Seven months after the US House of Representatives overwhelmingly adopted a resolution labeling Myanmar’s expulsion of more than 700,000 Rohingya’s a “genocide,” the US State Department has moved to act against four of the country’s top military commanders.

Commander-in-Chief Min Aung Hlaing, Deputy Commander-in-Chief Soe Win, Brigadier General Than Oo, and Brigadier General Aung Aung have been sanctioned for “gross human rights violations, including in extrajudicial killings in northern Rakhine State, Burma, during the ethnic cleansing of Rohingya,” according to a statement released early this morning Yangon time by US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo.

It represents the first official action taken against Myanmar’s top military leadership by any country, Pompeo said.

The designation, which falls under Section 7031(c) of the FY 2019 Department of State, Foreign Operations Act and Related Programs Act. Section 7031(c), means that the four and their immediate family members are barred from entry into the United States.

The same act was recently invoked in the banning of 16 Saudi nationals for their roles in the murder of political activist and Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi.

The statement announcing today’s sanctions cites ongoing reports of human rights violations, and the fact that the Myanmar government “has taken no actions to hold accountable those responsible.” In the final paragraph, it specifically refers to Min Aung Hlaing’s decision to release soldiers involved in the Inn Dinn massacre after only a few months in prison as an example of that lack of accountability.

Two Reuters reporters would subsequently spend more than 500 days in prison for their work in uncovering the grisly details of the massacre.

US officials voiced hope that the sanctions would help the civilian leaders exert control over the army, which the State Department said was alone responsible for the anti-Rohingya campaign.

“Our hope is that these actions will strengthen the hand of the civilian government [and] will help to further delegitimize the current military leadership,” an official said on condition of anonymity.

Erin Murphy, a former State Department official closely involved in the thaw in US ties with Myanmar, said the ban would affect not so much the generals directly, but their children or grandchildren who want to come to the United States as tourists or students.

While saying the travel ban provided a tool to encourage change, she doubted it would change attitudes toward the Rohingya, who are “almost a universally despised population.”

“You’re talking about changing deeply held xenophobic and racist attitudes and a travel ban alone isn’t going to change that,” said Murphy, founder and principal of the Inle Advisory Group, which specializes in Myanmar.

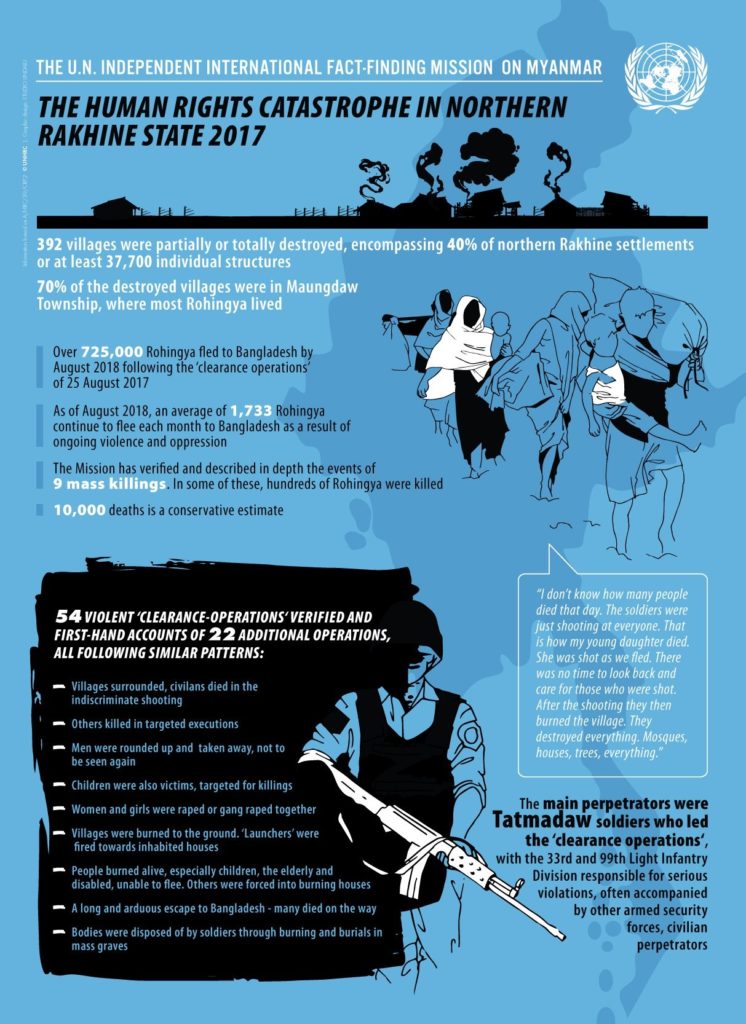

Months before the US Congress passed its resolution, a UN fact-finding mission had released a damning report documenting military atrocities committed in not only Rakhine, but in Shan and Kachin states as well.

That report, compiled over the course of 18 months, included interviews with more than 850 victims of military violence, many of whom described torture, gang rape, enslavement, and wholesale slaughter.

Members of the UN mission used the term “genocidal” to describe what they found, and recommended that Myanmar military leaders face prosecution at the International Criminal Court at the Hague.

Additional reporting by AFP.