Filmmaker Min Htin Ko Ko Gyi received an usual censorship request for his 2013 film Thanakha.

“There was a scene where a couple makes love in the film,” he said. “I hadn’t filmed any adult scenes but put 5 seconds of black frames right after they went to bed holding hands. But they asked me to remove the black frames.”

Their surprising answer?

“The audience will think whatever they want because of those 5 seconds of black frames,” he said they told him. “They will imagine too much.”

So like nearly every other director is forced to do, he made the cut.

“All I wanted to show the audience was the moment the young couple made love according to their desire,” he said. “I left it for the audience to enjoy and let them take it as they want. But censorship did not allow it.”

For long, a handful of people have held the power of life or death over Myanmar’s films by standing between them and release with the arbitrary power to hold certain scenes objectionable by a set of very subjective criteria.

While the official censors don’t overtly ban films – their refusal to certify them has the same result – they frequently order scenes cut for capricious reasons, a frustration nearly every director has experienced in their career. Now, the country’s filmmakers are demanding changes to that system, the laws and more in the name of evolving the artform.

They want to be able to make films that include adult themes and aren’t held to vague rules about “preserving the union,” promoting ethnic harmony, preserving traditional culture and more that have been bent to fit the personal whims of the censors.

“Whenever we think of making a film, we will have to avoid the list mentioned above, even if the script just makes everyone in this industry disappointed,” said Ar Kar, director of the well-known 2018 film The Mystery of Burma. “So the only way to fix it is to change the rating system and remove this censorship; let the artists create his/her own film freely.”

That means coming up with a standard ratings system like those used elsewhere.

And they’ve made headway. Na Gyi said the Ministry of Information has agreed to revise the rules and has asked for support within and without the industry to get it done.

On Wednesday, their petition was signed by Nyi Nyi Htun Lwin, chairman of the Myanmar Motion Picture Organisation.

Of the four films Ar Kar has made, he said all were censored in one way or another.

“I had to reshoot, re-edit and reapply for censorship again and again, and I hate it,” he said.

As the board’s decisions are issued in private, no one even knows how many films have been censored or blocked by the board, at least outside the Myanmar Motion Picture Organization.

Coconuts contacted the organization to get an answer; it declined to provide one.

Director Na Gyi, director of the award-winning film Mi, said he got behind the campaign because the film industry has lagged behind other media in free expression.

“Since there is no more censorship on books, paintings and other arts, film is the only thing that’s still controlled by an organization,” he said. “Besides, those regulations are also old-fashioned. Thus, we want to change it, once and for all.”

Famous performers including Nay Toe, Kyaw Kyaw Bo, Tun Tun, Daung, Ye Lay, Ye Tike, Pai Phyo Thu as well as serious directors Maung Myo Min (Yintwin), Na Gyi, Htoo Paing Zaw Oo and writer Chit Oo Nyo are among those supporting the reform campaign which began on the Writers and Directors Organization Of Myanmar, where many have contributed articles about censorship and the ratings system.

Myanmar filmmakers say the obsolete rules are holding the industry back from further evolving. Ar Kar said audiences have seen improvement since late 2018, when movies by young filmmakers overtook the tacky and reliably offensive films that had been a cliché for decades. For long, the censors did nothing about routine homophobia, mocking of ethnic minorities, ridiculing of people with disabilities and more tropes of Myanmar’s movies.

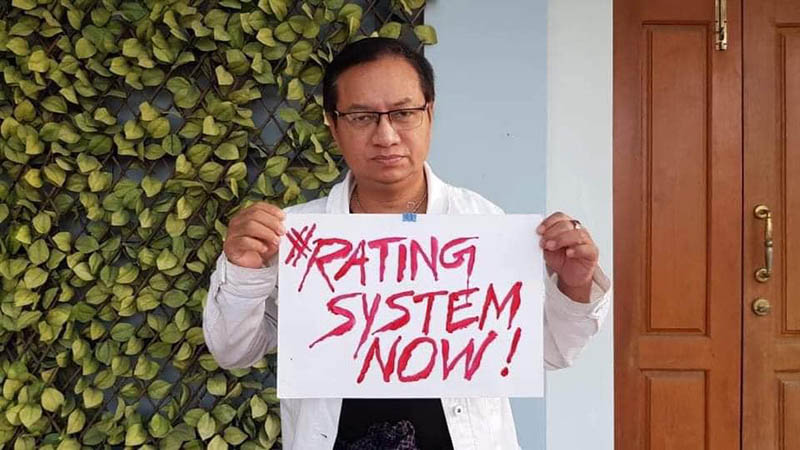

The campaign began in earnest on Dec. 11 and is first focused on changing the ratings system. Participating artists have taken part by posting photos of them holding captive cards on their Facebook pages, saying #RatingSystemNow.

“First, the ratings system. Then we will continue to push for the film bill to be implemented as soon as possible,” Ri Zaw said, referring to the longer-term goal of changing the 24-year-old Motion Pictures Law, which dictates that every film must pass two layers of censorship that begin with a script review.

Director Cho Two Zaw, also known as Aung Zaw Min, said it’s about removing authoritarian interference from the relationship between artist and audience.

“There should be no barrier between the artist and the audience,” he wrote. “This censorship is about a group of dictactorship’s dogs who insult both the artist and the audience. They will be far from the art, 10 lives away.”

Related

Myanmar government bans screening of ‘Twilight Over Burma’

New wave filmmakers turn an uncensored lens on Myanmar

Myanmar ranked among the top ten most censored countries in the world

Reader Interactions