A story published by The Irrawaddy spent less than a day online yesterday when it was discovered that what the story’s authors presented as current news actually took place over a year ago.

In the Myanmar-language story, titled “Weapons plundered from Bangladeshi refugee camp guards,” The Irrawaddy reformulated a report by AFP and published by the Daily Mail about armed attackers raiding a security post at a Rohingya refugee camp in southern Bangladesh.

The attackers killed one Bangladeshi guard before they made off with 11 rifles and 570 rounds of ammunition. Police told AFP that Rohingya refugees themselves were being considered as suspects in the attack.

“The miscreants could be hiding inside the camp,” a police inspector said.

The report fits neatly into the Myanmar government’s narrative about the refugee crisis. It raises suspicions about Rohingya refugees and their alleged links to militant groups, whose activities the Myanmar government uses to justify its continued displacement of the Rohingya from their homes.

Rarely is this narrative challenged by Myanmar-based news publications, but in this case, serious doubts were raised for one simple reason – the report was false. The attack was not carried out on October 13, 2017, as The Irrawaddy claimed, but on May 13, 2016.

The inaccuracy was caught by Rohingya activist Nay San Lwin, who called attention to it on Twitter. The story was removed from The Irrawaddy’s website less than an hour later.

Fake and fabricated news posted by @IrrawaddyNews was caught by me. @MailOnline posted a news on May 13, 2016. Here’s the link – https://t.co/iKIv8JAxl7 – The incident happened on May 13, 2016. Today Irrawaddy Burmese posted the translation of Daily Mail’s news — read thread — pic.twitter.com/dF7GZzUt6o

— Ro Nay San Lwin (@nslwin) October 16, 2017

When asked about the story, The Irrawaddy’s Myanmar-language editor Ye Ni said: “It was a mistake. The regional desk translated it as they thought it was in October 2017. When we realized that was an old story, we took it down.”

Whether it was an honest mistake or not, the false report fueled anti-Rohingya sentiments among The Irrawaddy’s readers. Before it was deleted, one Mandalay-based Facebook page with over a million followers shared the story, inviting commenters to warn of the rising threat of “Bengali terrorists.” Even Myanmar’s Ministry of Information shared the story as if it had just happened.

It was also shared by former information minister Ye Htut, who has thousands of followers on Facebook and now works as a visiting senior fellow at Institute of Southeast Asian Studies in Singapore. (He eventually deleted the article from his timeline.)

The confluence in the messaging of The Irrawaddy and the military-affiliated former information minister would be surprising to those who recall that The Irrawaddy has its roots in Myanmar’s pro-democracy struggle and was once considered the most professional and trusted news source in the country.

However, in the weeks since the Myanmar army’s mass displacement of Rohingya Muslims from the country began, the independent outlet has quickly adopted the government’s script.

The Irrawaddy has traditionally referred to Rohingya as “Rohingya” on its the English-language site and as “Bengali” – a term that implies they are illegal immigrants from Bangladesh – in Burmese. A few days after the ARSA attacks on August 25, the English-language site began referring to them only as “self-identifying Rohingya.”

Several of the publication’s employees have resigned since the policy was introduced.

Nay San Lwin, the Rohingya activist, said he has written to The Irrawaddy’s chief editor Aung Zaw to correct this inconsistency.

“He never responded to me and keeps using ‘Bengali’ in the Burmese version and ‘Rohingya’ in English to please their funders…Some of the news they post in Burmese is complete propaganda,” he said.

In September, editor Aung Zaw told CNN that “Rohingya is not an ethnic minority that belongs to Burma.”

Yesterday’s fabrication, Nay San Lwin said, was “the worst in The Irrawaddy’s history,” but it was also the culmination of a process that has been changing the entire media landscape in Myanmar since 2012, when communal violence between Rohingya Muslims and Rakhine Buddhists ignited a Buddhist-nationalist fervor that has become a major force in the country’s politics.

He said: “All the [local media outlets] have changed since 2012. BBC Burmese, VOA, and RFA are biased. They have tried many times to use the term ‘Bengali,’ but as I keep complaining to them through media directors, they use ‘Rohingya’ sometimes and mostly refer [to us] as ‘Muslims.’”

