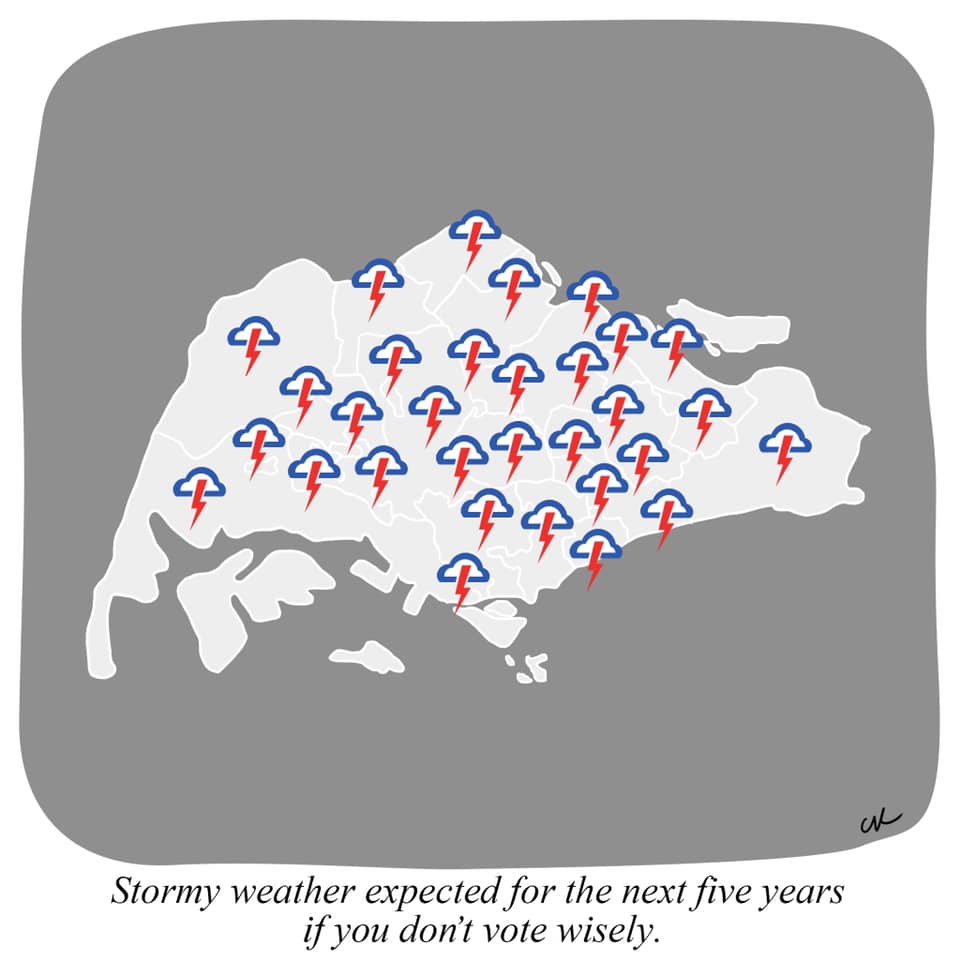

When Teo Yu Sheng’s cartoon started going viral, he began to worry. Posted to Instagram and Facebook on July 6, the six-panel comic depicts a unicorn questioning the deputy prime minister’s declaration that older Singaporeans aren’t ready for a non-Chinese leader. When the unicorn asks if this can be considered racist, he’s cut off by another character, who threatens to call the police. Teo nervously watched the likes and shares on the post accumulate, wondering if he had crossed the line and was about to get into a whole lot of trouble.

Teo runs Heckin’ Unicorn, a Singapore-based LGBTQ+ apparel company. The brand’s social media pages are usually awash with cute socks and enamel pins. Semi-regularly, though, a comic will appear. Initially, Teo had had no plans to draw cartoons; the idea of a comic was suggested by a friend as a means to drive customers to his online shop during the first weeks of the coronavirus pandemic. But in explaining and sometimes mocking certain conservative Singaporean attitudes, especially those directed at the queer community, his comics get thousands of likes and attract a lot of attention. The recent Mediacorp apology for harmful depictions of gay characters onscreen? A Heckin’ Unicorn cartoon started that conversation.

To date, nobody has called the police on Teo or his work. “I drew the line on the floor for myself,” he said – deciding what subject material is okay to discuss in his comics, how to surface these topics in a factual and respectful way. Every Singaporean cartoonist working independently to put political cartoons on social media — and there aren’t many of them — has to run the same mental cost-benefit analysis before hitting “post.”

