One of Bali’s largest off-the-beaten-path attractions is not for everybody. Visitors to the 9-hectare site have to brave dirt, broken glass, as well as dense foliage and plenty of cobwebs. It’s a far cry from what its original developers had in mind, a 100-million-dollar Disneyland-style extravaganza of family-friendly entertainment.

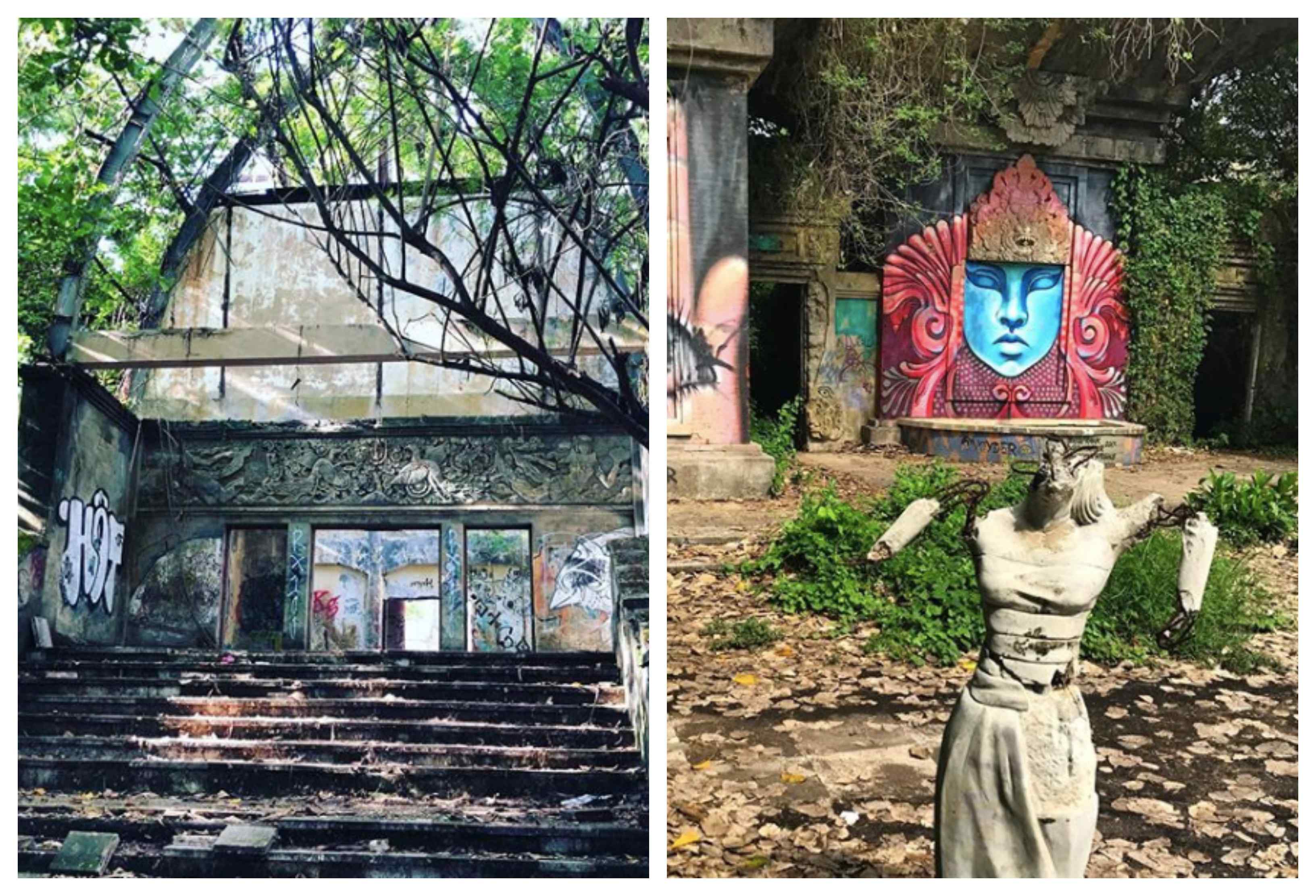

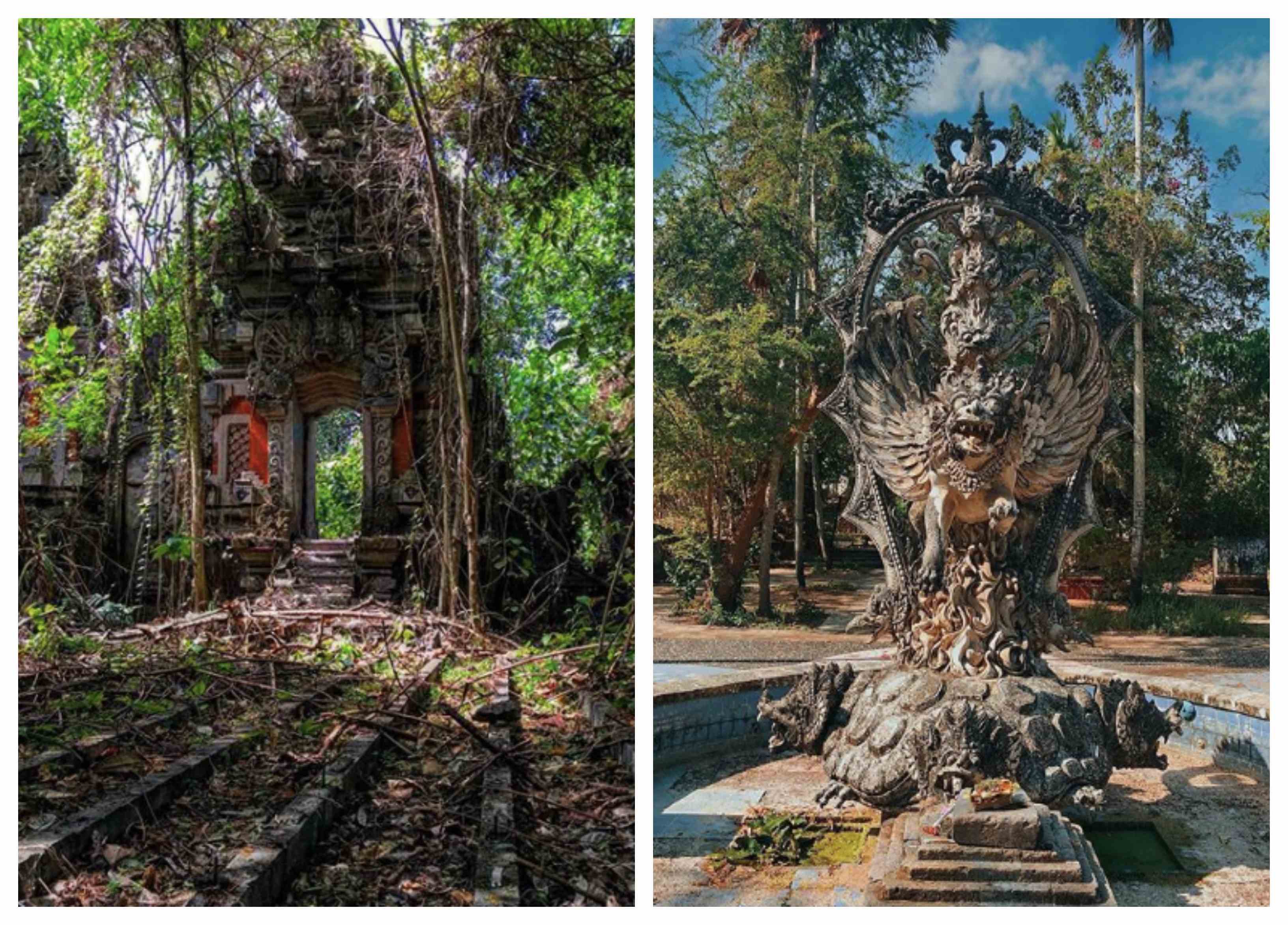

Today, the complex — known as Taman Festival Bali — is slowly being swallowed by the jungle, with vines creeping through the cracks in the walls of long-abandoned buildings and twisting through derelict game stands.

Despite the neglect, the area exudes an eerie charm that attracts a slew of graffiti artists, photographers and urban explorers. Earlier this year, the park was also the setting for Naskleng 13’s custom motorbike festival, which brought together over 700 participants and showcased around 200 modified bikes.

Set along Padang Galak beach, around a 20-minute drive north of Sanur, Taman Bali Festival is the result of a collaboration between the local government and a wealthy Indonesian investor. The expansive complex opened its doors in 1997, but the multi-million dollar dream was not meant to be, and the project folded in 2000.

There are several theories as to why the venture was not successful, but the most likely one is that Asia’s economic crisis, combined with an exodus of tourists concerned about reports of political unrest in Indonesia, took its toll on the amusement park. There are also some other, perhaps less believable, stories circulating the island. The most far-fetched being that the park’s 5-million laser equipment, meant to bring the night sky to life each night, was struck by lightning on Friday the 13th of March 1998. The incident was the final nail in the coffin of the flailing venture.

Don’t expect Taman Festival Bali to appear on most guesthouse attraction lists — many Balinese believe that abandoned sites are home to lost spirits — nor a queue at the front gate. All that remains at the entrance to the park are deserted ticket booths and a few abandoned cafeterias. A slew of self-proclaimed security guards stands at the ready to collect a 10,000 Rupiah entrance fee. As the facilities are no longer maintained, it is up to each visitor whether they want to hand over the cash, although the park’s so-called guardians may be insistent. Another alternative is to enter the park via a path from the beach — simply park at the end of the street, walk left along the beach, and then head inland.

