Tom Waller was in London when he first heard that his brother Edward was missing. He’d received a call from his father, who told him to switch on the news: bombs had ripped through Kuta, Bali, and his brother might have been there.

“The first thing I did was try to call him on his mobile – it went straight to his voicemail,” Tom said.

At first, Tom assumed that Ed, as he was affectionately known, must be okay. It was a different time after all. In 2002, people didn’t carry their cell phones everywhere with them like they do these days. Tom, who hadn’t known Ed had taken a trip to Bali, simply thought he would still be alive, just caught up with something at that moment. But as he watched the terrible news unfold on TV, it slowly dawned on him that Ed might have been in the thick of it.

“I had this awful feeling that he might have been killed in the blast.”

The attacks

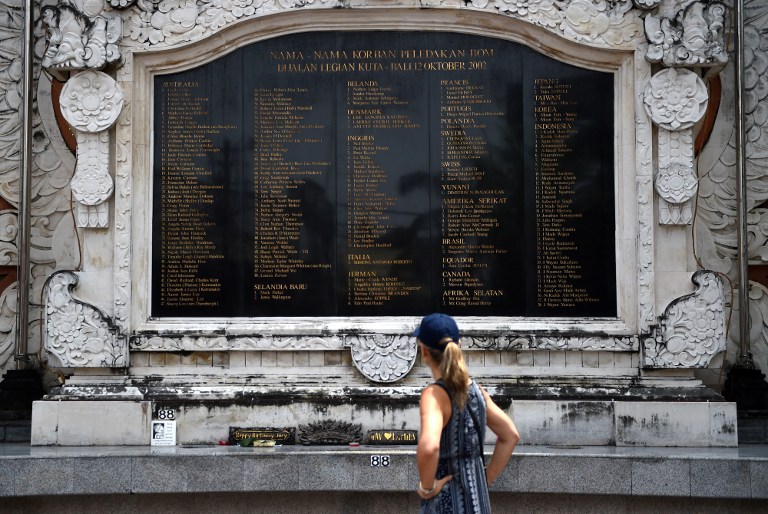

The series of attacks happened about an hour before midnight on Oct. 12, 2002, an ordinarily busy Saturday for two of Kuta’s well-frequented nightspots that are also popular among foreigners. Two bombs went off in Sari Club and Paddy’s Bar, while another exploded in front of the American consulate in Denpasar around the same time. The explosions killed 202 people and wounded hundreds more, and have since been known as the deadliest terror attack that happened on Indonesian soil.

Yet terrorist attacks, no matter how awful, always feel so far away for most individuals.

“You never think it will affect someone you know either, let alone someone close,” Tom said.

The following morning, more than 12,000 kilometers away and without confirmation that Ed was among the victims, Tom and his family waited anxiously for news. However, as he watched the reports come in all day, the horrible realization that Ed wasn’t coming back began to set in. At that point, there were no messages returned from his phone and his name wasn’t popping up on any hospital lists; it was as if Ed had just disappeared.

By the time Ed’s name started being mentioned on the list of missing people, Tom was finally hit with the realization that there was nothing he could do; his brother was gone.

“I couldn’t even remember the last thing I said to him. You just take for granted when you have a brother, that he’ll always be there,” Tom said.

“Even if he was living faraway, the idea that he didn’t exist on this planet anymore was just so unthinkable.”

Unofficial confirmation

Tom’s father managed to get in touch with the sole survivor from Ed’s group, the wife of one of the players in his rugby team. The woman was airlifted to Darwin after suffering severe burns from the blast, and she confirmed that Ed was there at Sari Club with her husband.

“She described how they were standing at the bar, pints in hand, and that they would have died instantly in the blast [as it] ripped through the nightclub and engulfed everything around her in flames,” Tom said.

“It was a miracle she survived as a witness to the terrible incident. It confirmed our worst fears that he was gone.”

For the Waller family, and perhaps hundreds others who lost a loved one in the attacks, there’s an added layer of surrealism to this loss. Tom, for one, had his DNA sample collected with a swab from inside his cheek, as authorities wanted to trace his DNA with thousands of body parts that were found at the scene in Kuta.

