(Warning: This article contains graphic descriptions of brutal acts of domestic violence, reader discretion is advised.)

Ni Putu Kariani’s first steps in more than a year were tentative. clumsy, painful.

She still wasn’t used to putting weight on what remained of her left leg and the area where the skin had been sewn over her lower tibia and fibula remained intensely sensitive to pressure.

The 34-year-old hadn’t walked since Sept. 5, 2017, the day her then-husband took a machete to her legs, violently hacking at her lower extremities until her legs were barely attached to her body.

A series of painful, complicated operations were endured in the months that followed, including a below-the-knee amputation of her left leg and the insertion of two titanium surgical pins in her right.

Just as painful were the endless nights where she would lie awake, reliving the attack, doubting she’d ever walk again. In her darkest hour, thoughts of ending her own life would flit through her mind. Concentrating on her two children would pull her back from the edge. They needed her.

Now, clutching the parallel bars in a small rehab room in Denpasar, each ginger step was both agony and a triumph. Looking into the room’s massive mirror, Kariani could see tears rolling down the face staring back at her.

She noticed something else too – she was smiling.

A Night of Horror, a History of Violence

Domestic violence cases in Indonesia routinely go unreported, but the exceptionally brutal nature of the attack on Kariani set it apart, with news of the gruesome crime quickly making local news outlets and sweeping across Indonesian social media.

It wasn’t the first time her soon-to-be ex-husband, Kadek Adi Waisaka Putra, had been violent toward her. It wasn’t even the first time he’d threatened her with a machete, Kariani told us softly, when we sat down with her a few weeks ago in her family home in Alasangker, a quiet village in Bali’s Singaraja area.

“Another time, before the incident, he threatened to cut off my hand with a machete, waving it at me, but he didn’t actually attack me with it. That’s why I thought he wasn’t actually serious, that he wouldn’t really do it,” she said.

Kariani had been at home watching TV on their bed that night with the couple’s son, Yoga, in their rented room in Bali’s Canggu area, where the family had moved in search of work.

On Sept. 5, 2017, Putra, a freelance tour guide, drunkenly stumbled into the tiny apartment and accused Kariani of cheating.

Nothing about that was particularly surprising. Kariani told us her husband would often return home inebriated and was frequently abusive, even before they were married.

“He once burned my skin with a cigarette butt over and over,” she said.

The familiarity of the situation meant there was no time to anticipate or react as he drew the machete and began to hack at her in a blind rage.

Kariani tried to get up and run, but her mangled legs gave way beneath her, leaving a trail of blood as her husband continued to slash her.

And then, almost as quickly as it had begun, it was over. As if a switch had suddenly flipped, her husband was suddenly apologizing, then scooping her up and rushing her to a local clinic, Kariani told Coconuts Bali.

No one else would likely have helped her that night, Kariani believes. Everyone in the boarding house was too scared of her husband , too frightened by her screams.

Putra was ultimately convicted of committing acts of domestic violence by Denpasar District Court, which sentenced him to just eight years behind bars in February 2018.

While pleading guilty and expressing remorse — as was the case here — often equates to more lenient sentencing for first-time offenders in Indonesian courtrooms, prosecutors had only suggested a nine-year sentence to begin with.

With potential sentence reductions — common around certain Indonesian holidays — and parole still a possibility, he’ll likely be out sooner still.

Almost unbelievably, Putra’s courtroom defense consisted largely of maintaining that his wife had, in fact, been cheating on him, a line of reasoning that saw Kariani, her legs still handicapped, forced to defend her fidelity to the courtroom.

Adding insult to injury, even obtaining a divorce from the man who attacked her was problematic.

“He refused to divorce me and wouldn’t provide our marriage license, which was required for the process,” Kariani said, adding that she was forced to pursue a divorce on her own, a process that is still in progress, but is expected to be completed in the next month.

To top it all off, in addition to the legal separation, she also needed a “second divorce” to be issued by her very traditional Balinese village. She was granted this by the village late last year.

“He hasn’t moved on,” she said, still clearly frightened.

“He still calls me from prison. He hasn’t given up. I just don’t answer.”