The word is that the sprawling park was supposed to feature the world’s first entirely inverted roller coaster, a micro-brewery, Bali’s largest swimming pool, a man-made volcano rigged to erupt each evening, as well as the ill-fated laser hologram show. It is unclear to what extent the park was already completed when it closed for business, but rather than attracting throngs of tourists, the grounds fell into disrepair. According to a Wall Street Journal report published at the time, the mega complex was projected to attract 1200 visitors daily — but instead, it ended up drawing a mere 200 people on weekends.

It is enthralling to see just how quickly the surrounding jungle has reclaimed its territory. Dense foliage has crept into the derelict structures with partly collapsed roofs, some still sporting signs denoting their original purpose. Among them is the Turbo Theatre, which was meant to screen 3D films, and the now-crumbling faux volcano. Statues and ornamental stone figures, which once beautified the park’s courtyards, now stand broken and overtaken by vines. Many of the decrepit buildings are covered in graffiti — from crude tags to dazzling murals — making for some very snap-worthy moments. At the rear of the grounds, a labyrinth of narrow dirt trails meanders through bushes, connecting different areas of the park.

Visitors to the complex might wish to keep an eye out for what was supposed to be one of the park’s central attractions — the crocodile pit. According to an urban legend, when the park closed, the crocodiles were left in the park to fend for themselves. The locals would feed them live chickens, but when they eventually stopped, the crocodiles resorted to feasting on the park’s human visitors. A more plausible story is that some of the decrepit buildings have been overtaken by families of bats. Whatever the case, visitors to the abandoned site should have their wits about them, wear closed-toe shoes and bring plenty of bug spray.