For the first eight years of her life, Nyoman Rasthi Asih was a girl without a language.

Born deaf into a family of hearing people, Asih had no way of communicating with her parents and two older siblings. She was prone to emotional outbursts, frustrated to the point of tears that she could neither express herself nor understand what was being said to her.

Asih didn’t go to primary school at age 6, the typical school-going age for kids in Indonesia. The elementary school in her rural village, located in one of Bali’s poorest areas, lacked the capacity to educate her.

With no interpreter at the school, there didn’t seem to be a point, her family thought — a justification common amongst families with disabled children in Indonesia. So, Asih stayed home and continued to feel isolated.

Everything changed when her mother learned that the “inclusive school” in village of Bengkala, just 12 kilometers from their village, would allow her daughter to enroll and better yet, teach her sign language.

That was three years ago.

Asih now knows how to read and write in Indonesian and, most significantly, has picked up “Kata Kolok,” a sign language used nowhere else in the world.

The village

Located in Bali’s northernmost regency, Buleleng, Bengkala Village is about a three-hour drive on a good day from the island’s Ngurah Rai Airport, 71 kilometers to the south.

While far from where most of the island’s tourism is concentrated, Bengkala has slowly developed its own steady stream of visitors piqued by curiosity surrounding its famous moniker: the deaf village.

While just one percent of the village’s population is completely deaf, Bengkala has earned its nickname thanks to its active community center of deaf residents and an “inclusive” elementary school with teachers who can use sign language.

“Kata Kolok,” the unique sign-language dialect that changed Asih’s life, was developed there over the course of seven generations and translates literally to “words of the deaf.”

There are hundreds of types of sign languages used around the world, and a number of countries employ more than one. Indonesia has two: BISINDO and SIBI. But Bengkala’s Kata Kolok, which developed organically from intuitive signing, is completely different, unintelligible to speakers of BISINDO and SIBI.

Simply put, there are literally no other villages like Bengkala in Bali.

The most up-to-date records identify 33 of the village’s 3,003 residents as deaf, local community leader Ketut Kanta told Coconuts Bali on a recent visit to the village.

That’s nearly double the global average estimated by the World Health Organization, which estimates five out of every 1,000 children worldwide are either born with hearing loss, or acquire it soon after birth.

That disproportionate deaf-to-hearing ratio has been attributed to a recessive gene, DFNB3, which has been the subject of studies by DNA researchers from Indonesia’s University of Gajah Madah and the University of Michigan in the US.

Basically, as carriers of the gene concentrated in this one geographic area, congenital deafness was passed down through successive generations. The same recessive gene has also been studied in the Okara district of Pakistan.

Back to Asih

Asih is confident for her age, has both deaf and hearing friends who can sign, and enjoys the same things most 11-year-olds do: playing games and watching TV. She also knows how to lay the charm on thick when mom’s watching.

“My favorite thing to do is helping my mother in her warung,” Asih signed innocently, as Ketut Kanta interpreted for us and her bemused mother looked on.

Asih is one of the village’s non-hearing population who were not born in Bengkala but instead moved there to take advantage of its growing number of services and deaf-friendly culture.

While it’s impossible without genetic testing to say if her deafness is due to DFNB3, there’s no arguing that her life has improved drastically since she began studying at the school in Bengkala. The school is a microcosm of the village: not all students can sign, though many can, just as many hearing residents in town know Kata Kolok.

Asih’s parents have learned to sign, too, taking lessons over the years with teachers from the elementary school, sometimes through video chat calls.

But, that doesn’t mean she has escaped the burdens of discrimination and stigma that inevitably come with being disabled.

Her parents have proven themselves incredibly supportive and committed to their daughter’s success, but the same can’t be said of some of their neighbors and extended family.

Asih’s birth was considered a curse by her family, her mother, Zeni Bayu, told us on a Friday afternoon outside her daughter’s classroom in Bengkala.

“My husband’s family blamed it on me and said it’s a curse. They bully me.

“There’s nothing I can do. I don’t say anything back, I just take it in silence,” she said, her voice quivering as she gently wiped the corners of her eyes.

Some neighbors told their children not to play with Asih, she told us.

The bell had just rung, dismissing class for the weekend, and Asih, dressed in a bright pink kebaya and unable to sit still, was visibly ready to go home, as her classmates spilled out into the hallway, down the hill, and out through the school’s gates.

It became crystal clear just how well-adjusted and confident Asih is as she signed rapidly to Kanta, asking him when it was time to go, cracking jokes, laughing, and letting out breathy exclamations that were almost like whispers. Watching her, it’s hard to imagine she only first began communicating with the world just three years ago.

A tourist attraction

While Bali is known best for its temples, resorts, beaches and food, Bengkala’s growing reputation as a cultural curiosity of sorts has given it a new identity: tourist attraction.

Five minutes’ drive from Asih’s school is the Bengkala Community Center, an open-air town-hall structure. Built with donations from the local government and Indonesian state-owned oil and gas holding company Pertamina, the town hall has a few rooms for deaf villagers and their family members, who live on site.

There, they operate a market where they sell hand-woven fabric and homemade snacks. It’s also where residents practice “kolok janger,” or “the dance of the deaf.”

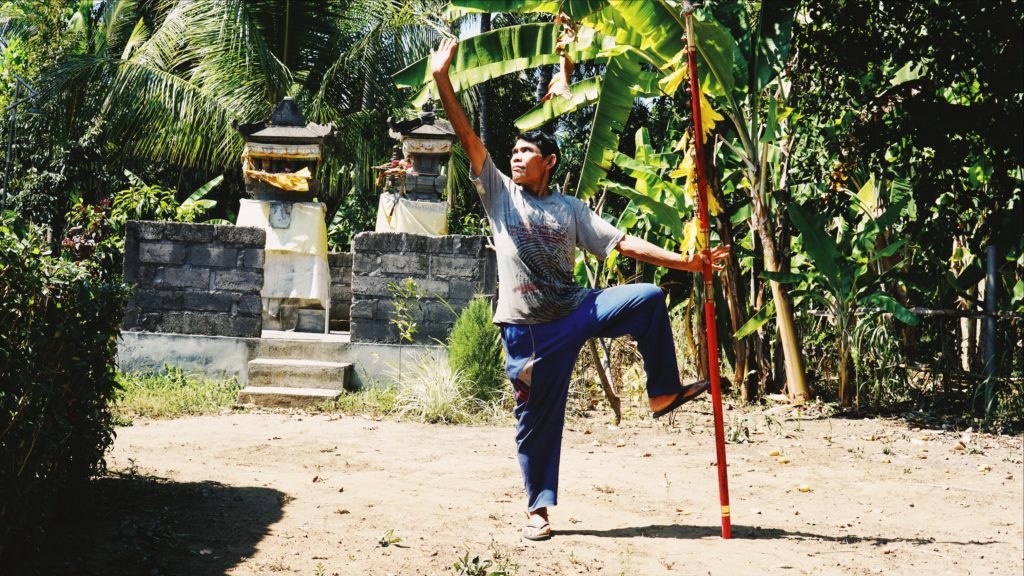

“Tourists from other countries visit here all the time, curious to learn about the deaf community,” Kanta told us, as we watched one of the village’s most impassioned dancers, 51-year-old Bengkala native Kariana, demonstrate the maneuvers with precision and grace.

Like kata kolok, kolok janger is a local invention. The dance’s choreography draws direct inspiration from the tenants of Balinese traditional dance, but adds movements and music developed specifically by the Bengkala community.

The village’s deaf troupe, comprised of up to 16 residents, accepts gigs wherever offered, but mostly dance for tourists visiting Bengkala.

While the idea of tourists gathering to marvel at disabled people dancing and observe “how they live” can be troubling, it’s equally clear locals are passionate about what they see as an opportunity to tap into Bali’s all-dominating tourism industry.

Simply put, it’s economics.

Villagers in Bengkala are mostly poor, with the majority working as hired laborers at whatever odd jobs they can find, from cutting grass to planting for farmers.

Utopia?

Active members at the Bengkala Community Center typically paint the village as a utopia of sorts for the deaf, a place where discrimination doesn’t exist and, as a Vice reporter who visited in 2015 put it, where hearing residents have to adjust to their deaf neighbors, not the other way around.

