Before we begin, let us assure you that, most (if not all) Indonesians will appreciate your effort to learn and use Bahasa Indonesia AKA the Indonesian language. Don’t believe us? Check out Australian actor Chris Hemsworth impressing Indonesian interviewers with his basic Indonesian skills.

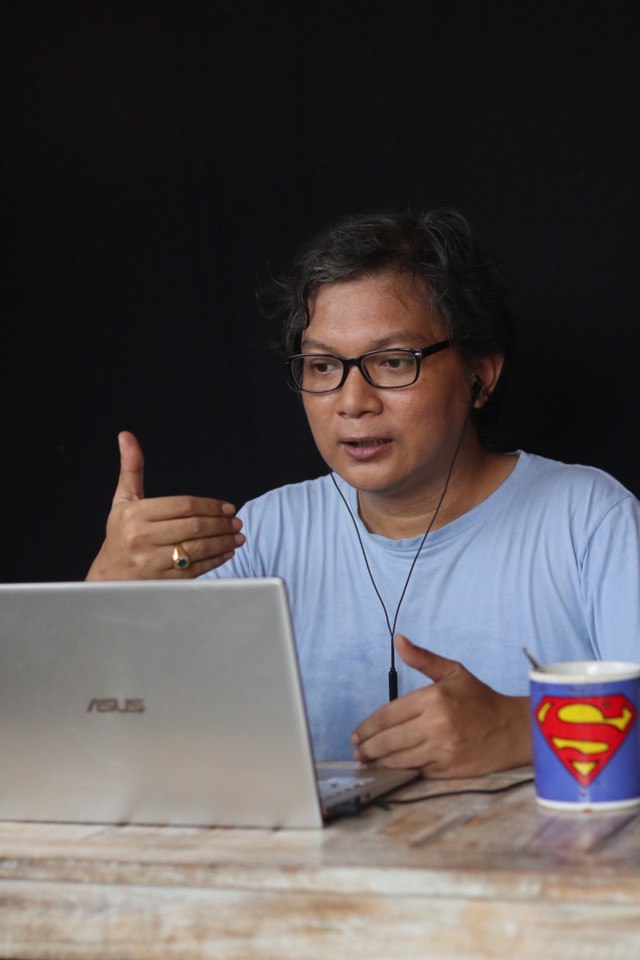

That being said, there are some phrases and words that, based on our observations at least, are commonly used by non-Indonesians that virtually no Indonesians ever say in real life. We recently spoke with Ubud-based Bahasa Indonesia teacher Daniel Prasatyo who told us about five awkward words/expressions that many foreigners use when speaking the language.

Daniel stressed, however, that people should not worry too much if they have used those expressions without realizing how out-of-place they come across.

“Indonesians are very tolerant [when it comes to foreigners learning their language],” he said.

Still, since these common mistakes are actually very easy to fix, why not do just that? Ayo!

Anda (you)

We have seen numerous foreigners who like to use anda when addressing someone in Bahasa Indonesia. While it is not inherently wrong (the word is in the dictionary, after all), Daniel said that people need to realize that the Indonesian language does not have a general use word for “you” (unlike in English).

“‘You’ in Indonesian will be determined by the relationship between the two speakers,” Daniel told Coconuts Bali.

“Anda is mainly used to indicate that there is no personal relationship between the two speakers and there will be no personal relationship between the two speakers. It is cold and distant.”

Daniel explained Indonesians would immediately refer to the person they are talking to as if they are talking to a member of the family. For example, if said person is older than them but could still be considered their sibling, they might use the gender-neutral Kak, or Mas and Bang (for older brother) or Mbak (for older sister).

You can also use the Balinese versions of these terms, which are Bli (older brother) or Gek (older sister).

If said person is old enough to be your parent, or if you want to show them respect in the way you would an elder (such as your employer), you would use Bapak (Sir) or Ibu (Ma’am or Madam) or “Pak X” or “Bu Y”.

“So let’s say you want to say ‘Do you want coffee?’, instead of saying, “Anda mau kopi?”, say, “Bapak mau kopi?” or “Pak Made mau kopi?” Daniel said.

If the person you are referring to is of a similar age to you, you can either address them by their name (“Made mau kopi?”) or just skip the “you” entirely and simply ask, “Mau kopi?”

Easy fix, eh?

Senang bertemu dengan Anda (nice to meet you)

Ah, yes. The classic “nice to meet you.” While senang bertemu dengan Anda is, indeed, a direct translation of this standard greeting, the truth is no Indonesians use this in real life.

“If you’ve been using this expression, do not worry much,” Daniel reassured.

