“They have used the language of resistance in America, but we thankfully are in a very different situation.”

“Older Singaporeans will recall the Black and White Minstrel Show, which was quite acceptable back in the 1960s and 1970s.”

“’Brownface east’ does not exist.”

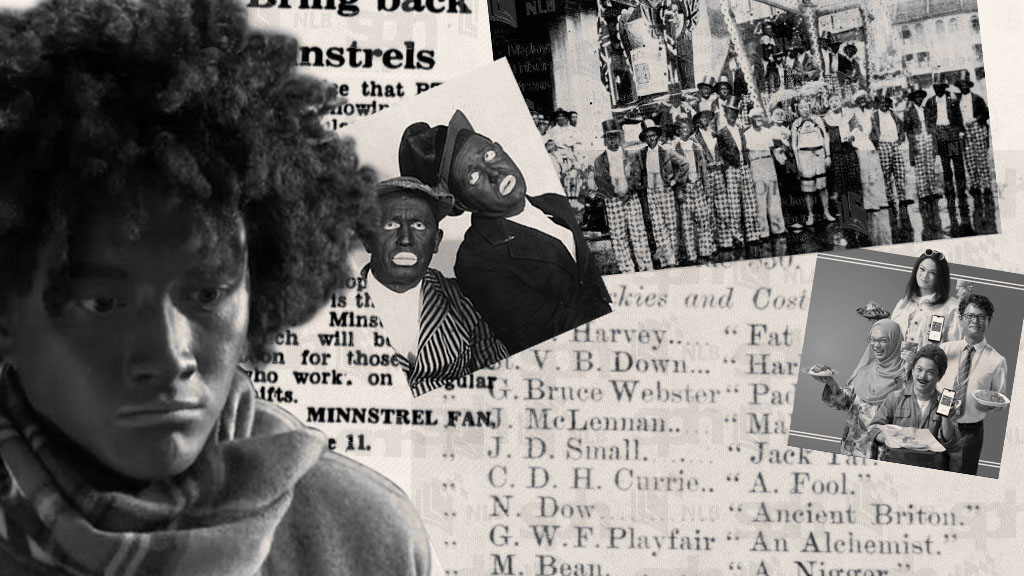

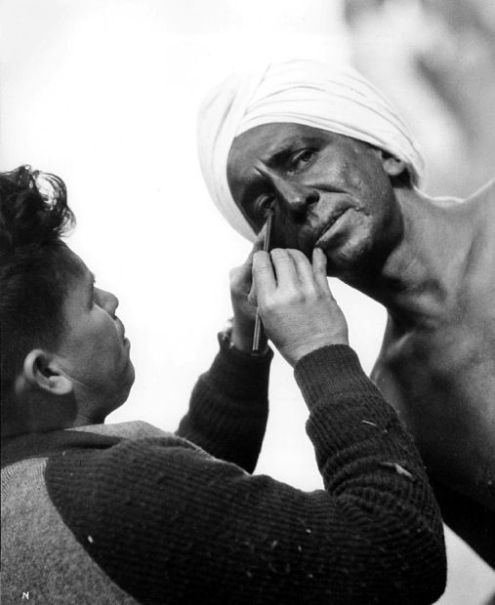

In the weeks since the uproar over the decision to have Chinese-Singaporean actor Dennis Chew darken his skin to play an Indian for laughs in a national ad campaign, I’ve seen a lot of people attempt to make a distinction between blackface and brownface.

Blackface is an American thing. It’s something white people do. It’s offensive only because of that country’s long history of slavery.

Brownface? Eh. It’s harmless. Minorities in Singapore are just being sensitive.

But Singapore was never an isolated island, and racism is never about an isolated incident. The idea that we somehow went from a British settlement to an independent nation without ever being cognizant of racism seemed absurd to me. Watching Singapore celebrate her bicentennial this past weekend, I wondered why we hear only the good things about our colonial legacy, yet all our conversations about race seem to start with Lee Kuan Yew.