Limited Mobility

On a small island like Bali, it was more or less inevitable that Kariani and Tanty Iswana, a 36-year-old prosthetics and orthotics specialist, would eventually meet.

It happened for the first time in September 2018, one year after the attack.

It takes roughly six months for patients to recover after surgery before being fitted with an artificial limb, Tanty explained to us at the offices of her Denpasar-based NGO, Puspadi Bali.

“We need to make sure the residual limb is strong enough,” she said.

Nearly 20 years after its 1999 founding, Puspadi Bali is still the only lab in Bali offering prosthetic legs free-of-charge to those in need. Kariani’s “new legs” would end up costing the organization about IDR5 million (US$351) for her prosthetic and about IDR1.5 (US$105) million for her orthotic, a fraction of what they would cost to create in the US or Europe.

The NGO had been following Kariani’s case from afar ever since the incident, finally establishing contact in late January in the person of Pak Darma, a field worker and above-knee amputee himself from the Puspadi outreach team who was sent to her village.

What he found was a woman who, after the agonizing amputation and three follow-up surgeries, was living an almost entirely stationary existence.

While occasionally venturing out using a wheelchair, most of Kariani’s days were spent on the sofa in her parents’ living room. The only movement during the day trips to the restroom, a fraught experience.

“To go to the toilet, my father would have to lift me up and carry me,” she said.

Living in a traditional Balinese-style compound, where the house is structured around an open courtyard and the bathroom is in a separate building, means crossing an unevenly surfaced dirt courtyard, something especially daunting when rain made the surface slick.

“I was so depressed, but I had to be strong in front of my family. I wouldn’t let them see me cry,” Kariani said.

“For the first six months, I would just lie on the sofa from 7am to 9pm. Then every morning, I would cry at 4am. That would be the only time no one would see me.”

As distant as it seemed, however, a new life was closer than she realized.

