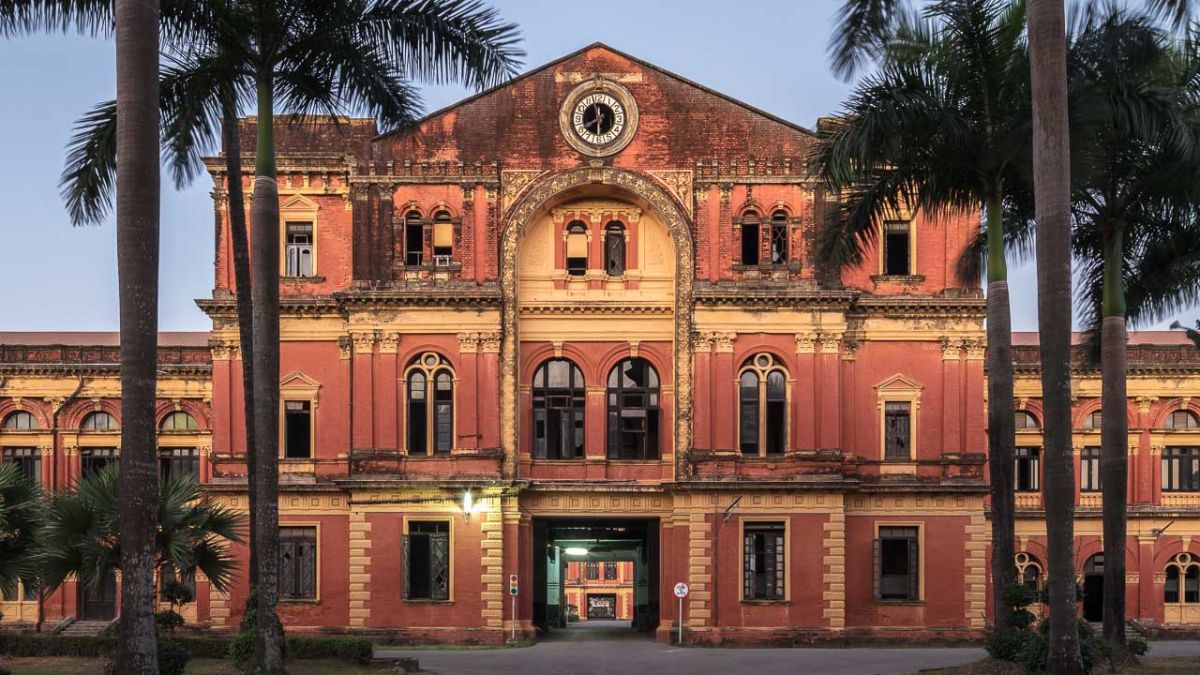

The Secretariat, where independence leader Aung San was assassinated in 1947, is one of the city’s most spectacular heritage sites. Photo / Manuel Oka

Deep into researching the upcoming Architectural Guide to Yangon, which details the history of dozens of the city’s most significant buildings, Elliott Fox had trouble tracking down an essential piece of information: the age of a historic mosque near Sule Pagoda.

“I blagged my way into the mosque and up the stairs and found this caretaker who was about 150 years old and spoke impeccable English,” Fox recalled recently, “he was sitting in this tiny office that was just overloaded with typewriters and maybe a filing cabinet in the corner.”

The elderly caretaker took a look at him, rifled through stacks of paper, and drew out an eight-page typed fact sheet about the building. He’d had it for years – but nobody had ever come, he said. “It was like something out of a film,” said Fox.

The book, which Fox wrote with economist Ben Bansal and photographer Manuel Oka, owes a large debt to people like the caretaker of that 19th century mosque.

Recent months have brought more additions to the growing body of literature about Yangon’s numerous historic buildings, most notably Yangon Echoes, Virginia Henderson and Tim Webster’s picture-led oral history of residents.

But until now there has been no encyclopedic, accessible guide to the city’s significant structures – old and new – and information was hard to come by.

This mosque, in downtown Yangon, was constructed between 1914 and 1918. Photo: Manuel Oka

“The heritage buildings were mostly well-researched,” said Fox, referring to the hundreds of colonial-era structures that still stand in the former capital.

“There were lots of secondary sources, lots of things that had been written recently, and lots of materials from the colonial archives. The bits that were harder to research were things like 50s architecture, in which nobody had really taken an interest.”

As well as the grand relics of the British occupation – the glitzy Strand Hotel, the towering banks and red-bricked government buildings – many of which were abandoned after the capital moved to Naypyitaw in 2005, the city is littered with eye-catching relics of the era under Myanmar’s first Prime Minister, U Nu.

“There was still this kind of post-independence optimism,” said Fox, singling out the curving, cantilevered Tripitaka Library on Kabara Aye Pagoda Road as one of his favorites.

The Tripitaka Library on Kabar Aye Pagoda Road was built in the 1950s, shortly after Myanmar gained its independence. Photo: Manuel Oka.

“That building in particular was an attempt to create a forward-looking post-colonial Buddhist architecture. There was no particular template for what that would look like, and that’s what the library is.”

To track down details missing from many contemporary accounts, Fox and Bansal scoured through old, seldom-read books by architects and historians. They walked around and sought help from individuals with a personal interest in the buildings.

“We were really surprised by how engaged and how active the Burmese community was,” said Fox, adding that the Facebook page for the book has 9,000 fans – mostly Myanmar citizens.

The colonial-era core of downtown Yangon, seen from Strand Road. Photo: Manuel Oka.

As much as the guide is a record of the past – it features colorful stories from the buildings’ histories– its authors are careful not to advocate the Disneyfication of the city’s past at the cost of moving Myanmar forward.

In between the building entries are chapters reflecting the impact of political and social changes on the city, including the literal whitewashing of Yangon after the violent crackdown on student protests in 1988.

“We were trying, with the book, not to fetishize the heritage period too much,” said Fox, “precisely because a lot of people who come here tend to do that and obviously all these buildings are stunning, but it’s not for us to say what the Yangon City Development Committee and Yangon residents should do with them.

“I hope a lot of it will be kept but it’s understandable that they also want to build things which are cheap and more functional and do it quickly because they need affordable housing, they need office space, they need all these things for the future.”

The city that emerges in the Architectural Guide is both living and changing. Next to entries about once-grand, now dilapidated colonial-era wooden mansions like the Pegu Club are descriptions of modern architectural additions like the Sakura Tower and even Star City in Thanlyin Township.

“The buildings that are in the book are not necessarily because they’re beautiful,” said Fox, “but because they say something about what Yangon is, or what it’s becoming, and how things might evolve.”

Architectural Guide to Yangon will be on sale at Monument Books from December.