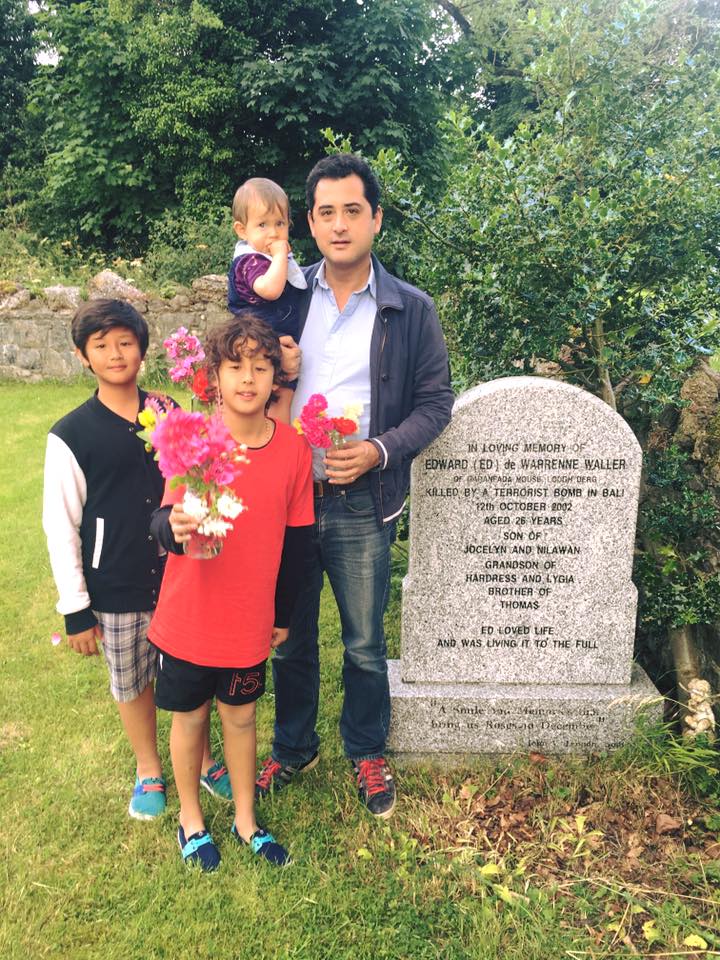

Though there wasn’t a body to bury, the family flew to their home in Ireland for a remembrance service for Ed not long after.

“Even without the body found we needed closure,” Tom said, adding that the Requiem Mass at the local parish church gave the family comfort and an opportunity to pour out their grief.

‘The right place at the wrong time’