“It is harmless. Indonesians who are familiar with English would understand, and those who are not familiar with English wouldn’t be offended.”

Furthermore, Daniel explained that Indonesians heavily rely on context when it comes to conversations, and thus would know whether “the meeting” is actually nice or not.

“Indonesians will keep on asking questions, trying to keep the conversation going when they are happy meeting you. If not, we would not ask questions, reply in short answers, or even excuse ourselves,” he said.

In other words, you can just immediately skip to the small talk for pleasantries when meeting somebody for the first time, instead having to say a direct translation for “nice to meet you.”

ALSO READ:

Apa kabar? (What’s the news?)

“Apa kabar?” is a very common expression that most learn at Indonesia 101 that is taught to be the equivalent of “how are you?”. However, as Daniel noted, “apa kabar?” literally means “what’s the news?” and Indonesians will only use it in real conversation when they have not seen the person for quite a long time.

“We cannot expect every expression, especially in social settings, to be easily available in another language or another culture,” Daniel said.

“When you meet someone regularly, say daily, that person will find it hard to answer as nothing much has changed or could have changed since the last time you saw them. No newsworthy events, such as marriage, birth, death, moving, could have happened in the meantime. Or, if they did happen, you should’ve known,” said Daniel.

“I would suggest that ‘Apa kabar?’ can work well if the last time you met or talked to them was about a week ago or so,” said Daniel.

He then suggested that the best way to acknowledge someone’s presence is by asking the next question that arises in your mind. Questions such as “Rambutnya baru? (New hairdo?)” if said person looks like they might have had a haircut, or “Dari mana? (Where were you coming from?)” if you notice that they did not come from the usual direction.

If you genuinely want to ask something like “how are things?” to an Indonesian, you can ask them “Sehat?” (meaning “Healthy?” or “is your health okay?”) as a workaround.

Saya pikir (I think)

Daniel said that one of the most important things that your teacher might forget to tell you is that the first word of every sentence is the main topic of the conversation.

“Most of the time, when the context is clear, Indonesians just drop ‘I’ and ‘you’,” he said.

So for example, if you want to tell someone about your favorite book, you might say “I think this book is good” in English. The direct Indonesian translation, “Saya pikir, buku ini bagus” has a whole other meaning.

“What comes across in this sentence here is that we are talking about you, not the book. Not only that, though. It also comes across as ‘Let me do the thinking as I’m the only one who can think,’” he said.

“It is totally harmless in English, but in Indonesian, it really feels condescending.”

The workaround? Daniel suggests the following phrases as examples of what you can say instead.

- Buku ini bagus. (This book is good.)

- Sepertinya, buku ini bagus. (It seems like this book is good.)

- Rasanya, buku ini bagus. (It feels like this book is good.)

- Menurut saya, buku ini bagus. (In my opinion, this book is good.)

Saya cinta kamu (I love you)

Yes, yes, if you look in the dictionary, cinta is indeed love in Indonesian. Still, the phrase “I love you” in Indonesian is actually not conveyed by its direct translation “Saya cinta kamu.”

Daniel explained that “love” in English covers many kinds of love.

“You can love your country, your language, your mother, your partner, and your children,” he explained, adding that “cinta” is different.

“In literary works, cinta is often used as love, indeed. But the Indonesian language in literary works is of the exaggerated variety. In real life, we mainly use cinta for our country, land, and language, in a patriotic way,” he explained.

“To another person, we prefer to use ‘sayang’, which means ‘care a lot about, regard as precious’,” Daniel said.

The second thing, according to Daniel, is the use of saya (I) and kamu (you) in this context.

“This is the one that can come across as problematic. We use the saya-kamu pair to indicate that ‘saya’ is in a higher position than ‘kamu’. We usually use this pair of pronouns in employer-employee situations, or between an adult and a child. This is why it sounds wrong,” he said.

“When you are already at the level of having a personal relationship and have shared some secrets, the best pair to use is ‘aku’ (I) and ‘kamu’.”

In conclusion, Daniel said, the most appropriate Indonesian way to say I love you is “aku sayang kamu.”

Hopefully, these lessons can help you speak Indonesian like a local. Daniel promises Indonesians will appreciate you even more when you attempt to understand the underlying cultural differences reflected in the language.

That said, he also reiterated that Indonesian learners should not worry too much if they have used these phrases before.

“You don’t need to call out your teachers, or throw away your books,” Daniel said with a smile, adding that the textbooks that people are reading might have been written many years – even decades – ago.

“Most of the authors are linguists, academics, who spent most of their lives studying the language, not actually using it themselves in different settings. Your teachers also learned from those books,” Daniel explained.

Terima kasih!