By Joel Elliott

Myanmar has a rich history of political cartooning. In the waning years of the military junta, an artist who writes under the pen name Aw Pi Kyeh (“Loudspeaker” in Burmese) took the pulse of a country riled by righteous indignation against the robber barons in power.

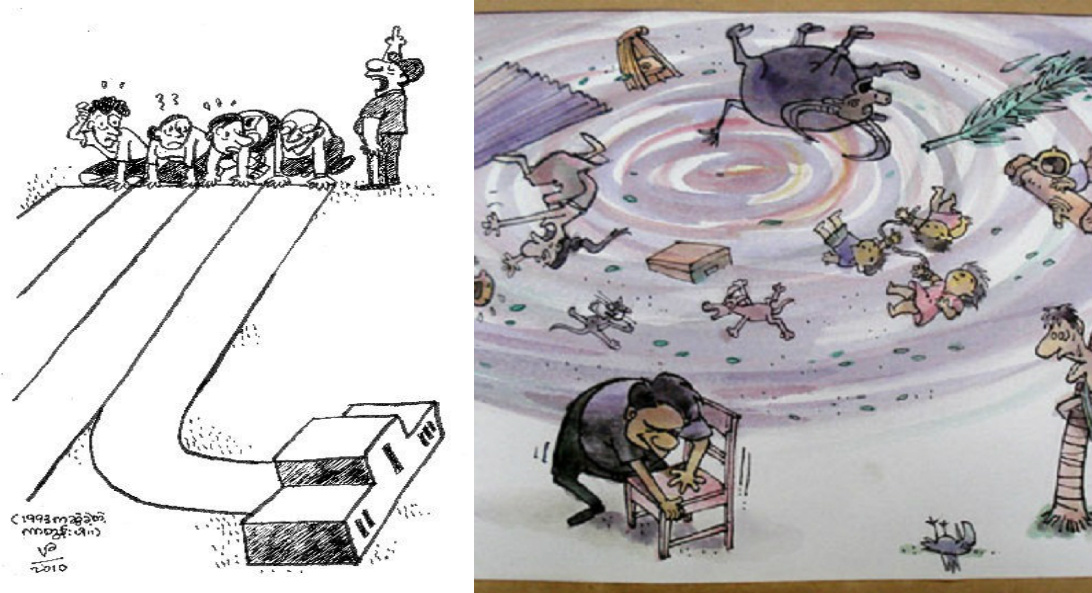

In one image, following the devastating Cyclone Nargis in 2008, a military leader secures his chair – the seat of his power – while ordinary people, livestock, and houses are blown away. In another, when the military’s USDP came to power in a 2010 election widely considered undemocratic, a cartoon shows runners at the starting mark of a sprint, with one lane leading directly to the top level of a podium – the outcome already pre-determined.

These days? A recent cartoon shows a crocodile, fresh from a slaughter on the other side of the river-bank, bawling in front of a news camera. “I had to leave my homeland,” it laments.

The “crocodile tears” analogy is as crystal clear as it is cliché: the land he just left is Rakhine State in Western Myanmar, the slaughtered animals are Rakhine Buddhists and other ethnic groups, the crocodile itself a Rohingya, standing in for the 600,000 who have fled over the last two months.

For the audience to whom the cartoon caters, the crocodile’s claim of Myanmar as his homeland is so instantly preposterous it’s not even worth addressing.

This abrupt about-face – from punching up to punching down – is just one of many readily available responses on social media to any international outlets that dare criticize the military, State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi, or Myanmar as a whole.

When the world thinks of the hate speech that stirs up venom toward the Rohingya, the first name to come to mind is provocateur monk U Wirathu, whose comparisons of Muslims to dogs have made him into Myanmar’s version of alt-right populists in America.

Far less attention is paid to the myriad public voices who, like Aw Pi Kyeh, once spoke truth to power but now preach hate against the powerless.

These voices are not coming from the fringe, but from the most progressive elements of Myanmar society: human rights defenders, democracy advocates, interfaith leaders, and former dissidents under the military junta.

I talked to Myawady Sayadaw, abbot of the eponymous monastery outside Mandalay, who protested during the Saffron Revolution in 2007 and has since represented Theravada Buddhism around the world at various peace conferences and workshops. He takes a kind of self-contented pride in his opposition toward the Association for the Protection of Race and Religion, known locally as MaBaTha – a Buddhist organization that gives a platform to ultra-nationalist voices like Wirathu’s.