Back on Her Feet

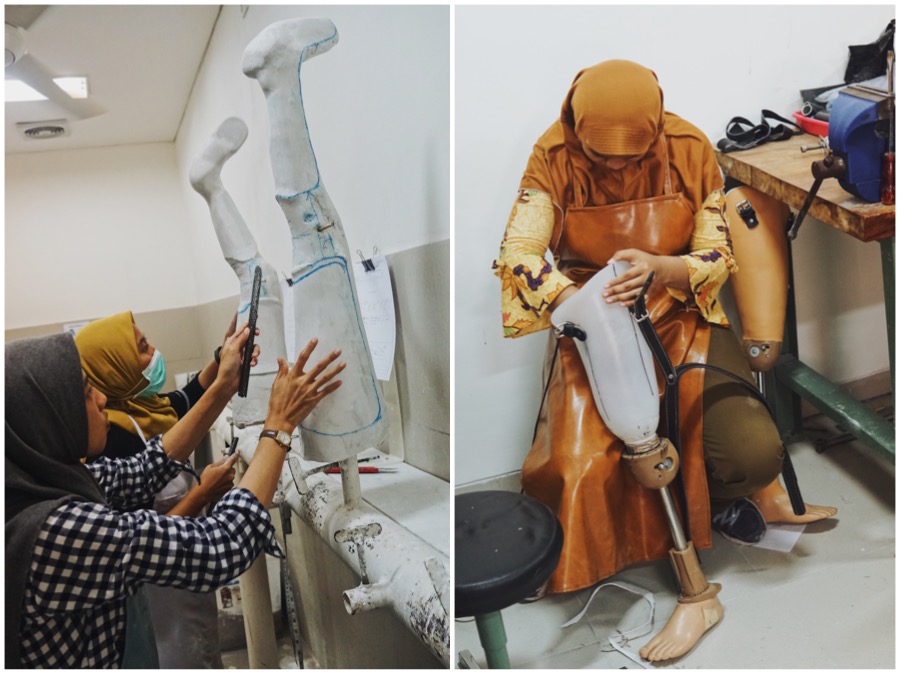

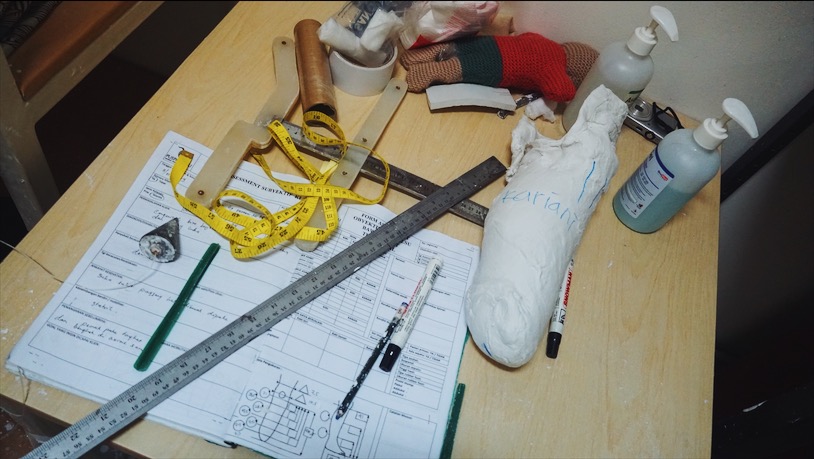

While the circumstances of Kariani’s injury were unique, the process for creating her new legs was not: consultation, construction, fitting, and finally, rehabilitation. It’s a process that Tanty has been through hundreds of times.

“When I first met Kariani… I found she not only needed a prosthetic (for her left leg), but also orthosis (for the right). Even though her right leg looks normal, inside it’s very fragile. There’s metal inside… connecting bones to make them strong again, but the muscle was still weak,” Tanty said.

Puspadi Bali builds prosthetics on-site in their own lab. The one that would be built for Kariani, what’s known as an ICRC limb, has a cosmetic cover with synthetic leather so it more closely resembles a “normal” human leg, rather than a metal rod.

Puspadi imports most of the metal ICRC components from Cambodia. Sockets are produced with local material in Bali, the plastic comes from Surabaya, and the synthetic feet come from Jakarta. Then, they build the limb, which involves melding the pieces together in their lab at temperatures as high as 250 degrees Celsius.

One major challenge for patients outfitted with prosthetic limbs for the first time is the discomfort of bearing weight on skin and bone that’s simply not used to the load.

Kariani experienced this at her first fitting on Oct. 8.

“It was a little bit difficult for her to be able to stand, because when wearing a prosthetic for the first time, she was putting a lot of pressure on a specific area, like on the front part of her knee,” Tanti recalled.

“She was still trying to adapt to that, but I could see it on her face, she looked very happy because she could get up from her wheelchair and try to stand. Even though she was using her hands and holding the parallel bar for support.

“She couldn’t stand for one hour, but for me that was a big deal, because she felt so happy standing. Even though she felt pain, she could deal with it.”

Initially, Kariani could walk just two or three steps.

“In the first week, there was a blister, so she needed to adapt to that, because the weight was on the knee area. When we stand on our feet, it’s a different type of tissue, not like the knee area. Once the skin got thicker, it was no longer as painful.”

It usually takes patients with new prosthetic limbs anywhere from two weeks to a month to develop the blister to which Tanty’s referring. For Kariani specifically, the skin thickened into a callous over the course of two weeks.

That’s when she could really begin focusing on the stability and balance needed for walking, Tanty explained. By week four, she was able to walk with one hand on a crutch around the Annika Linden Centre, the Denpasar complex in which Puspadi Bali is based.

For most, getting a prosthetic limb is a journey, not a one-off experience. As the body changes during the healing process and things get worn out, updates need to be made.

Kariani came back to Puspadi on Jan. 15 to try out a new joint that allowed increased plantar — downward flexing movement of the foot — mobility on her orthotic brace.

It was during this visit that the Puspadi team noticed that Kariani would need a new prosthetic leg entirely, a smaller one, because her left leg was smaller now than it was a few months ago and no longer fit comfortably.

Volume reduction, or “shrinkage,” is common with amputees even months after their prosthetics fittings, as muscle atrophy occurs. And so, the Puspadi team repeated the entire process, coating Kariani’s stump in plaster to make a cast, which they used to model a new prosthetic they were able to turn around in just 10 days.