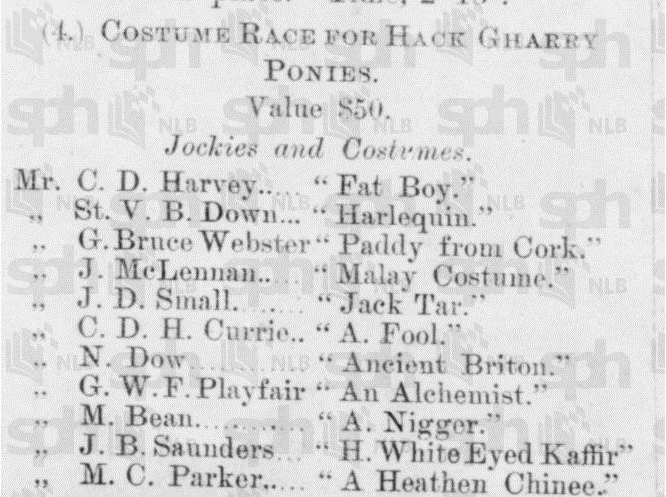

In 1887, the statue of Stamford Raffles we’re all familiar with was first unveiled at the Queen’s Jubilee. One day later, there was Jubilee Race Meeting at the Sporting Club (what the Singapore Turf Club was called in those days). One of the events was a Costume Race in which British jockeys were identified as “A N*****”,” “White Eyed K*****,” “A Heathen Chinee,” and in “Malay Costume.”

In 1897, Lim Boon Keng founded the Chinese Philomathic Society with the intention of studying English literature, Western music, and the Chinese language. It was a Philomathic Society concert just a few years later where a Song Ong Joo was praised for giving a “particularly successful impersonation of a negro minstrel.”

In 1925, a Raffles Institution student put on a performance, singing and dancing as a “n***** minstrel” during a school concert. Famous alumni who would’ve been students at RI at that time include Yusof Ishak (our first president, 1959), David Marshall (our first chief minister, 1955), Choor Singh Sidhu (Supreme Court judge, 1963) and Lim Bo Seng.

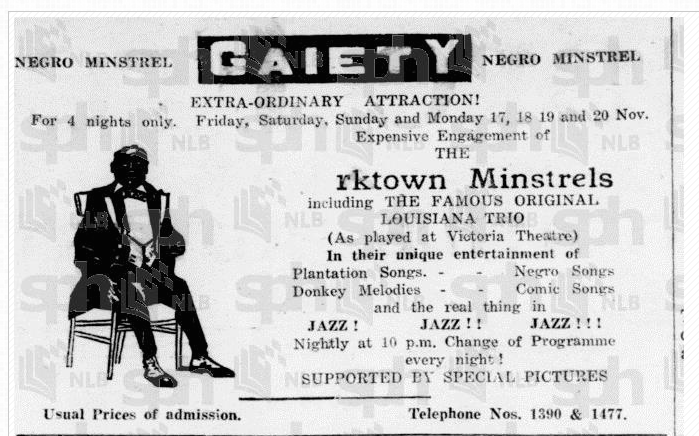

By the 1930s, our forefathers were active participants and consumers of minstrel entertainment. Minstrel parties were common, where “locals used to go around with their faces painted with charcoal.” Minstrel groups were invited to play at weddings, birthday parties, and fundraising events. Almost every neighborhood had its own group — the Wales Minstrels from Amber Road, the Merrylads in Katong, the Cornwall Minstrels from the Cornwall Street neighborhood, the Gaylads from Geylang.

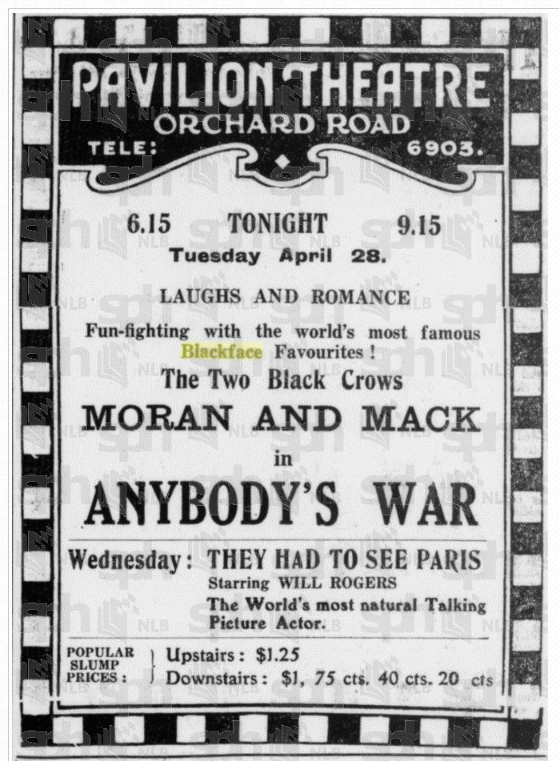

American and British versions of the shows were also imported, with live theater performances at the Victoria Theatre and movies at the Pavilion Theatre in Orchard Road.