Generally, a political cartoonist is the proverbial kid who points out that the emperor has no clothes. Political cartoons transfer information in an intuitive, subtle way. Cartoonists document history with exaggerated depictions of important people and the absurdity of the day. As comics historian CT Lim writes, “They are caricaturists who hold up the savage mirror, satirizing the follies of political leaders and their policies with the aim of keeping policies straight and honest.” They insinuate, comment, criticize, and judge, often in the pages of newspapers with readerships in the hundred thousands. A good cartoon gets under the skin of its target, making them or what they believe in look ridiculous. But political cartoonists are a rare breed in Singapore.

It used to be that if a would-be political cartoonist wanted an audience, they’d have to take their work to a newspaper. There, if you drew something too critical or divisive, your editor would simply decline to publish (and pay for) it. To stay employed, then, you learned to draw well within the lines. Cherian George, now a media studies professor, was the art and photo editor at the Straits Times in the mid-nineties. “I supervised that line,” he said of the paper’s “better-to-be-safe-than-sorry” editorial stance. He knew implicitly which subjects were off-limits, and didn’t question it. “… I took it for granted. Singapore newspapers are not allowed to caricature our leaders. So be it. We’ll just work around it.”

Editors used to err on the side of caution, down to the letter. When Cheah Sinann, a Malaysia-born cartoonist, came to work for the Straits Times in the late 1980s, an editor voiced concern that his strip, The House of Lee, would be misconstrued as a commentary on PM Lee. Cheah was confused; he had based the strip on an eccentric neighbor in Malaysia. (“I didn’t know what all the fuss was about,” he said.) But he changed “Lee” to “Lim” and the strip ran for eight years.

