In a country that is remarkably sensitive to dissent, Myanmar’s teens are increasingly turning to one of the most irreverent forms of social critique to make their points — memes.

Dissatisfied with the lack of ideological diversity in the country’s major institutions, an army of memelords has sprung up to wage war against stupidity and hypocrisy from behind their computer screens. Through memes, these young people are opening up to new ideas and challenging old ones.

Over the past few years, meme groups such as BUMi (Burmese Uncensored Memes-i) and GUM (Global Uncensored Memes-9) have grown massively popular among Myanmar’s young. First appearing around 2012 and gaining tens of thousands of members by 2015, Myanmar’s meme groups allow young people to popularize ideas that would be unthinkable to their parents.

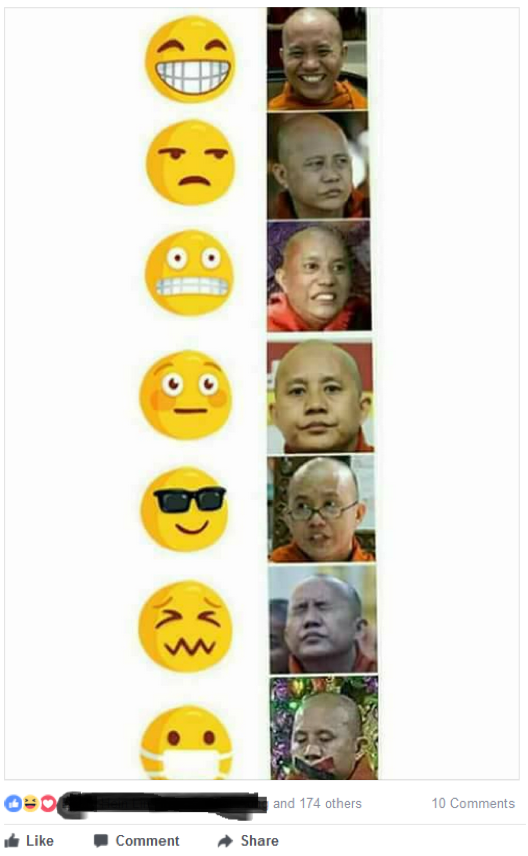

Within these groups, Myanmar teens mock human behavior and pop culture, debate politics, and even criticize religion, usually in a sassy, sarcastic tone.

Nan Wai, a 19-year-old Facebook user, says memes are popular among her friends. “Meme culture is really big now,” she said. “Everything gets turned into a meme—even politics. So they are almost like news—news in fun way. I have learned a lot from memes.”

T Tant, a Burmese writer, interprets Myanmar meme culture using the Carnivalesque theory of Russian literary critic Makhail Bakhtin. The theory describes literature that challenges dominant cultural norms without incurring repercussions by couching the critiques within scenes of absurdity, chaos, or humor. This is why jesters can rebuke kings and keep their heads.

According to T Tant, memes fill this role in ways that traditional forms of satire have not.

“There are some elements in the Carnivalesque theory that reflect today’s internet culture. Before memes, we had thangyat – satirical performances that critique mainstream culture,” he said.

Thangyat are traditionally performed during the Thingyan water festival. They were banned by the Myanmar government from 1988 to 2013, after which they continued to be censored.

“Thangyat are a form of expression that make fun of deformities and incongruities in social life. But they still adhere to some mainstream cultural standards, like [the theme of] expecting Burmese women to maintain their cultural practices,” T Tant said

“Thangyat may be free, but they have their limitations,” he added.

Meme culture, on the other hand, is unbridled absurdity. Memes give people the freedom to say whatever they want and to challenge mainstream beliefs without punishment, according to T Thant.

“Meme groups are following the same route as carnivals, where anything considered unacceptable in a society is exposed,” he said.

The carnivalesque chaos of meme culture has emboldened Myanmar’s youth to delve into previously forbidden territory.

“In our culture, anything controversial about religion is considered to be utmost sacrilege,” said T Tant. “Society is sensitive to any satire of religion. But in meme culture, the Buddha and images of Buddha are used to poke fun.”

Aung Phone Maw, a first-year mathematics student, said memes about religion allow people with different beliefs to grow accustomed to each other’s ideas, despite their disagreements.

“I made a meme making fun of snake pagodas, and my friend liked it,” he said. “He thought it was funny, but he was still convinced that there must be a spiritual connection between snakes and the pagodas in Myanmar.”

Another social force propelling cultural dissent through memes is the relative anonymity afforded by social media. Memes are a product of the ‘online disinhibition effect’, theorized by psychologist John Suler, which posits that social inhibitions that are normally present in face-to-face interactions tend to loosen in online interactions.

The ‘online disinhibition effect’ also explains why some memes end up going too far, entering territory that many would find mean or crude. The lack of physical interaction between online interlocutors makes empathy more difficult, leading to ever more rebellious memes.

But while memes offer freedom to express, they pose no immediate threat to the mainstream culture. T Tant says this is because no social institutions support the ideas presented in memes. Aung Phone Maw says meme culture is still very niche – many of his friends refuse to get involved.

Nonetheless, Myanmar’s meme culture is still an important refuge for people with bold ideas, and those who look closely can see its effects rippling quietly through the rest of society.

Aung Phone Maw said: “In the past, if we posted a meme about religion, people reacted by swearing in the comment thread. That rarely happens now.”

Aung Kaung Myat is a journalism student at Hong Kong University. He is an active member of Myanmar’s meme community.

Reader Interactions