Police Captain Moe Yan Naing has been hailed as a hero for exposing the police plot to trap Reuters journalists Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo. What few have talked about – what few, in fact, seem to realize – is that Moe Yan Naing himself was present with the perpetrators of the very massacre the Reuters journalists exposed.

On the morning of Sept. 2, 2017, Police Captain Moe Yan Naing slung a rifle over his shoulder as he trudged through the brush on the northern edge of Inn Din village. A few meters away from him were 10 Rohingya villagers – eight men and two high school boys – kneeling on the ground with their hands bound. What the police captain did next remains a mystery, but what is known is that a few moments later, the villagers were hacked with swords by their Buddhist neighbors, shot by Tatmadaw troops, and buried in a mass grave at the base of a nearby hill. Several were buried alive.

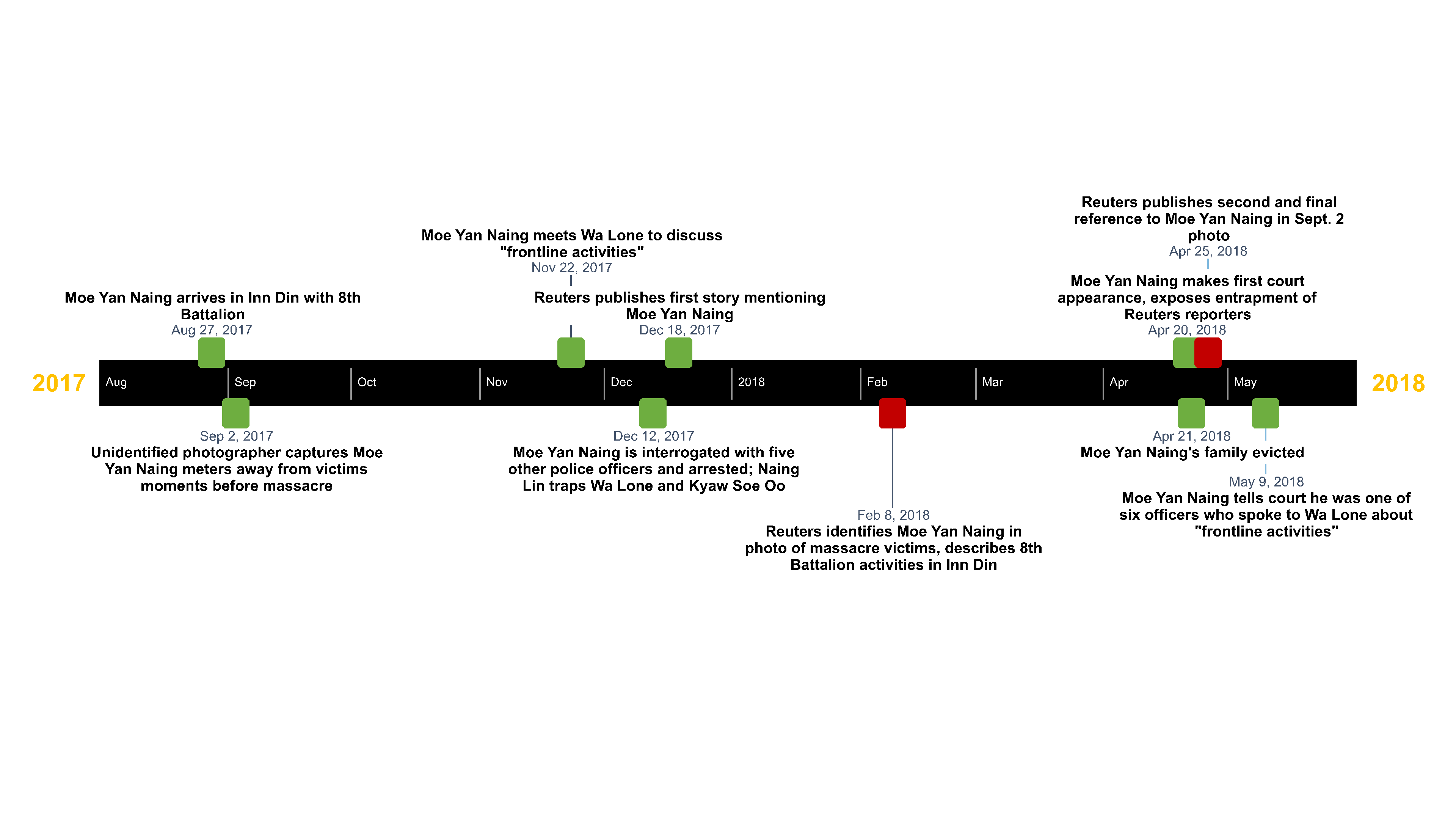

An unidentified photographer captured the scene moments before the killing began. Reuters published the photo on Feb. 8 and identified the police officer in the background, immortalizing Moe Yan Naing’s connection to the massacre for all who cared to look for it. However, few did so. Moe Yan Naing’s name would not make the news again until April 20, when his shocking testimony in a Yangon court exposed the plot to bring false charges against reporters Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo, who defied the Myanmar military and broke the story of the massacre.

Retribution was swift. The day after his testimony, Moe Yan Naing was sentenced to a year in prison for having given an interview to Wa Lone in November 2017, and his wife and children were evicted from their police housing unit. But equally swift was gratitude. Wa Lone thanked Moe Yan Naing for his testimony on the steps of the Insein Township courthouse, and Facebook users across Myanmar used the police officer’s face as their profile images. Journalists, rights defenders, and free speech advocates around the world hailed him for his bravery in exposing the trickery of the Myanmar war machine.

