such as using the law and its enforcement. Because the reality in Indonesia is, the law is not on the side of animals, even though the means [for enforcement] is there,” Doni said.

“We have on a few occasions reported animal cruelty to the authorities using [Article 302], but during the rescue, I thought it ended up being unnecessary and ineffective.”

The last monkey dance

In 2013, then-Jakarta Governor Joko “Jokowi” Widodo passed a regional bylaw banning topeng monyet — macaques being forced to dance by street buskers for the amusement of crowds, after years of exploitation. This was one of JAAN’s biggest legal victories to date regarding animal welfare after they heavily campaigned for its ban since 2009. By the time the bylaw was passed, JAAN was also closely involved with its enforcement.

Today, the practice of topeng monyet is practically nonexistent in the capital because animal welfare groups like JAAN have the legal justification to confiscate the exploited primates. That said, efforts to expand the ban nationally have bore little fruit, as not all regional leaders are as sympathetic towards the cause. Even in Jakarta’s satellite cities, which fall under other provinces, macaques are still being forced to dance.

The government, then, plays a huge role in the protection of animals. But, JAAN has little hope other officials would take action like Jokowi did when those in the government whose actual jobs are to protect the environment won’t do what the taxpayers are paying them for — at least not without a little under-the-table financial incentive.

“On the wildlife side, we do get action from the police to help us with confiscation of topeng monyet, which is illegal in Jakarta, and other things that are illegal. It also involves the Forestry Department, which is a huge, corrupt department in itself. If you’re not paying off these people to come and do their jobs, they’re not going to do it. We don’t have the money to get the police to come out for every single case,” Natalie said.

She added that Jokowi’s successor, Basuki “Ahok” Tjahaja Purnama, was also attentive to animal welfare, being a dog owner himself. Under his leadership, JAAN collaborated with the administration to launch animal welfare campaigns and education programs in schools.

But, since Ahok was succeeded by Governor Anies Baswedan last year, Natalie said it’s back to square one for JAAN in terms of lobbying the city administration. The current administration doesn’t seem to have animal welfare high on their agenda either (they even overturned a ban on horse carriages instituted by Ahok), and although this hasn’t blown up in the media yet, JAAN has seen topeng monyet seeping back into Jakarta and are fearful it will become prominent in the capital once more.

https://www.instagram.com/p/Bl5O7tFB75X/?hl=en&taken-by=jakartaanimalaidnetwork

Giving the law teeth

Enforcement issues aside, animal activists in Indonesia believe that introducing harsher punishment for animal cruelty is an important first step to fauna protection. The problem is, do lawmakers agree?

Wenni Adzkia , a researcher at the Indonesia Center for Environmental Law (ICEL), says there is a proposal to increase the punishment in Article 302 in a proposed revision to the KUHP (RKUHP). The proposed amendment, stipulated under Article 364, would see punishment for deliberate harm towards animals, including sexual relations with one, increased to a maximum of one year imprisonment or a maximum fine of IDR120 million (about US$8,280). Cruelty leading to heavy injuries or death of the animal would be punishable by up to one year and six months in prison or a maximum fine of IDR30 million.

It’s a huge improvement in terms of fines, even though the punishment for death is counter-intuitively still lower than for causing injury. But, like many other aspects of criminal law riding on passage of the RKUHP, we still don’t know when these new punishment will come into effect.

Even if the RKUHP is passed, judging from how little Article 302 has been enforced, Wenni isn’t confident that 364 will be any different.

Even in extreme cases that should constitute blatant animal abuse, culprits all too often manage to find legal or cultural justifications for continuing their cruelty.

For example, JAAN is attempting to stop the practice of traveling dolphin circuses that perform throughout Indonesia. Despite these circuses’ documented cruelty, including starving dolphins so they’ll be more compliant in performing tricks, keeping them in tiny chlorinated tanks, and even pulling out their teeth, JAAN and other animal activists have not had much luck shutting the circuses down as they claim their performances are “educational,” something the government backs up, giving them license to continue.

The dog meat trade is also a major concern for animal activists. Even though it has been outlawed in some regions in Indonesia, exposés have shown that in places where it is practiced like North Sulawesi, the dogs are brutally bludgeoned and sometimes even torched alive to prepare their meat for sale. Despite the outrage, the governor of North Sulawesi defended the practices, claiming they are not cruel.

“I assume that animal cruelty cases are rarely reported to the authorities. Even if they are reported, it probably wouldn’t be the law enforcers’ priority compared to cases of theft, murder, and other things that are deemed more concerning to the general public,” she said.

Please take a moment to learn about and support animal rescue groups like the Jakarta Animal Aid Network and Animal Defenders Indonesia. Your help can mean the difference between life and death for the city’s most vulnerable animals.

Also watch: