Three days ago, following a wave of anti-Muslim activity in Yangon, a body of Myanmar’s most senior monks ordered the dissolution of the radical Buddhist organization Ma Ba Tha. Unfortunately, a strike against an Islamophobic group is not the same as a step toward pluralism. Ma Ba Tha had been preparing for this moment for years, and now the movement may grow even stronger.

Less than a week before the State Sangha Maha Nayaka Committee ordered Ma Ba Tha to cease all activity and take down its signboards, the group’s leaders formed the Dhamma Vansanurakhitta Association (also spelled Dhamma Wantharnu Rakhita Association) as a new group for lay members of the movement.

We’ve seen this happen before. Toward the end of 2013, the committee banned the formation of groups associated with the 969 movement – previously Myanmar’s best-known instigators of anti-Muslim violence. When 969 groups were banned, the radical Mandalay monk Wirathu announced the formation of the Organization for the Protection of Nationalism and Religion – or Ma Ba Tha.

Like the Dhamma Vansanurakhitta Association, Ma Ba Tha was formed using a laypeople loophole in the Sangha committee’s ban.

“Technically, the venerable monks from the National Sangha Nayaka Committee did not oppose 969 groups,” Wirathu said in 2013. “The instructions and rules they issued are only related to monk associations. They do not have any impact on groups that include laypeople. We have the right to form this group independently.”

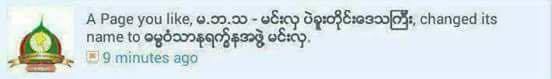

Earlier this week, Facebook pages for Ma Ba Tha chapters changed their names, rebranding themselves as Dhamma Vansanurakhitta Association pages.

Myanmar’s anti-Muslim movement has not gone anywhere.

Every move against Ma Ba Tha to date has been toothless. When the Sangha committee publicly “disowned” Ma Ba Tha in July 2016, it cited not the group’s hate speech but its failure to have been formed “in accordance with the basic Sangha rules”. The more recent ban only prohibits the use of the Ma Ba Tha name and symbols, not the dissemination of its ideology.

According to Burma Human Rights Network director Kyaw Win, the Sangha committee and the government are more interested in the optics of combatting Ma Ba Tha than in protecting minority citizens. The organization’s dissolution, like that of 969 before it, was only carried out while the group was in the international spotlight, he said.

Similarly, the NLD government, rather than displaying moral leadership and publicly promoting pluralism, has mostly been silent. The Protection of Race and Religion Laws, which were written by Ma Ba Tha and enacted by the previous government just before its term ended, remain firmly in place. Some of the laws have been interpreted as thinly veiled attempts to limit Myanmar’s Muslim population.

Furthermore, attempts to silence the anti-Muslim movement through the legal system are likely to have the unintended consequence of bestowing martyrdom. The same laws used to silence rights and democracy activists, like Section 19 of the Peaceful Procession and Peaceful Assembly Law and Section 505(b) of the Penal Code, have also been used to punish Ma Ba Tha sympathizers.

When the Ministry of Religious and Cultural Affairs ordered Wirathu to stop preaching in March, his supporters accused the government of bullying and violating the monk’s constitutional right to free speech.

Rather than deploying these toothless and arguably unconstitutional attempts to silence bigotry, Myanmar’s government and the Sangha committee should offer a message of pluralism that is louder and more convincing than bigotry.

Frontier has recently argued that this can be done by highlighting the moral leadership of Buddhists who exhibit love rather than fear or hatred.

Kyaw Win says pluralism can be used to appeal to those who want to see Myanmar grow into a democratic and economic success.

“The public should realize that religious extremism is the biggest obstacle to democratic reforms in a religiously and ethnically diverse country like Burma,” he said. “Religious extremism is the most dangerous toxin for the economic development for the country.”

“Every citizen should be considered a strength, not a threat.”

Reader Interactions