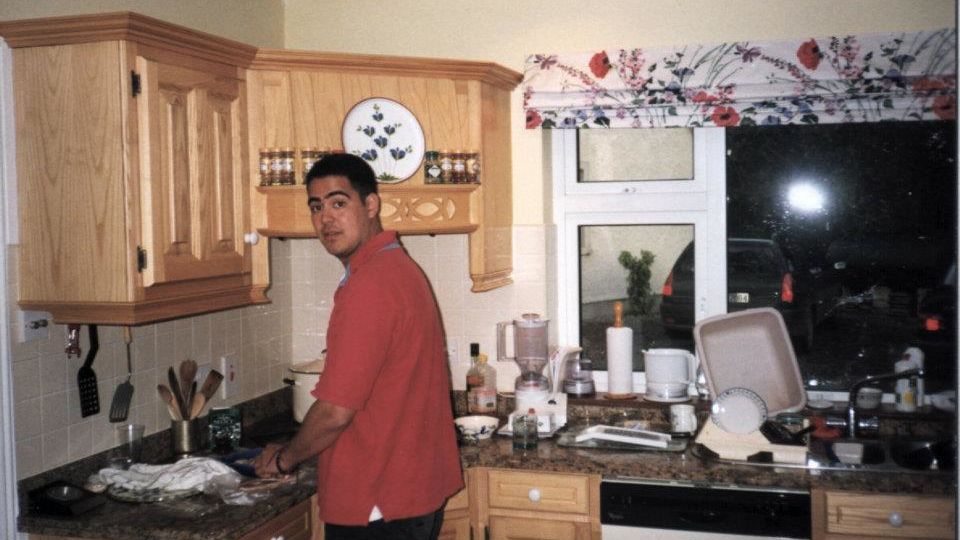

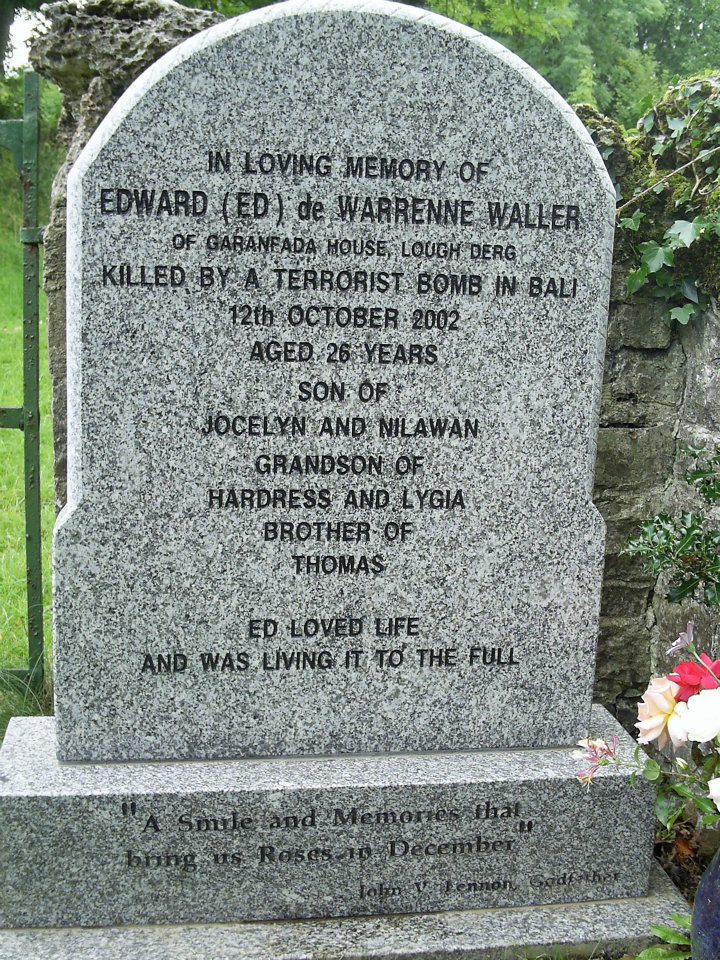

Ed died at the age of 26.

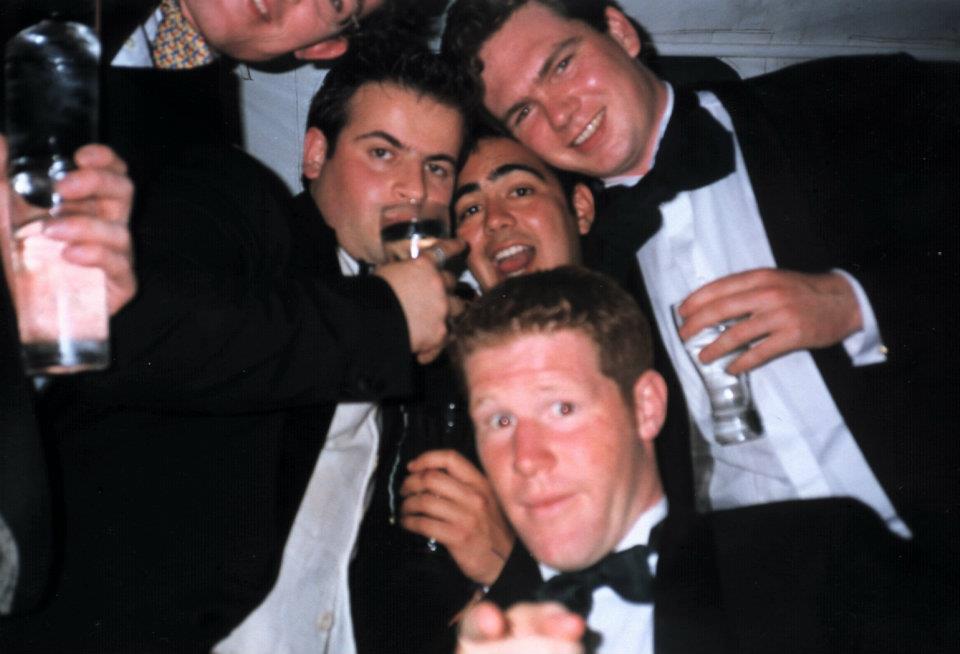

In an interview with Coconuts, Tom described his brother as “a real character.” The brothers are part-Thai, Chinese, Polish and Irish, and in Ed’s case, the mixed background and blend of cultural upbringings made him a warm and approachable guy – chatty and sociable. He was born in London and studied in Dublin, and had been living in Hong Kong for two years before his untimely passing. He had friends from all over.

