It was the middle of the day in October and Jess S was about to leave home for a lunch meeting. She’d just turned her music off when she heard a noise coming from the living room.

At first, she thought it was her father, who had just left the house. Perhaps he’d forgotten something, and was struggling to get the door open. She looked out to find a stranger peering over her lock, trying to pry it open.

Jess screamed, started running towards the stranger and was fast enough to grab the man, who appeared shocked that someone was home. She was shaking as she grabbed him, and as he sensed her fear he slipped from her grasp and managed to escape by jumping over the spiked gate, knocking it over in the process.

“We are very lucky he didn’t steal anything,” Jess, a 26-year-old German-Indonesian who has lived in Bali for the past four years, told Coconuts in an interview. “[But] it’s not the first time it happened.”

Earlier in May, Jess said someone also trespassed in her home in Bumbak, North Kuta and tried to get through the front door. The man, who was wearing a mask, said he was there to install a box. But nobody in her household called to have anything installed that day, and the man didn’t appear to have any tools with him. Jess firmly insisted he should leave, and eventually escorted him out.

“There’s a strong perception that the Balinese people don’t commit crimes because they are afraid of karma phala.”

A waning sense of safety is creeping among some of Bali’s residents, and incidents such as midday break-ins and robberies are occurring with alarming frequency these days, if anecdotal evidence is to be believed. The island is certainly no stranger to the occasional bag-snatching and mugging, but with the COVID-19 pandemic forcing people out of jobs and slumping the economy, have desperate times led to more people resorting to petty crimes?

For Claire, who requested that her last name be omitted, such an incident happened one November day at around 9am, not long after she left her villa in Pererenan, Badung regency. She said the culprit kicked her front door in and forced the bedroom doors open. Luckily, both she and her flatmate kept everything in safes, which are also bolted to the floor.

“Otherwise it would be a different story. But it was terrifying to come back to and we don’t feel as safe any longer at home,” Claire said.

With nothing stolen and no CCTV footage, Claire didn’t go to the police.

“A lot of people [told us] it’s not worth the hassle and time as there is not a lot the police can do without evidence,” Claire said.

Jess, too, only went so far as to notify the local pecalang (Balinese security officers) and her banjar (community group), admitting that she harbors a little bit of distrust with local law enforcement.

“We don’t feel like we want to really report this to the police because nothing has ever been done, we have been here for so long. Like every time we ask the police for any help nothing has happened,” Jess said.

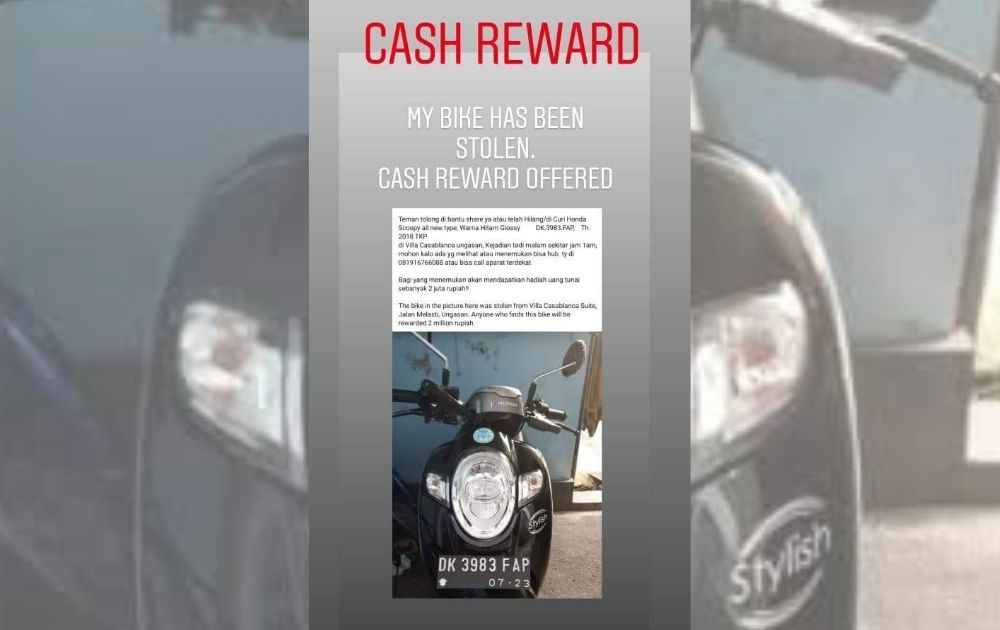

In Bali, people have taken to social media to share stories about these kinds of incidents, warning others to be careful and cautious. Pre-pandemic, those who frequent community pages online may come across only one or two of these types of posts, but they are popping up almost daily during the pandemic.

