Ko Min Htay is one of the most recognizable Burmese actors in the world. His role in the 2008 Hollywood blockbuster Rambo, the fourth film in the Sylvester Stallone series, remains a source of pride for him. But in recent days, it has also become a source of despair.

In the film, Ko Min Htay (formerly known as Maung Maung Khin) plays a villainous Burmese army officer who massacres and tortures Kayin villagers. When the officer kidnaps a group of Christian aid workers, Stallone’s Rambo swoops in and tears the Myanmar army to shreds with machine guns. The film ends with Rambo spilling Ko Min Htay’s guts onto the jungle floor.

But the Rambo star has only spent a few dozen days in his life acting. For most of his life, he was an anti-government insurgent. More recently, he has been a peacemaker. And today, in an odd marriage of truth and fiction, he is a prisoner of the Myanmar military.

He was arrested by the Myanmar Army late last year on charges of associating with the Kachin Independence Army (KIA), which has refused to sign the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement with the government. During a trial hearing at the end of March, a military officer serving as a witness for the prosecution claimed that his Rambo role defamed the Myanmar Army – an allegation that is likely to result in additional criminal charges.

But Ko Min Htay says his portrayal couldn’t possibly give the Myanmar army a bad name: the army does that by itself.

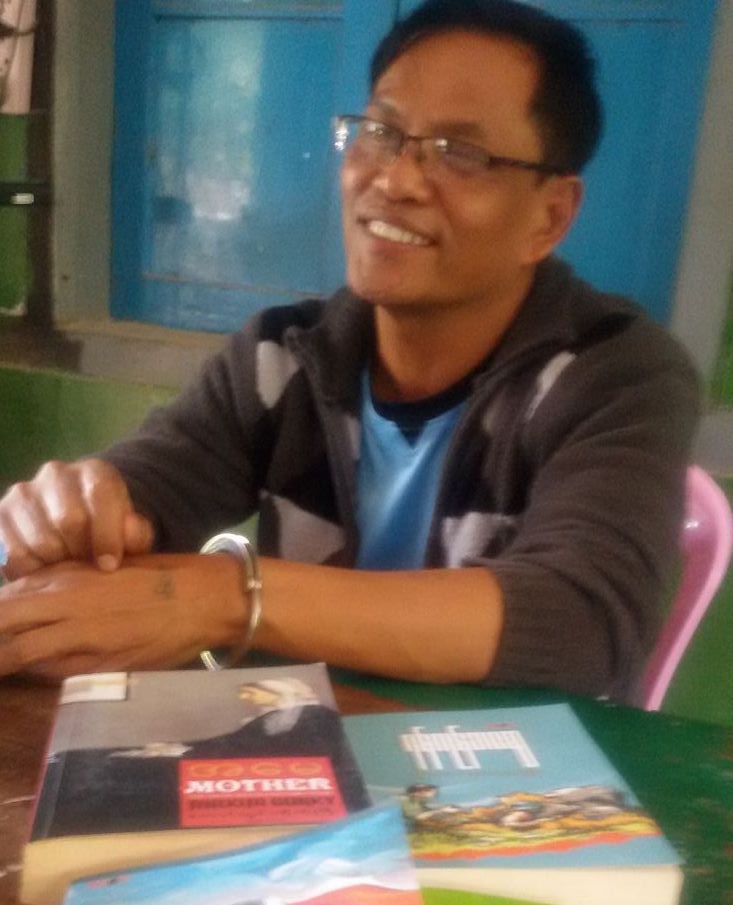

“The Burmese Army is way worse in real life,” he told Coconuts during an interview on the sidelines of the Union Peace Conference in September, when he was still a free man.

“In ethnic minority areas, where the media can’t reach, the army rapes and kills women. When they suspect someone of being in touch with a revolutionary group, they kill them. They don’t need to know the law. Their law is the gun. You know about the two Kachin teachers? Like that,” he said.

Ko Min Htay is a leading member of the All-Burma Students Democratic Front (ABSDF) – a once-armed rebel group formed by hundreds of student exiles in the wake of the 8888 Uprising. For most of his life, armed struggle against Myanmar’s military dictatorship was his profession.