He speaks eloquently against “hate speech” and in favor of “dialogue,” words that stand out because they have no proper Burmese equivalent, presumably borrowed from English via International NGOs and human rights groups.

But when asked whether such hate speech contributes to the negative perception of the Rohingya, he rapidly shifts gears: “That situation is different.”

While acknowledging that there are two sides to the story, he accepts as fact that they are “not refugees, they’re invaders.” Like the cartoonist, he assumes there’s no possibility of a third option, of recognizing that Myanmar is the only home ever known to the majority of Rohingya.

“[Muslims] need to take care of themselves.” They have the “duty…to [gain] the trust of other countries,” as a result of their historical actions, Myawady Sayadaw explains.

This oft-cited reference to history goes back more than half a millennium, to the Buddhists who were formerly living in now predominantly Muslim countries like Afghanistan and Indonesia. These days, the abbot and others connect these incidents to Islamic terror attacks in modern-day Europe.

This is the common narrative that undergirds both extremist and moderate Buddhist elements in Myanmar. It’s a vast and one-sided view through which centuries of imperial kingdoms of various religions are distilled down to a single story: Buddhism under siege by Islam.

Sometimes, more subtle forms of discrimination spill over into genocidal language.

Sitagu Sayadaw is one of the most famous Buddhist teachers in all of Myanmar, and well known both for his charitable work and his global interfaith activities.

He recently gave a speech in which he said the Tatmadaw (the military) and Sangha (the collective word for Buddhist monks) “must unite,” followed by a grim and ominous recounting of the apocryphal tale of King Dutugemunu of Sri Lanka.

After slaughtering countless Hindu Tamils, the king was advised not to worry because he had only killed “one and a half real human beings,” the number, among his victims, of those who had fully followed the Buddha’s Five Precepts.

Despite the way religion fuels these narratives, there is a widespread conviction that the Rohingya – the largest single Muslim minority group in Myanmar – are not victims of Islamophobia. Rather, the language is one of borders and security.

“I think it’s an issue of migration”, says Thawng Thang, who works for the Judson Research Center of the Myanmar Institute of Theology, an interfaith organization.

That perspective is hardly confined to the Buddhist clergy, and is, in fact, dominant among all religious and secular groups in Myanmar, even non-Rohingya Muslims.

Matthew Walton, the Aung San Suu Kyi Senior Research Fellow in Modern Burmese Studies at Oxford University puts it bluntly: “I don’t think, in the history of modern Burma, there has ever been an issue that has united the population as widely and broadly as hatred of the Rohingya… This crosses ethnic lines, it crosses class lines, it crosses religious lines.”

Among the most revered of human rights groups in Myanmar is 88 Generation – activists who organized the nearly-successful uprising of 1988, many of whom were jailed by the military junta for up to 20 years, and released in the general amnesty in 2012.

But when violence flared up that same year in Rakhine State, despite the disproportionate attacks on Rohingya, the group was quick to blame the violence on “illegal immigrants from Bangladesh,” who are “absolutely not related to any ethnicity in Myanmar.”

Ko Mya Aye, a Muslim and prominent leader of the group, blamed the Rohingya for trying to “bond” with other Muslims, cynically dismissing international support as “a crowd-pleasing issue that can generate funds,” and condemning only the violence against Rakhine Buddhists.

At the same time, in perhaps the most insidious example of how the language of human rights and apartheid can co-exist in the same breath, famed dissident and National League for Democracy (NLD) leader U Win Tin called for protection of the Rohingya’s rights while simultaneously entertaining the idea that “we might have to confine them some place, like a camp.”

Five years later, as U Win Tin’s suggestion is well on its way to becoming a reality, nothing much has changed. Amid the recent violence and displacement, the 88 Generation echoed similar sentiments.

“The government is working hard for democratic transition. It would be wrong to criticize or weaken them,” said U Jimmy, a veteran member of the group’s leadership.

In an interview, Ko Mya Aye comes off softer, suggesting that if any of the Rohingya are eligible for citizenship, “they should be given [it],” and that they could be included among the official 135 ethnic groups of Myanmar, if “historians on both sides” and “the people” can accept them. That caveat, of course, represents an impossibility amid the current popular resentment.

It might be tempting to suggest that former radicals and activists have simply become too incorporated into the current halls of power, but it was only two years ago that Aung San Suu Kyi’s NLD party was rejecting the bid of 88 leaders like Ko Mya Aye, Ko Ko Gyi, and Min Ko Naing to sit as representatives.