Roby Septiadi, the chief of Badung Police, said his office has received an increasing number of complaints during the pandemic. It’s natural to assume that the rise is somehow related to the ongoing public health crisis, which has severely impacted the economy in Bali, but police have yet to establish a connection.

“We cannot ascertain this just yet, because some of the suspects that we’ve arrested, not all of them are from Bali,” Roby said.

In response to the increasing number of cases, authorities say they are stepping up regular patrols and working hard to crack cases.

More hassle than it’s worth

So what actually happens when you report a crime to the police in Bali? In Pricyllia Stefanny’s case, the process took about 10 hours.

Pricyll, as she’s affectionately called, used to run a motorbike rental service. In June, she rented out a motorbike to an American national, who then allegedly gave her excuses as he failed to return the vehicle. She chased him in Kuta one day and an argument broke out between them in the middle of the road, during which, at one point, the foreigner allegedly punched her.

The 30-year-old, who came from Jakarta but has lived in Bali for seven years, described dealing with the police as “a nightmare.” She had to repeat her story over and over again to multiple officers, one of whom she said was typing up the report in slow motion.

“Unless you know a policeman with a higher rank, it’s a bit complicated and they are slow to respond or follow-up [with] the case,” Pricyll said, explaining that she happened to know someone in such a position that helped her case move along quicker.

Police managed to arrest the American tourist about a week later after he was caught stealing jewelry in Kuta. He was stopped by an angry crowd and avoided mob justice when police came and apprehended him.

“I feel like if the guy did not commit another crime, he would still be chilling at his hotel as the police officers were not fast enough to catch this guy,” Pricyll said, adding that she has since closed her motorbike rental business due to the “traumatic” experience.

AM, a 42-year-old Irish woman who requested to be identified only by her initials, went to the police after a motorbike she rented was stolen in Ungasan, South Kuta back in May. She described the process as “slow and tedious,” but overall said that the police were fine, safe for one strange request.

“And soon there was a mic in front of me and some karaoke music to sing along to. I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry but thought; heck I better get along with these guys as they may go out to at least try to find my bike,” she said, explaining that the cops assumed that she was a great singer on account of her nationality.

AM was at least thankful that her vocal prowess spared her from having to fork out some “processing fee” to file her report, which she understood was common from the stories she heard. However, more than half a year later, she still hasn’t heard back from the police about the case.

“I did call the station to follow up, but didn’t get anywhere. [I] was passed about on the phone,” she said.

Meanwhile Darren, a 67-year-old retired American, who is using a pseudonym out of concern for his safety, said police treated his case “like a joke.”

“At the beginning, the police told me not to do anything and keep quiet so they can watch and investigate. But now, almost a year has passed, so I will talk more openly,” Darren said.

Earlier this year in March, his villa in Ubud, Gianyar regency was ransacked and a thief took a number of his belongings, including a laptop and a speaker, which caused him an estimated loss of IDR14 million (US$993). According to Darren, the thieves also stole from a number of neighboring villas on the same occasion.

Some people choose not to bother with the police at all, such as with Siti Muawanah, whose motorbike helmet was stolen on two separate occasions in October, once near her home in Bumbak and another time during a visit to Pantai Berawa.

“I don’t think they would care, because what’s stolen was ‘just a helmet,’” Siti said.

And this distrust in the police to do their jobs properly may just be the thing that breeds lawlessness on the island — at least where petty crimes are concerned.

“We will always ask that the victim come to us to file a report. But if they don’t want to… there’s not much we can do,” Roby said.

Bali’s ‘holiday mood’

When you think of Bali, you don’t immediately think about the crimes happening here. The first thing that comes to mind is an image of paradise, a holiday island meant to rejuvenate the visitor, or a spiritual place that’s supposed to help you reconnect with your roots. But Bali is much more than meets the Instagram-filtered eye, and just like any other place in the world, it is not crime-free by any means.

Agung Suryawan Wiranatha, director of the Center of Excellence in Tourism at Udayana University, said visitors to any destination must always be well-informed about crime in their destination. Tourists visiting Bali, he said, are generally more relaxed about this.

“[Tourists in Bali] must be extra careful about the possibility of crimes that may arise if they are not vigilant,” Agung said.

I Made Sarjana, who is a researcher at the same center, also pointed to the lack of warnings on the island.