“Of course, he’s a hero,” said Hline Tint Zin Wai, founder and editor of the local news outlet Khit Thit Media and one of Moe Yan Naing’s most vocal supporters. “Most police always follow the instructions and orders coming from higher positions… Most government officials are afraid to speak the truth.”

When asked what he thought about Moe Yan Naing’s presence at the site of the massacre in Inn Din, the editor said the police captain’s past actions do not need to be reconciled with his reputation as a whistleblower.

“There are two sides,” he said. “On one side, government officials are scared to reveal the truth. In this climate, Moe Yan Naing risked and gave up his life and government position in order to speak the truth. This is what a hero does. However, as a serving police officer in Rakhine – killing for security reasons – he knows what he did.”

It is not clear that Moe Yan Naing did “kill for security reasons,” but what is clear is that many of his supporters are not interested in exploring the possibility that he did. In an essay that contains what might be the only reference to the police officer’s presence at the massacre site outside Reuters’s coverage, Myanmar Now chief editor Swe Win writes: “In one of the pictures [of the 10 Rohingya men], there’s a man in the background with a rifle strapped over his shoulder that looks just like Captain Moe Yan Naing.” Swe Win also alludes to the question of whether the police captain participated in the massacre or was merely present at the scene, but rather than seeking an answer, he concludes that Moe Yan Naing is an “unlikely hero” who “bet his life on an incomplete democratic experiment.”

The Myanmar-language media’s downplaying of Moe Yan Naing’s potential involvement in the massacre is mirrored by the way his story has been told in English. Articles that mention both the entrapment of the Reuters reporters and the Inn Din massacre fail to mention that Moe Yan Naing appears to have been instrumental in exposing both. Several foreign journalists and human rights defenders who have either published stories or tweeted about Moe Yan Naing told Coconuts that they had no idea that he was at the scene of the massacre, even though this information has been available to the public for months.

According to Reuters’s Feb. 8 exposé, Moe Yan Naing arrived in Inn Din village on or around Aug. 27 along with the rest of the paramilitary 8th Security Police Battalion, which was supporting the operations of the Tatmadaw’s 33rd Light Infantry Division. Over the next several days, the two units burned the Rohingya portion of the village, killing some villagers and sending hundreds fleeing to a nearby beach. After the initial assault, the 8th Battalion was assigned the task of looting the abandoned property and selling it to local Buddhists. The article even mentions that the 8th Battalion was led by a police officer with the rank of captain – the rank Moe Yan Naing holds – yet no one has asked publicly whether or not this was a reference to the man who would later become the star witness in the defense of the two journalists who broke the story.

Looking back at the piecemeal manner in which facts about Moe Yan Naing were made public, it is no surprise that his presence at the massacre site failed to grab readers’ attention. Everything we know about the police captain comes from the work of Wa Lone, Kyaw Soe Oo, and other Reuters reporters, who have not presented Moe Yan Naing’s story in such a way as to raise questions about his role the massacre. Out of a total of 14 Reuters articles that mention Moe Yan Naing’s name between Dec. 2017 and May 2018, only two refer to his appearance in the photo of the massacre victims. Even an essay by Reuters editor-at-large Harold Evans, whose entire thesis explores the visual significance of the photo, does not acknowledge the presence of the cop-turned-whistleblower or the questions it raises, the most significant being: What was Moe Yan Naing’s role in the massacre in Inn Din?

This question complicates the reputation of a man who has been praised for sacrificing his freedom to try to secure the freedom of two falsely accused journalists, but it does not necessarily pose a threat to that goal. Matthew Smith, the CEO of Fortify Rights, which has compiled a list of Myanmar officials who qualify for prosecution by the International Criminal Court for crimes against humanity, told Coconuts: “If Captain Moe Yang Naing was a physical perpetrator in the massacre or had effective control over those who carried out the killings, then he could be prosecuted. His possible role in the massacre or culpability for related crimes wouldn’t invalidate his testimony with regard to orders to arrest Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo. Those directly responsible for the massacre and the orders to arrest Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo are two separate issues.”

When asked for details on Moe Yan Naing’s actions in Inn Din, a spokesperson for Reuters declined to comment.

If the actions of Wa Lone, Kyaw Soe Oo, and Moe Yan Naing in the aftermath of the massacre convey any lesson, it is of the supreme importance of exposing the truth. Moe Yan Naing demonstrated this when he met with Wa Lone in a Yangon tea shop on Nov. 22, 2017, to offer him details of “police operations in Rakhine State.” He demonstrated it again on May 9, when he testified: “I know that Police Brigadier General Tin Ko Ko instructed Police Lance Corporal Naing Lin to give Wa Lone documents related to our frontline activities in order to have him arrested.”

With access to northern Rakhine State blocked to independent journalists and investigators since Myanmar’s destruction of Rohingya villages began, much of what we know about Inn Din and other massacres has had to come from complicated figures like Moe Yan Naing. Before he signed up for the entrapment of Wa Lone, even Lance Corporal Naing Lin had been in touch with the reporter as a potential source. Soe Chay, a Buddhist retired soldier and Inn Din resident who hacked a Rohingya man to death and dug the grave of the 10 massacre victims, gave Reuters the most detailed description of the mass killing and the events that led up to it. He even explained his decision to share his story with reporters, saying: “I want to be transparent on this case. I don’t want it to happen like that in future.”

As a journalistic source who is now serving time for his revelations, Moe Yan Naing has neither the freedom nor the obligation to explain what he did during the razing of Inn Din. However, as readers of news and seekers of truth, we all have the freedom and obligation to ask.

Additional reporting by Nay Paing. TOP PHOTO: Myanmar captain Moe Yan Naing waits outside the Insein Township courthouse before attending the ongoing trial of two detained journalists in Yangon on April 20, 2018. (Sai Aung MAIN / AFP)