Indeed, as outsiders who, like Suu Kyi herself, command broad respect and legitimacy through the sacrifices they’ve made in the past, they are perfectly positioned to effect change.

As for Suu Kyi, her NLD recently staged interfaith rallies, where thousands gathered in Myanmar’s major cities. While many religious leaders spoke admirably of general peace and a resolution to conflict (without including or mentioning the Rohingya by name), the real purpose seemed to be to bolster support for Suu Kyi amid growing international condemnation.

“This event shows Myanmar is a country with the people of different faith[s] living in harmony,” said U Phyo Min Thein, Yangon Region’s chief minister.

According to Harry Myo Lin, head of the interfaith organization Seagull, the message was “that we are getting along and we don’t need others to talk about us.” He personally believes that Suu Kyi does not share the belligerent perspective of the Tatmadaw towards the Rohingya, but is at a loss as to why she doesn’t speak up.

“She can easily call for peace. She can easily go against hatred. Because she has such moral support, she can easily influence a lot of her supporters,” he said.

If this widely accepted discrimination amid a massive ethnic-cleansing campaign is surprising to those in the West, it may be because there’s a tendency to associate the move towards a liberal democracy with greater democratic freedoms for everyone.

But what distinguishes many genocidal conditions in world history since the 20th century is not the complete absence of human rights amid dictatorships, but the relentless march of “progress” and “development” under the banner of nationalism, one that routinely prizes ethnic or religious homogeneity

In the Ottoman Empire at the turn of the century, the Young Turks and the Committee for Union and Progress (CUP) ushered in a slew of military and political reforms to counter the absolute monarchy of the sultan. But in the ensuing power struggle, the Three Pashas wrested control away from the liberal elements of the party, the country joined World War I on the side of the Central Powers, and within a few years, nearly 1.5 million Armenians were massacred or displaced.

Likewise, when the one-party Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia dissolved in the early ’90s amidst multi-party elections in the individual republics, ethnic cleansing on a massive scale ensued.

In Myanmar, more systematic classification has led to both increased recognition of the various ethnic groups as well as the disenfranchisement of the Rohingya – from the 1982 Citizenship laws, to 2015, when the Rohingya’s temporary citizenship cards (which allowed them the right to vote) were revoked. That move, incidentally, came as the result of massive public pressure, not military strong-arming.