“Camaraderie was important to him, and he included people wherever he went, whoever he met, even strangers would remember him,” Tom said.

Ed was a sportsman too, and he was known for playing football, cricket, hockey, rugby and even sailing. In fact, his trip to Bali was a last-minute decision because his club’s rugby team was one man short, and he decided to join them for the Bali Rugby 10’s tournament taking place that weekend. Knowing Ed, Tom knew he wouldn’t have missed that trip for the world.

Ed was one of hundreds who became victim of the 2002 Bali bombings, all of whom had hailed from different places. They came from Australia, Indonesia, the UK, Taiwan, Japan, the US, South Korea, France, the Netherlands, and many other countries.

For Tom, it brought home the realization that acts of terrorism are “unforgiving and indiscriminate toward innocent victims,” no matter where you’re from.

“The only crime Ed had committed was being at the right place at the wrong time, or even the wrong place at the right time,” he said.

There’s a lot that goes unsaid when it comes to grief, perhaps because no words can ever truly paint one’s heartbreak and loss. Tom said losing his younger brother like that has taught him how to forgive.

It also made him appreciate the people around him more. Ed’s death propelled him to start a family, a process which also helped alleviate the pain of losing someone so dear as he found joy in welcoming a new life into the world.

“Now I have four children, which I suppose is making up for the children my brother may or may not have had.”

The looming threat

Terrorism is still very much a threat in our world today, be it in Indonesia or across the globe.

Noor Huda Ismail, a former member of the hardline group Darul Islam who has since founded the Institute for International Peace Building, told Coconuts in an interview that the ability for terrorist groups to carry out a massive attack has declined drastically in recent years.

However, the rise of social media use in the last decade has democratized wayward jihad movements rapidly, which, in turn, have resulted more frequent smaller attacks

“Now you just need an app […] there’s a shift from collective action to connective action, which happens very quickly – so there are a lot of DIY-jihadists,” Noor said.

“There are many, but their skills are limited,” he added, pointing to the rise of women’s role in terrorist attacks as an example.

According to Noor, who also runs deradicalisation programmes and workshops across Indonesia, another attack at the scale of the Bali bombings are unlikely because the groups’ capabilities have been greatly crippled.

However, he said more occurrences of smaller attacks are “more concerning.” While terrorist attacks used to target only specific areas that are perceived as more popular or likely targets, these incidents now happen just about anywhere, he explained.

The perpetrators live

While grief is a very private experience for most people, Ed and other victims of terrorism from around the world died in a very public way. To talk about who we’ve lost is certainly important, but to discuss how they were victims of heinous attacks that are fueled by hate is extremely crucial, too.

Many of those who were involved in the 2002 Bali Bombings are either dead or held in maximum security prisons, yet radical ideologies persist in our world today, almost two decades after the deadly attacks.

Hambali, the military leader of Jemaah Islamiyah (JI), whose members were convicted over the bombings, was only formally accused of war crimes this year, on Aug. 31. He made his first court appearance at the Guantánamo Bay detention center that month, after being held by the US for 18 years.

Abu Bakar Bashir, a radical Muslim cleric and JI’s former spiritual leader, who is believed to have played a main role in the deadly attacks in 2002, was released from prison earlier in January after completing his 15-year prison sentence and stacking up 55 months of remission over the course of his incarceration.

Tom described the news as upsetting.

“But then justice is not always fair,” he said, emphasizing on the importance of forgiveness in the healing process.

“Although I am still angry that my brother’s life was stolen by the perpetrators, I also believe in setting the right example,” he said.

But given the chance to sit across from Bashir, Tom said he wants to ask the radical cleric to imagine himself being in his shoes.

“If I was in a room with Abu Bakar Bashir I would ask him if he were in my shoes, how would that make him feel?” Tom said.

“If he had lost a loved one unnecessarily, would he forgive those responsible for the crime, or would he seek vengeance and punishment for those wrongdoings?”