A tiny country bursting with diverse cultures, Singapore is home to more than 1,000 Taoist and Buddhist temples mainly dedicated to its large Chinese community, with one of the earliest built not long after the British established a port here in the early 1800s.

The Fuk Tak Chi temple, for example, was built in the 1820s by a group of Cantonese and Hakka-speaking Chinese settlers in the middle of what is now Singapore’s business district. The temple’s signature architectural style, which includes floral roof motifs, is reminiscent of temples in Fujian, China, and stands out among the row of shophouses along Telok Ayer Street near Chinatown.

Taken together, the city’s tapestry of Chinese temples are easily mistaken for a mismatched and motley collection of competing styles. But look deeper and find they speak to the identities of those who made Singapore home, bringing their architecture and preferences with them to be shaped by a common community sometimes at odds with itself. We talked to a temple guru about their history, why they differ architecturally, how they came to be, and where to find them today.

Beyond being places of worship, these elaborately decorated monuments are also places for people to socialize within the different Chinese groups and clans. Singapore is predominantly made up of Chinese, whose predecessors came from families that spoke different dialects, with Hokkien being the most common, followed by Teochew, Cantonese, Hakka, and many others. Different dialects have different tones and pitches, with Mandarin having four tone levels, while Hokkien and Teochew have eight, Hakka six, and Cantonese nine.

These days, Chinese Singaporeans have largely homogenized to speak Mandarin, with other dialects obliterated from television and radio programs. Back in China, the different dialect groups do not integrate as much as they do in Singapore, with the Hokkien Chinese mostly based out of Fujian, and the Teochew Chinese from Guangdong province.

The mingling between different dialect groups is why many of Singapore’s traditional Chinese temples do not strictly follow the styles of the different provinces and often incorporate designs from parts of China. The Fuk Tak Chi temple itself was designed with an exterior that followed Hokkien temples in Fujian, even though it was not built by that community.

“There are subtle differences and aesthetic preferences within the Chinese and they are not as homogenous,” a local academic who spent a decade studying architectural conservation in Singapore told Coconuts recently. Professor Yeo Kang Shua from the Singapore University of Technology and Design was also involved in the restoration of the Teochew-style Yueh Hai Ching several meters from Fuk Tak Chi and the Hokkien-style Hong San See temple in River Valley.

“There are varied preferences for each dialect group,” Yeo added. “But at the same time, we are also rojak (mixed). Most of the buildings we have are influenced by more than one culture, subculture and regional differences.”

The different dialect groups also had to work together to sustain the rising economy of the 19th century, which meant that the Hokkien Chinese sometimes had to rely on non-Hokkien temple builders, or the Cantonese Chinese having to expand its temple-making business to other groups for more revenue.

“In Singapore, we are so small. If we are temple builders, it’s economically difficult to only serve one particular dialect group. You want a wider customer base, unlike in China when they engage only Hokkien builders for Hokkien temples, for example,” Yeo said.

Singapore’s oldest temples were also built amid tumultuous times, with violent clashes regularly breaking out between business rivals, mostly among the two biggest groups here – the Hokkiens and Teochews. A rivalry between spice merchants led to a massive riot in the 1850s that killed hundreds of people and damaged homes. The Fuk Tak Chi temple, for example, is said to have adopted Hokkien architecture to avoid unnecessary tension.

But that’s a nearly forgotten past and clashes are no longer part of Singapore’s reality. The award-winning professor, who has gotten a UNESCO nod for his work, also said that nobody cares about who builds their temples anymore.

“In the contemporary world, no one cares about the dialect styles because of the rise and popularization of reinforced concrete,” the author of the Homogeneously heterogeneous? The Diversity of Traditional Chinese Architecture in Singapore said. Other modern temples that have emerged in Singapore in recent years include the contemporary-style Mahabodhi in Bukit Timah.

Since early Chinese immigrants settled along the Singapore River, where British colonialist Stamford Raffles had set up a trading settlement, old Chinese temples are peppered along this route. Along the same Telok Ayer Street, just a few minutes walk from Marina Bay, the Fuk Tak Chi shares the area with neighboring temples Thian Hock Keng, which was built in the 1840s by Hokkien settlers, and the Yueh Hai Ching temple, which was built in the late 1800s by Teochew settlers. In downtown Singapore alone, there are approximately 15 temples. As housing developed in other parts of Singapore, temples gradually mushroomed in those areas as well.

