Myanmar’s media has long been on the rack. On Wednesday, the situation worsened markedly when police formally charged two Reuters reporters with breaching the Official Secrets Act.

The case against Myanmar nationals Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo, which carries a maximum sentence of 14 years, follows their work on the Rohingya refugee crisis.

Hopes of a new dawn for free speech under the civilian government of Aung San Suu Kyi have been dashed.

At least 11 journalists were arrested in 2017 and dozens of non-media workers have been charged with online defamation since she took office the year before.

At the same time, rights groups say the Rohingya crisis has created a toxic atmosphere of self-censorship among the media.

Here are some of the other prominent legal cases involving the media and freedom of expression in recent months in Myanmar, which ranked 131st out of 180 countries in the 2017 World Press Freedom Index.

Jailed for flying drone

In October three journalists and their driver were arrested for flying a drone near parliament while working for Turkish broadcaster TRT.

The reporters, Myanmar national Aung Naing Soe, Malaysian journalist Mok Choy Lin and Singaporean cameraman Lau Hon Meng, were later jailed for two months along with their driver Hla Tin for violating a colonial-era aircraft act.

They were released in December shortly before finishing the sentence.

Observers linked the case to antipathy towards Turkey after its President Recep Tayyip Erdogan accused Myanmar of genocide against the Rohingya Muslim minority.

Facebook status

Investigative journalist Swe Win was arrested at Yangon’s airport in July and charged under the notorious 66(d) statute, which covers online defamation.

His case stemmed from Facebook comments in which he criticized a nationalist monk. Swe Win was released on bail but the case is continuing in the city of Mandalay.

Scores of writers, poets, journalists and civilians have been subject to 66(d) complaints, which have soared under Suu Kyi’s administration.

Complaints have been filed against critics of both Suu Kyi and army chief Min Aung Hlaing.

Drugs coverage

Three Myanmar journalists from The Irrawaddy and the Democratic Voice of Burma were arrested in June after reporting on a drug-burning ceremony.

The event took place in territory controlled by the rebel group the Ta’ang National Liberation Army.

The reporters were charged with unlawful association, a law used against supporters of Myanmar’s many ethnic armed organizations fighting for autonomy in border areas.

The case was eventually withdrawn but the reporters spent more than two months in jail, in what was seen as a warning against giving publicity to rebel groups.

Self-censorship?

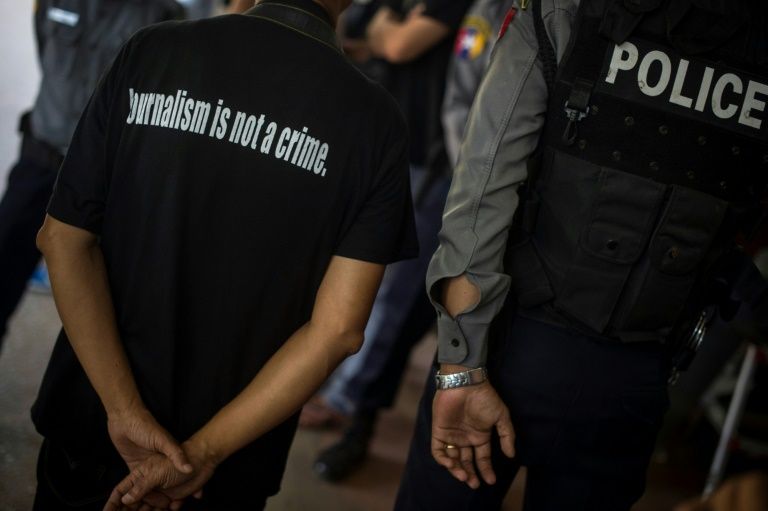

Photo: AFP / Ye Aung Thu

Pre-publication censorship was abolished in 2012. But articles critical of the security forces and senior officials still give editors reasons to be afraid.

Sometimes this reaches absurd heights: a satirist from The Voice newspaper was arrested in June along with his editor for publishing an essay gently mocking Myanmar’s failed efforts to make peace with ethnic armed groups.

Charges were eventually dropped against both of them.

Allegations of atrocities by security forces in Rakhine state also pose acute problems for Myanmar-based media.

They fear a backlash from the government and the Buddhist-majority public, who consider condemnation over the Rohingya crisis unfair and one-sided.

Several staff members at the Myanmar Times quit in protest at the firing of a colleague who had raised allegations of sexual assault against security forces in Rakhine.