“In Bali, there’s rarely a warning to be cautious of pickpockets or thieves. It’s different compared to other regions [in Indonesia]. In the future, authorities must step up their role to fix this,” Made said.

Even as one reads and hears about petty crimes in Bali over the years, most would never imagine that it could happen to them. This seems to be a recurring realization among the people Coconuts interviewed for this story, who are now more concerned about their personal safety.

Darren, for example, still lives at the same villa but is due to move soon, noting that the new location has a well-organized regular patrol of banjar and pecalangs. He said he has learned that checking the background of the local banjar became an important factor in his decision on where to resettle. Like other victims, Darren is now a believer in surveillance cameras and having at least one dog for security.

“Don’t depend on the police. Just strengthen one’s own security and habits around the area,” Darren said.

Siti, meanwhile, simply resorted to buying a cheaper helmet for now, so as not to attract unwanted attention.

It’s not hard to miss that many of these incidents reportedly occurred in tourist and expat hotspots in Badung regency. There may also be many unreported cases out there, owing to the aforementioned distrust toward the police, as well as people holding back due to immigration-related reasons.

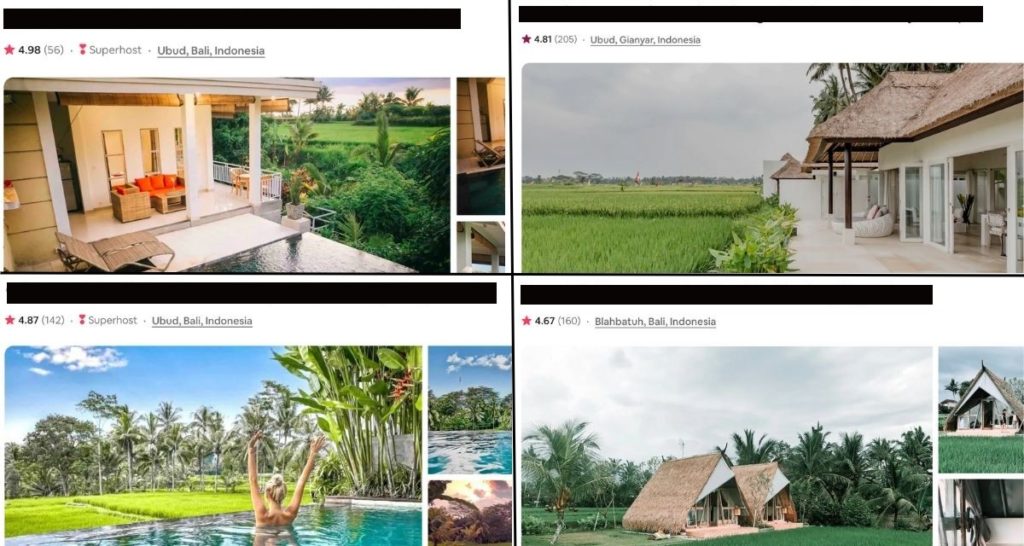

Agung said several factors contributed to the higher crime rate in popular areas, such as the tendency for tourists to be less alert and the popularity of accommodations with “open living” designs.

“Those places are popular [among tourists] but they are often away from local communities, with roads in the middle of the paddy field and entrances through small alleys, foreigners love these things,” Agung told Coconuts.

Promising unobstructed views of the paddy fields, villas with open living concepts are relatively popular for those looking to get the most out of their Bali trip. But the same design, which lacks protective walls, makes for easier access for criminals.

“Many tourists feel that Bali is safe, so they sleep without locking their doors and would open their windows. This is common among tourists who feel comfortable and safe, but I would remind them to always lock their doors and close their windows,” Agung said.

Some people appear stuck with the idea that Bali is a safe haven, but stories of leaving your motorbikes unlocked for days and no one bothering it are from 30 years ago, Agung said. These days, a combination of economic challenges and hedonism perpetuated by social media appear to have led to higher crime rates across the world, he suggested.

Made, on the other hand, agreed that keeping a pristine, crime-free image of Bali as a world-class tourism destination might be one of the reasons for the lack of exposure of petty crimes around the island.

“That might be a reason, besides the strong perception that the Balinese people don’t commit crimes because they are afraid of karma phala,” Made added, using the term in Hinduism that refers to divine retributions for one’s actions.

Jess also touched on her own experience in an open living situation at home and acknowledged that it’s a safety issue. She said having higher-walls and even installing barbed wire on top of it are essential for security. More drastically, she said that she once slept with a sickle under her bed when her father was away.

“When I do leave the house, I’m super on edge,” she said. “I’ve always been concerned for my safety in Bali, I’ve never felt safe here.”