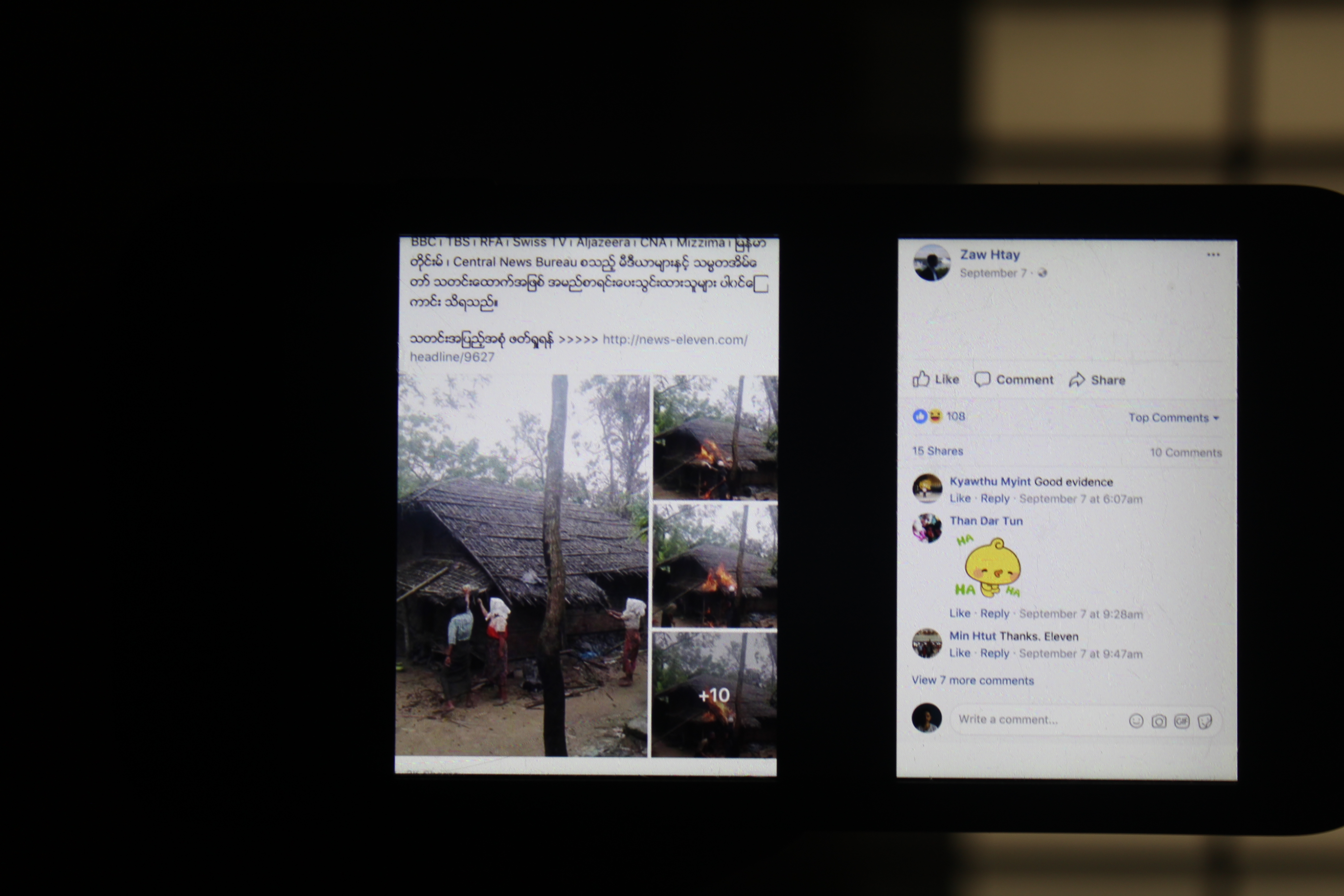

Today, Myanmar has achieved the “perfect storm” conditions necessary for ethnic cleansing: a military that still doesn’t answer to civilians, a wave of populist anger, and the growth of toxic fake news in the wake of a rapid telecommunications revolution.

In the Ayeyawady Basin, where major cities like Yangon and Mandalay are situated, some 1,000 kilometers of inhospitable mountain terrain away from the violence in Rakhine State, words can seem futile. Many Burmese people I’ve spoken to evince a grim fatalism with regards to the military and its actions.

Myanmar’s activists are hardly apologists for rape and murder, but focusing on tepid academic debates centered on whether or not “Rohingya” is a wholly distinct ethnic category separate from “Bengali” only serves to mask the horror of the atrocities taking place in Rakhine State.

It’s helpful to remember that the vast majority of Rohingya are less interested in preserving their title than they are in having access to basic food, shelter, healthcare, movement, and education – all needs that have been periodically denied to them.

For U Kyaw Min, the former Rohingya MP and current political activist, the name doesn’t even matter. “Bengali, Rohingya, Muslim… it’s not a big problem. With any identity, we want full citizenship [like] other races in this country.”

Thankfully, some organizations have started speaking out for these basic rights. Thet Swe Win, of the Center for Youth and Social Harmony, and Moe Thway, of Generation Wave, are two activists who have both begun boldly mentioning the Rohingya by name as part of a broader campaign of rethinking the country’s future.

This holistic way of viewing the situation implicitly acknowledges that the problem is not primarily about religion itself, but rather the poisonous interaction of various divisions of ethnicity, culture, and language along with religion. Both of these organizations target the country’s youth, believing that younger generations can more easily shed the prejudice of their forebears.

According to Thet Swe Win, the older generation’s lack of investment into understanding and ending the persecution of the Rohingya stems from a misunderstanding of the nature of democracy: “[They] don’t think democracy is a process… they think [it] is something fallen from the sky.”

“Suu Kyi, 88 Generation – we don’t believe that they can finish the process,” says Moe Thway. “Of course, they are the initiators, and they are the pioneers, and they are the leaders. But the struggle is still long. So, we need new leadership.”

A good example of one such young leader is a monk who goes by the name “Ashin Zero” a name that reflects both a Buddhist belief in the disappearance of the ego and the anonymity with which he’s had to mask himself online.

“When I posted with my real account, some people threatened to kill me,” he says.

Because of these risks, many of those Burmese who do want to help the Rohingya often do so in secret, quietly compiling data for international groups, for example. Eventually, they hope, the trickle of facts will leave a dent in the public consciousness.

The process of a change in mindset will span years, if not generations. It’s hard to say if the Rohingya, a people without a country, have that long.