Talk to someone for any length of time about life in Bali and it won’t be long before one of its 11,000 Hindu temples will have been name-dropped. Which can hardly come as a surprise in a country where every village is required by adat (customary law) to maintain at least three: a temple of origin, for the village, and finally, for the dead.

On top of that, almost every family compound has a sanggah (shrine) within it. So, with such a prodigious number of holy places scattered across the island, it’s important to know your udeng from your tedung and your wantilan from your jaba, so you know what’s going on. To get you pointed in the right direction, here’s an A-Z guide to help you decipher some of the more beguiling terms being bandied about.

Bale

Punctuating every temple’s courtyards are the bales. Each has a raised seating section, an alang-alang (grass-thatched) or tali duk (black palm fiber-thatched) roof, and often serves as a place for the gamelan orchestra to sit, a village rallying point, or simply a place of rest for over-stretched worshippers.

Bedogol

The Balinese name for the stone gate guardians (not to be confused with the Balinese village, Bedugul). You can choose any character from the Balinese pantheon to be a bedogol, though obviously the tougher the better. Their role is to balance any unequal forces trying to affect the temple or home, so most people choose Kala because he’s both the creator of light and a leader in the underworld.

Busana Agung

For the highest occasions such as marriage and teeth-filing, busana agung (literally meaning ‘big clothes’) is the most appropriate formal wear. Consisting of an udeng (headdress), umpal (scarf), kamben (wraparound), kris (dagger) and lots of jewelry for the topless man, women don golden earrings woven with flowers, giant headdresses, luscious ‘songket’ fabric and other bling-tastic items.