It hardly comes as a surprise then, that the “Black and White Minstrel Show” was popular here. Our parents, grandparents and great-grandparents grew up with minstrelsy as entertainment, ignoring the fact that anti-racist organizations around the world were calling for the end of the shows. There are no less than three articles in The Straits Times between 1964 and 1973 pointing out the offensiveness of blackface and reporting calls for bans in London and New Zealand.

Still, the shows remained popular in Singapore through the late 1980s. Articles and reviews locally described them as “good family entertainment,” with letters to the editor written in dismay when they were taken off the TV airwaves in the 1970s. “Black and white minstrel” performances could be taken in live at least as late as 1987.

Why does any of this matter? I think it’s important to acknowledge that what we’ve seen in recent weeks isn’t new, that this isn’t just overly sensitive “social justice warriors bringing America’s racism problem and language of resistance.” We may be a little red dot, but we’ve always been globally connected.

Were the schoolboys who grew up to be our leaders told that the “n-word” was a painful slur? Were our parents and grandparents taught the history of slavery and racial segregation? Did they think it was right? Or did it simply not matter as long as they got a few laughs out of it?

I personally find it hard to believe a century’s worth of racist entertainment could have absolutely no effect on our own attitudes and prejudices.

Now in Injia’s sunny clime,

Where I used to spend my time

A-servin’ of ’Er Majesty the Queen,

Of all them blackfaced crew

The finest man I knew

Was our regimental bhisti, Gunga Din

- Gunga Din, Rudyard Kipling

In 1939, Gunga Din, a movie based on the eponymous poem, featured an American actor, Sam Jaffe, in brownface. The film was banned in Singapore due to concerns about “racial antipathy” and riots in some parts of India and Malaya. After a successful appeal, it began showing over the Easter weekend in 1940. There were rave reviews, until the film abruptly stopped showing. Apparently, “local Indians… made representations to the Government, taking objection to the screening of the film in this country on racial and religious grounds.”

Nearly 50 years later, the 1986 comedy Short Circuit featured white American actor Fisher Stevens donning brownface to play an Indian character, complete with “Indian accent.” Reviews in both The Straits Times and Business Times took note of the unfortunate stereotyping, with BT calling it “tiresome and offensive.”

But when it comes to conversations about our own home-grown racism, every single instance seems to end with “Are we allowed to talk about this?”

It follows a familiar template. Broad statements are made about the importance of racial and religious harmony, while specific statements are made about how a particular incident may have been “insensitive.” What’s consistently missing, however, is a frank discussion of the broader issues of discrimination, systemic racism, dehumanization.

A recent Twitter thread by Visakan Veerasamy tracks a number of separate instances of brownface in Singapore in this decade, all of which saw no penalties for anyone involved.

It's time for a History of Singaporean Chinese people in Brownface

2012 UOB bollywood-themed party https://t.co/mqlMPe5VpT pic.twitter.com/lhuF0VUyUp

— Visakan Veerasamy (@visakanv) July 30, 2019

One instance that did see a fine, covered at the time by Coconuts Singapore, involved an actor donning blackface in the Toggle series I Want to Be a Star.

That incident resulted in a S$5,500 fine for Mediacorp, with the Info-communications Media Development Authority (IMDA) saying that the episode was assessed to be “racially insensitive” and “constituted racial stereotyping that might offend certain segments of the community.”

Since the uproar over the E-Pay ad, for which there will be no fine, Minister for Home Affairs K. Shanmugam, the Singapore Police Force, the Attorney-General’s Chambers, the IMDA, and the Advertising Standards Authority of Singapore have all stepped forward to explain that while brownfacing may have been “insensitive,” it wasn’t illegal.

If you were looking for stronger condemnations, those were saved for the scathing rap parody video created by Singaporean siblings Preeti and Subhas Nair as a reply to the E-Pay controversy.

Within days of that video’s release, Shanmugam — who in March banned a concert by Swedish “black metal” band Watain and somehow managed to drag race into that — was calling the rappers out for crossing the line.

Between Preetipls’ rap and the Watain concert, Shanmugam has shown that he, like many local politicians, is far more outraged by four-letter words and middle fingers than brownface.

In fact, the one thing we haven’t seen from any of the actors in this tawdry drama is a strong, unequivocal condemnation of brownface.

“I’m sorry your feelings were hurt” is the ultimate non-apology apology, but time and time again it’s the only one offered when these situations rear their ugly heads.

We’re left to wonder how long will it take for someone to finally take ownership not for the fallout but for the act itself, how long until someone can bring themselves to say three simple words: brownface is wrong.