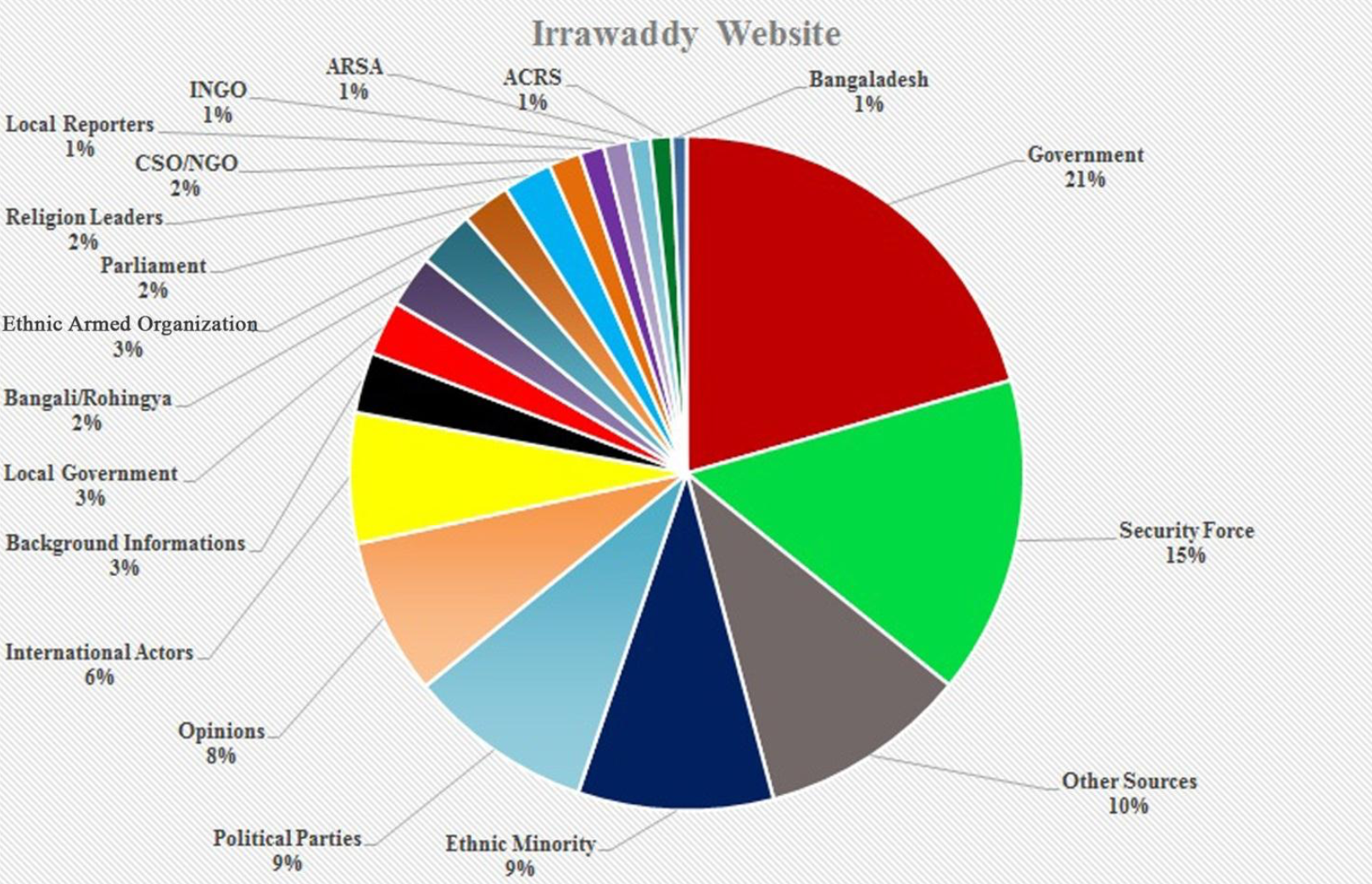

A report published by the Myanmar Institute for Democracy last week found that The Irrawaddy’s coverage of the first two weeks of the Rakhine crisis “mainly relied on the news released by the Information Committee, the Sate Counsellor Office, the President Office, and the Chief of Defense Office.”

“The problem with all Burmese media is racism,” said Nay San Lwin. “If the Rohingya were Buddhist, I’m sure they wouldn’t take the military’s side.”