The various Chinese temple designs follow five broad architectural styles inspired by the temples of different Chinese cities and provinces. The Hokkiens love a majestic temple and follow the styles of Quanzhou and Zhangzhou cities, which means high terracotta roofs and courtyards. The Teochews prefer the intricate look of Chaozhou city’s temples, which normally have grey roof tiles that are decorated heavily with ceramic artworks. The Hakkas tend to lean toward tall, towering temples, while the Hokchew-speaking minority prefer the style of sprawling temples from Fuzhou city. Meanwhile, the Cantonese are less conspicuous with their temples and prefer small-sized buildings and monochromatic colors.

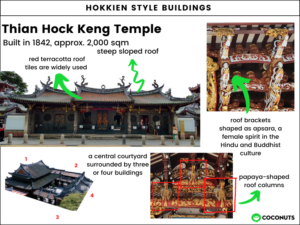

Hokkien-style buildings

Hokkien style temples like the 2,000-square meter Thian Hock Keng typically have a central courtyard surrounded by three or four buildings topped with steep-sloped roofs of red terracotta bricks. The roofs are designed to allow rainwater to flow off the building and its roof ridges extend outward like a swallow’s tail.

Figures of the female spirit apsara adorn the spaces underneath the roofs as well as papaya or pumpkin-shaped roof columns.

Other temples established by the Hokkiens: Hong San See temple, Tan Si Chong Su temple

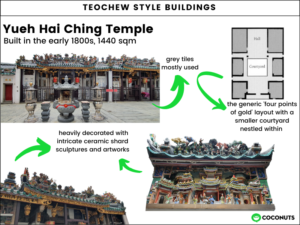

Teochew-style buildings

Teochew-style temples like the 1,400-square meter Yueh Hai Ching temple barely use red tiles and are heavily decorated with intricate porcelain shard works. Just like Hokkien-style temples, the Teochews also build their temples with a smaller courtyard surrounded by multiple buildings. They call the courtyard “four points of gold,” symbolizing security and union of the families occupying the space.

Walls and roofs of the Yueh Hai Ching temple are also plastered with hundreds of ceramic shard sculptures and artworks.

Other temples established by the Teochews: Tong Sian Tng temple, Kwan Im Thong Hood Cho temple

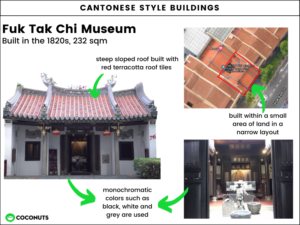

Cantonese-style buildings

Cantonese style buildings like the 200 square meter Fuk Tak Chi museum are typically built on a small and narrow piece of land sandwiched in between buildings and have at least two courtyards.

The Fuk Tak Chi also has very few windows and doors, and sticks to mundane monochromatic colors like black, white, and grey.

Other temples established by the Cantonese: Mun San Fook Tuck Chee temple, Zhun Ti Gong temple

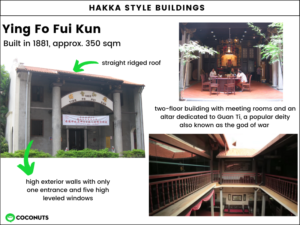

Hakka-style buildings

Hakka style buildings take a brutalist spin on Chinese architecture by using soaring concrete blocks. The design was inspired by 17th-century China, when the Hakkas of the Fujian and Guangdong provinces had to protect themselves from clashes with neighbors.

The Ying Fo Fui Kun clan association at Telok Ayer Street paid homage to this when it was built in the late 1800s. The ground floor houses meeting and administration rooms while the upper level is occupied by an altar for the Guan Ti deity also known as the god of war.

Other temples established by the Hakkas: Hock Teck See temple, Tian Shou Tang Lu Zu Gong temple

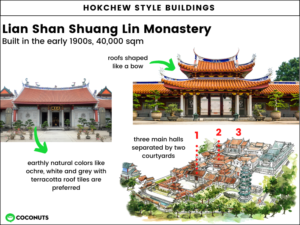

Hokchew-style buildings

Hokchew temples are a sight to behold. These temples stretch out over large spaces and can be detected from far with their amber terracotta roofs. They comprise multiple buildings and have at least two big courtyards.

The 40,000 square meter Lian Shan Shuan Lin Monastery in Toa Payoh was designed this way when it was built in the early ‘90s.

Other temples established by the Hokchews: Poh Tiong Kiong Temple, Cheow Leng Beo temple

Other stories you should check out:

Watch Singapore rise and fall in athletic filmmaker’s 8-year time lapse

In pictures: Journey to the new Apple’s core at Marina Bay Sands