“We didn’t decide to change from a student movement into an army. It was the Burma Army’s decision. They tried to arrest us and kill us. We had no choice. We needed to hold guns. So it wasn’t difficult to turn to armed struggle,” he said.

This struggle burned images of the enemy into Ko Min Htay’s memory and identity.

In 1992, he suffered a minor bullet injury to the head.

In 1993, he said, “I was sitting with one comrade by the roadside. We didn’t see the army coming. They came very close to us and started shooting. My friend was killed on the spot. I carried his body and buried it in the mud.”

It was enough to make him consider quitting altogether.

“I thought seriously about the future,” he said. “I tried to leave the revolution. I didn’t want to continue. But then I thought about my other comrades who are still in the revolution and who died in the revolution, and I couldn’t abandon them.”

But that decision was made for him in 1994, when the KIA, which had been arming and training the northern wing of the ABSDF, agreed to a ceasefire with the Myanmar government and instructed the ABSDF to give up its guns.

“The KIA told us, if you want to continue the revolution, you’ll have to do it elsewhere,” Ko Min Htay recounted.

The student rebels were thrust into a long period of vagrancy. They wandered between Myanmar’s various border areas, working hard jobs and preparing for the revolution to continue. By this time, the ABSDF was less of an army and more of a platform for workshops on human rights and federalism. Ko Min Htay became a central executive committee member sometime around 2000.

In 2007, he was in Chiang Mai, Thailand, where his wife, Daw Nan Yin, had been summoned years earlier to lead the Burmese Women’s Union. Ko Min Htay worked periodically as a voice actor on health education programs and dramas for BBC Radio, usually playing the villain. A friend from another rebel group told him a casting company was in town to prepare for a film that would be directed by Sylvester Stallone. They were looking for Burmese actors.

“Mostly Shan people tried out, but they couldn’t speak Burmese very well. I spoke Burmese very well, and I had experience as a soldier,” he said.

Ko Min Htay’s intimate knowledge of the Myanmar Army earned him a spot among six finalists whose tapes were sent to the US for review. When Stallone came to Thailand to choose his villain, it was Ko Min Htay.

“It wasn’t difficult to play a Burmese military officer. They were my enemy, so I studied them closely and tried to get information from them. So the character was very familiar to me. The only difficulty was that I was not really an actor,” he said.

He nailed the role, even suggesting edits to the script that he thought would make the film more realistic. Stallone accepted some, but rejected others, reminding Ko Min Htay: “It’s a movie, not real life.”

Even so, the Myanmar government has sometimes time felt the need to remind the public that the fictional film does not amount to evidence of real human rights violations.

After the film came out, the army sent officers to find Ko Min Htay in his hometown of Mogaung, Kachin State. The officers were told he hadn’t been there for decades.

Nine years later, Ko Min Htay is facing trial under Article 17(1) of the 1908 Unlawful Association Act for his association with the KIA, and he could be the next Myanmar artist to be prosecuted for a work of fiction. But he has no moral qualms over his actions.

Speaking to Coconuts through an intermediary from the Bamaw Prison in Kachin State yesterday, Ko Min Htay said: “I did not insult the army. Actually, I’ve been working with the army in the peace and national reconciliation process, which was initiated by the previous government [in 2015]. My organization signed the National Ceasefire Agreement in front of international witnesses.”

Why, then, is the army resurrecting the famous rebel’s past? Ko Min Htay believes it is personal.

“I’m here because of the feelings of the officers who arrested me. They have a long memory and are taking revenge on me. It’s not legal.”

Ko Min Htay says the ABSDF has petitioned State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi and Commander-in-Chief Senior General Min Aung Hlaing for his release. Both have abandoned their peace partner, saying they will proceed according to the law.

Despite the absurdity of his situation, Ko Min Htay remains hopeful. He still believes in Aung San Suu Kyi’s peace process, and plans to continue the struggle to change Myanmar’s constitution, promote democracy, and secure resettlement for the refugees of Myanmar’s many wars.

For the time being, however, the film star is forced to busy himself with catching mosquitoes and removing small stones from his rice in prison.

After relaying Ko Min Htay’s comments from prison, the intermediary asked Coconuts: “Can you send your story to Rambo? He needs to save Ko Min Htay.”