Residents of Indonesian city Palu in Central Sulawesi had little time to escape let alone react to a tsunami that hit hard on Friday evening, following a 7.5 earthquake.

The events were in quick succession: the quake’s epicenter was just about 50 miles north up the coast from Palu.

A tsunami warning was issued by Indonesia’s Meteorology, Climatology and Geophysics (BMKG) Agency, but quickly lifted about twenty minutes following the 7.5 earthquake, supposedly after the tsunami had already hit Palu.

The devastation wrought by the three-meter tsunami, which along with the earthquake has managed to kill over 800 and counting, has prompted questions over Indonesia’s ability to quickly and accurately predict tsunamis and generate warnings.

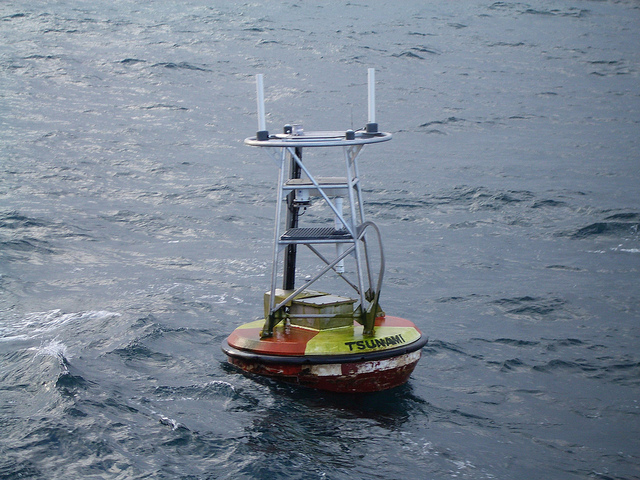

The country hasn’t had a functional tsunami detection buoy system, also known as deep-ocean assessment and reporting of tsunamis (DART), since 2012.

This was revealed by National Disaster Mitigation Agency (BNPB) spokesman Sutopo Purwo Nugroho at a press conference in Jakarta on Sunday. Sutopo pointed to Indonesia’s Meteorology, Climatology and Geophysics (BMKG) Agency for answers.

“Since 2012, there hasn’t been one operating, even though it’s needed for early warning. It can be asked to BMKG why from 2012 to now, it’s not there,” Sutopo said.

At the same press conference, Sutopo expressed frustration at budget constraints his agency is facing.

“Disaster funding continues to decline every year. The threat of disaster increases, the incidence of disaster increases, but BNPB’s budget actually decreases. This affects mitigation efforts. The installation of early warning tools is limited by a continuously reduced budget,” CNN Indonesia quoted Sutopo as saying.

In December 2017, Sutopo previously drew attention to the fact that Indonesia had a total of 22 buoy sensors scattered across its waters that were totally damaged, either stolen or vandalized.

Responding to Sutopo’s comments, head of BMKG Earthquake and Tsunami Center, Rahmat Triyono backed up the BNPB’s statement that the buoy system was out of service, but shifted the blame from BMKG.

“Yes, it doesn’t exist anymore and doesn’t support BMKG with data,” Rahmat told CNN Indonesia.

According to Rahmat, Indonesia installed buoys across multiple points throughout Indonesia following the devastating tsunami that hit Aceh in 2004, but those buoys were either lost or damaged.

“Because it’s in the open ocean, no one was watching them. In fact, they were all lost. Some lost from being taken by fishermen, or dragged away by ships,” Rahmat said.

“There was even one located in Muara Angke (fishing port in Java), because it was found by fishermen. Because there was GPS, it was detected. It was dismantled,” he added.

The institution responsible for procuring the buoys is the Agency for the Assessment and Application of Technology (BPPT), not BMKG claims Rahmat.

BPPT deputy of Natural Resources Development and Technology, Hammam Riza similarly singled out lack of resources as the main factor for lack of upkeep and attention paid to the buoys.

“So far, we have been very busy with post-earthquake handling efforts while anticipation has been very minimal, not even a priority,” Hammam told BBC Indonesia.

Which brings us to today.

BMKG is still able to carry out early detection functions without the buoys, since they use a system based on tsunami modeling, using seismographs, GPS, and tide gauges, but having them in place would increase their modeling’s accuracy, according to Dahmat.

“So, we get scenarios using tsunami modeling. At present, we have are around 18,000 tsunami models.

“But if we have incoming data from the buoys, the scenarios will be more accurate, because there would be observation data.”

As with any natural disaster, however, tsunami forecasting is an imperfect science and scientists can only begin to increase their accuracy as real life instances occur, providing more data. While an MIT Technology Review examination of the reliability of DART in 2011 has found that the system is flawed and has its limitations, the system could help Indonesia, Louise Comfort, a professor at the University of Pittsburgh graduate school told the New York Times.

The current system is too limited as is, says Dr. Comfort, who has been trying to help bring new tsunami sensors to Indonesia and has been discussing the project with the Indonesian government, planning to bring a system prototype to eastern Sumatra this month. Unfortunately, the project reached a stalemate amongst three Indonesian agencies.

“They couldn’t find a way to work together,” NYT quoted Comfort as saying.

“It’s heartbreaking when you know the technology is there,” she said. “Indonesia is on the Ring of Fire — tsunamis will happen again.”