Busana Agung. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

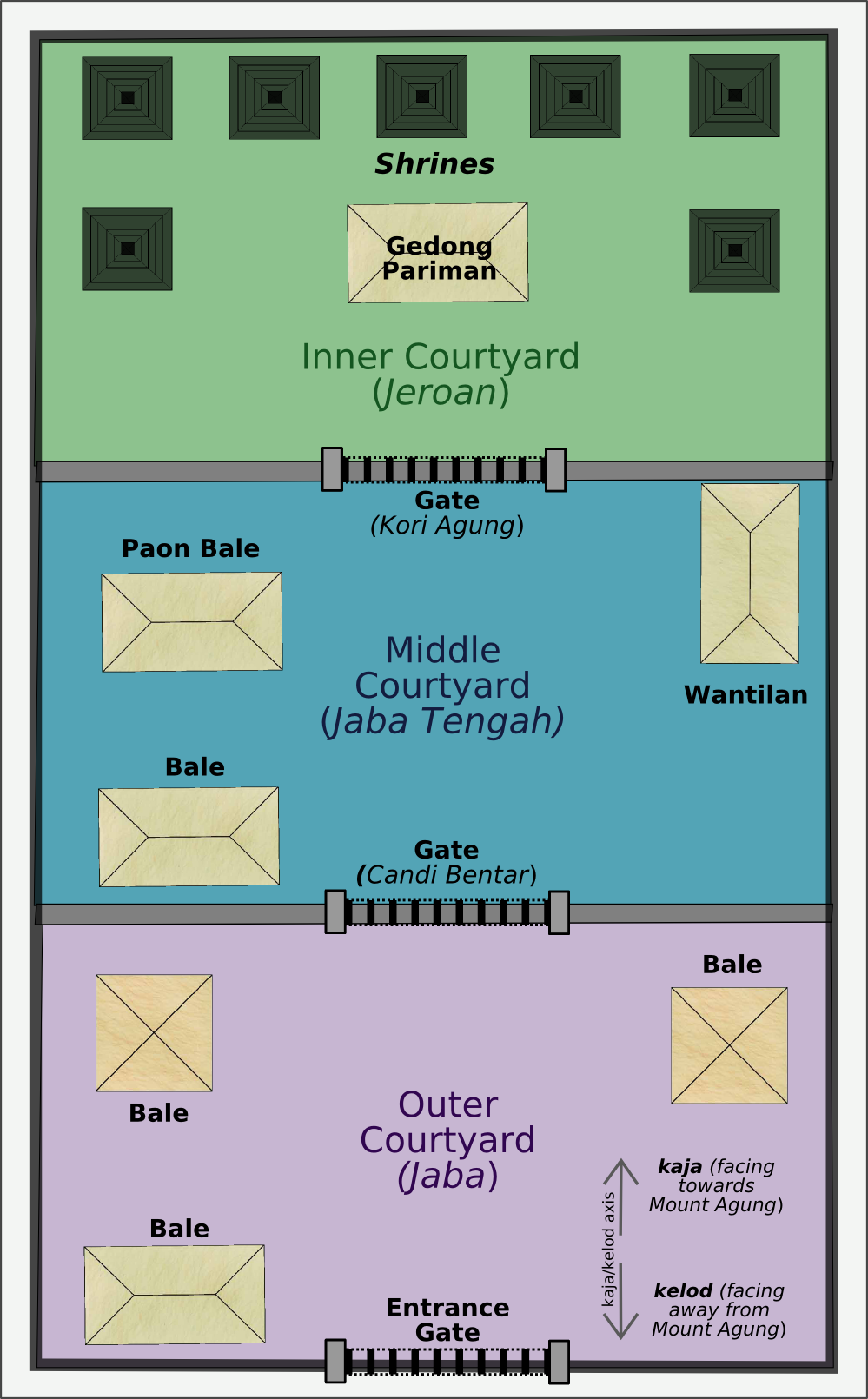

Candi Bentar

Taking the pious from the jaba (outer courtyard) to the jaba tengah (the central courtyard where daily offerings are prepared in an open pavilion known as a paon) this split (non-roofed) gate marks the spot where the realm of men meets that of the gods.

Entrance Gate

Always aligned to the kelod axis (facing away from Agung) this main entrance welcomes worshippers into the jaba.

Gedong Pariman

A fascinating pavilion in the jeroan (inner sanctuary), it’s always left empty so that the gods can visit during ceremonies.

Gedong Pesimpangan

A stone building with locked doors that’s dedicated to the local deity – usually the ancestor who founded the village or town.

A handy diagram showing the layout of a Balinese temple. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Jaba

The first courtyard, the jaba contains minor shrines and a space for dance performances. Non-Hindus are always allowed in this part of the temple, which also acts as a food stall during the bigger festivals.

Jeroan

The cockpit of holy energy at the back of the temple, never presume to enter the jeroan. Sometimes traditionally presented guests will gain permission, at other times not – it all depends on local customs, politics and ceremonial convention. Housing the major altars, it’s where the more serious rituals and prayers take place. Usually the biggest and best shrine will be the padmasana, the lofty lotus throne of the supreme deity, Sanghyang Widi Wasa (All-in-One).

Kahyangan jagat

The names and numbers (6-9) of the directional temples are almost always disputed (with variations by region) but what’s not up for debate is their role. Placed at the strategic spiritual points of Bali, they are fated to be the island’s first line of defense when it comes to attacks from the dark forces beyond. The usual canon includes the mother temple of Besakih on the slopes of Agung, Tanah Lot and Uluwatu in the south, as well as several others by the sea or on broken high ground.

Mandala

These are the spatial rules that govern Balinese architecture. Roughly divisible into two kinds: tri (from outer to inner sanctity) and sanga (the associations of cardinal points with gods), everything is devoted to a form of spiritual hierarchy.

Meru

The meru are the distinctive towers that rise from every temple. One-roofed shrines are dedicated to Mount Batur, three-roofed shrines to Mount Agung, and the tallest eleven-roofed ones to Sanghyang Widi Wasa (the supreme deity, the all-in-one god).

Photo: Flickr

Pedanda

High priests, the pedanda are outnumbered by the indigenous temple priests and balian (healers) roughly 20 to 1. Only a Brahman (one of the priestly class) can gain this office and all of them claim lineage from Wau Rauh, the most famous of the high priests in the Majapahit Empire (1293-1500). Often considered the highest position a person could ever hope to occupy, nevertheless some who’ve reached it complain that their lives are governed by too many rules and continually monitored.

Poleng

You’ll find the black and white saput poleng (two-colored cloth) all over Bali, in the form of parasol, sarongs, wrapped around trees, adorning people’s cars, and so on and so forth. Its checkered black, white and grayness is considered somewhat sacred by Balinese and symbolizes harmony between opposites, good and bad.

Pura

The Balinese name for a temple, it’s Sanskirt for ‘walled city’, which is exactly what it looks like.

Tedung

An umbrella, made of bamboo and banded together with decorative threads, that people hold in ceremonial processions, they come in several different colors with red symbolizing Brahma, black Vishnu, and white or yellow for Siva, the primal soul of the universe.

Wantilan

Located in the jaba tengah and used as the primary meeting hall, the wantilan is a good space for practicing (or watching) any kind of Balinese dance, from Gambuh to Pendent, and is, for many, the first obvious stop at any temple.