Even as Kariani was learning to use her prosthetic limb, she was getting used to her AFO, the brace that supports her right leg.

Viola, an interning student from Jakarta, fashioned a custom joint, designed to give Kariani increased mobility in the orthotic to recreate a plantar movement. While modeled after the industry-standard Oklahoma Ankle Joint, Kariani’s joint is experimental and has allowed her to use her right leg with greater ease.

In one to two year’s time, it’s likely Kariani will need a new prosthetic, Tanty estimated. The need for a new orthotic will likely come sooner.

Complicated Family Matters

Kariani has no desire to move back to Canggu, the site of the attack, saying she wishes to remain with her parents for the time being.

The situation with her children, however, has left her future plans cloudy at best.

While Kariani technically has legal custody, both her son, now 10, and 15-year-old daughter live down the street with her ex-husband’s family, a situation that has more to do with family politics and Balinese village tradition than the courtroom.

“The children are allowed to visit their mother daily, but they must sleep at her ex’s family’s house,” Kariani’s mother, told us, looking at her daughter with a worried glance.

“Allowed” means what’s permitted by Putra’s family, she added.

“Custody does fall into the hands of Kariani,” says Gusti Ayu Agung Yuli Marhaeningsih, 34, a lawyer from Bali Legal Aid Institute (LBH) who has been representing Kariani.

However, Kariani’s family “still respects cultural customs”, that the children stay with their “paternal lineage”, explained Agung.

“When talking about patrilineal customs in Bali, the explanation is long,” she added.

In other words, it’s complicated.

“I’m just happy I can see them and spend time with them. They are both so busy. After school, my daughter is teaching children dancing, playing guitar, and doing tae-kwon-do competitively. She won four competitions,” Kariani said, beaming with pride.

“And Yoga is a busy boy. He has a lot of activities, playing with friends and learning guitar. It’s also better for him over there [at her in-laws], because there are more children there for him to play with,” she said diplomatically.

But things are far from smoothed over between the two families in Alasangker Village.

“They haven’t apologized for him, they haven’t said sorry. They have just ignored me,” Kariani said.

More worrisome is what happens when Putra is released from prison.

“Of course I’m afraid,” Kariani responded, when we asked, prompted by the calm, reserved demeanor she displayed when discussing her children.

“It’s just my father (her only male relative)… he’s already old. I don’t feel safe,” she told us.

Finding New Purpose

While the custody situation remains, at least for the time being, out of her control, Kariani has slowly gone about building a life for herself.

A GoFundMe page launched in the wake of the attack has helped set up long-term monthly payments to support her and her children, but she’s earning extra and finding day-to-day purpose in a new enterprise: creating bags.

Working from her bedroom with a sewing machine purchased following her surgeries, Kariani resourcefully makes the bags from leftover, discarded curtain materials and batik that she sources from Jogja.

The burgeoning plastic-free movement in Bali has given her another outlet for sales: making reusable shopping bags out of the iconic Balinese saput poleng — the black and white checkered fabric you see all over the island.

And she’s doing it all with no formal training.

“I just watched a bunch of YouTube videos and learned how to sew and got ideas from there,” she said.

“I can make nine to 10 bags in one day if I’m focused. If I’m not focused, maybe four or five.”

An Australian friend of Kariani brings the bags to Australia and sells them there, while they are also circulated in South Bali, where they’re sold at shops and restaurants for just IDR50k (US$3.50).

Everyday life has become exponentially easier now that she no longer has to use a wheelchair, a crutch, or rely on her father to go to the bathroom.

She sometimes even drives a scooter.

“But only when papa’s not watching, because he worries too much if I drive.”

“Once, my leg fell off when I was on the back of my friend’s scooter,” Kariani told us, the memory sparking a convulsive chuckle.

Her infectious smile was familiar. We had seen it in a mirror, three months earlier, in a Denpasar rehabilitation facility.

These days, it’s appearing much more frequently.

If you’d like to learn more about Puspadi Bali’s work and how you can help their cause, go to their website. To support Kariani and receive updates on her status, visit her GoFundMe page.