“As far as I can remember, there have been no instances of discrimination here in Bengkala … for deaf people,” community leader Ketut Kanta told Coconuts over teh hangat (tea) mixed heavily with sugar.

“We have no experience of being discriminated against,” Kariana, the dancer, agreed.

“I feel the same with normal, hearing people,” he signed to us.

“Sometimes I feel uncomfortable when I meet hearing people who can’t understand sign language. So, I just avoid them,” 77-year-old Bengkala native Sandi admitted.

The only time he feels discriminated against, he says, is when he is looking for work, something he chalks up to his age, not his deafness.

“In the past, I was physically strong enough to find any kind of job, but now that I’ve gotten older, there is a lack of people willing to work with me. I’m not physically fit,” Sandi explained, his mouth making clicking sounds as he signed to us via Ketut Kanta.

It’s hard to say whether the residents of Bengkala Village don’t want to discuss discrimination because it would undermine an idyllic image the tourist trade depends on, or if they’ve truly never experienced discrimination.

What’s clear, however, is that the educational opportunities that now draw the deaf from all over the island, were not always present.

Before the school in Bengkala became inclusive and hired teachers who could sign, an older generation — people like Kariana and Sandi — weren’t able to go to school and open their horizons to jobs beyond manual labor.

Ibu Pindu, a grandmother and deaf resident of Bengkala, who lives in a tightly packed alley with her large, extended family, is a prime example of a deaf local struggling to support her relatives.

Pindu didn’t go to school. She’s illiterate, and because she can’t hear how it’s said aloud, only knows the sign version of her name. Her entire family is deaf: her mother, husband, children, and grandchild.

“There’s something wrong with my legs, so I weave and I also make snacks to sell,” Pindu told us through Kanta.

“I don’t see being deaf as a curse, or a negative thing. I’m grateful that I was born and get to live in this world.

“But if I could have been born hearing, I would.”

The world beyond

Gede Ade Putra Wirawan, 26, a Balinese university student born deaf in Bali’s capital, Denpasar, has visited Bengkala, but has no illusions when it comes to the existence of discrimination for the broader deaf community in Indonesia

“I have experienced being discriminated against when I could not enter university,” he told Coconuts Bali in an email.

Wirawan is founder and president of the Bali Deaf Community, an organization with about 50 members, bringing together the island’s deaf for spreading awareness of deaf cultural identity to the hearing community, like teaching sign language to hearing people.

One of his primary goals is expanding education access for deaf people in the country, a key reason he joined the Sign Language Research Laboratory at the University of Indonesia’s Linguistics Department in recommending that BISINDO be included in the country’s Disability Law no. 8 of 2016.

Looking just at Bali, there are 10 Sekolah Luar Biasa (SLB), “Extraordinary Schools” that can accommodate deaf students, but they are largely concentrated in the island’s more developed south.

“Unfortunately, the problem is that special education for the deaf is limited, because the curriculum is lacking and there are a lot of miscommunications. And the access is also limited. Well, I am struggling, trying to [get the message out] about our importance to the general public, the government too,” Wirawan said.

Wirawan has been to Bengkala, and while he can sign in both BISINDO and SIBI, communication with Bengkala residents was problematic given their unique dialect.

“It’s hard to communicate with them using Kata Kolok. There was a student from (local school) Singaraja SLB who could translate,” he said. “The difference between Indonesian Sign Language in the Denpasar region and Kata Kolok is a bit [large].”

Still, while admitting the pragmatism of learning more broadly spoken sign languages, Wirawan was quick to say he believed Kata Kolok was equally worth preserving.

“If ‘kolok’ people use Kata Kolok, they are following their culture. Because they are protecting their culture and appreciating the Kata Kolok village,” he said. “Bengkala people can learn BISINDO or SIBI if they want, as long as it doesn’t interfere the village’s cultural preservation.”

Treading that fine line — between integration and cultural preservation, job prospects beyond Bengkala and a life catering to tourists — will be the challenge faced by young Asih and her deaf peers in the village in the years ahead.

For Asih’s mother, Zeni, who dreams her daughter will someday attend university, questions about cultural identity and Bengkala’s unique status in Bali are concepts that place a distant second to more pragmatic concerns.

“All I want is for my daughter to live and work as a normal, hearing person would,” she said.