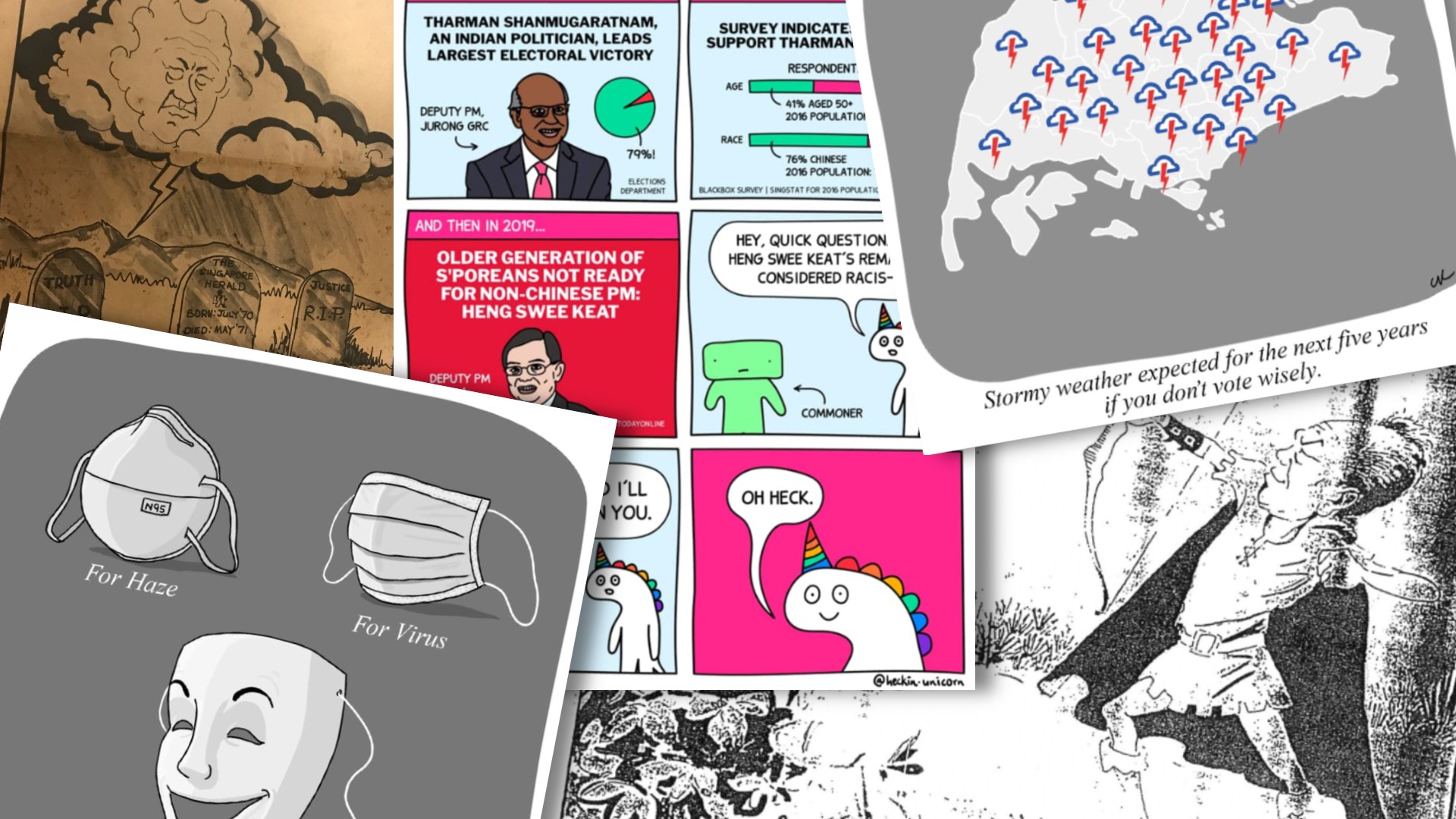

When your livelihood depends on a newspaper publishing your art, there are a few different compromises you can make. You can leave Singapore, like Morgan Chua did when the government yanked the Singapore Herald’s publishing license in 1971 (due to Chua’s pointed caricatures and illustrated criticism, legend says). You can hit the brakes on political criticism, and turn to light-hearted gag cartoons, like Tan Huay Peng and Sam Liew did at the Straits Times in the 1950s and 1980s, respectively. You can continue to draw stinging political content, but focus your lens on every country except Singapore, as Heng Kim Song does for Lianhe Zaobao. You can riff off the subjects that your editors give you to draw about, like Dengcoy Miel told CT Lim he does at the Straits Times.

Or you can bypass the papers entirely, and use Instagram and Facebook as a platform for your art. The internet, that great equalizer, has radically altered who gets to produce content for the masses. If you have a funny thought or a dissenting opinion, it could potentially reach millions of people within hours, regardless of your financial or social standing. No one will tell you what you can’t publish — at least, not until after the fact.

As a result, cartoonists like Guay Chong Kian, who draws the online comic SemiSerious, are always conscious of straying too close to the line. “If people get too offended, I don’t think it’s a good thing… I would still try to push the envelope a little bit, to make sure that it can be a little edgy,” he said, “but you can still maneuver it so that you’re still within the boundaries!”

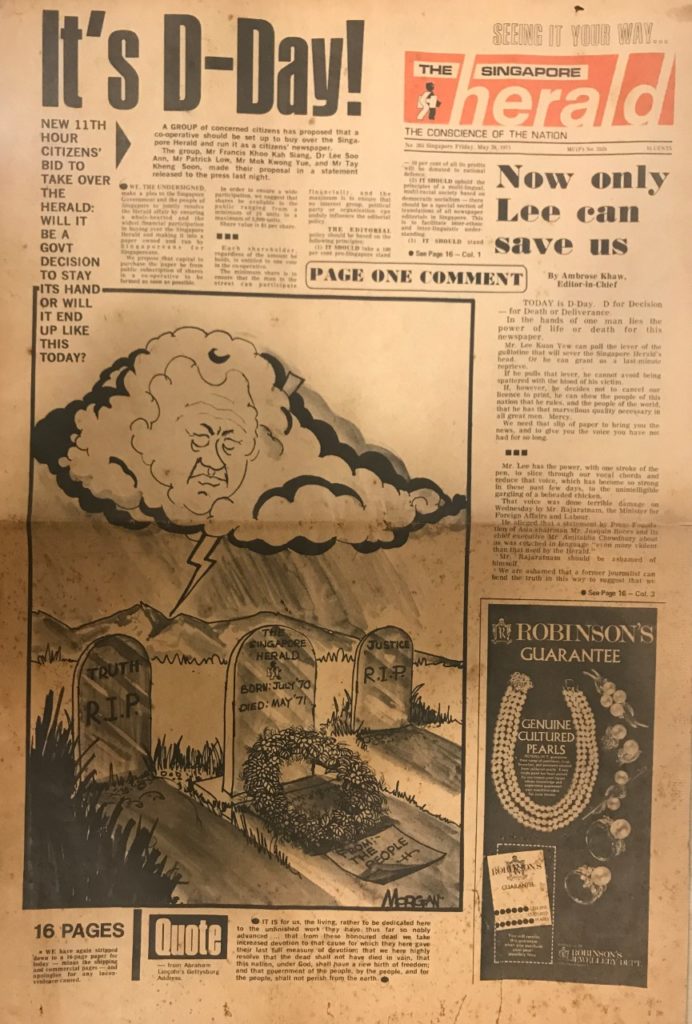

These “boundaries” are sometimes called OB markers, short for “out of bounds markers,” and refer to the murky boundaries of which local political topics are acceptable to discuss publicly. Though he believes poking fun at Singaporeans or even general Singaporean politics is fine, Guay personally defines what lies outside his own OB marker as attacks on individual politicians. “[Getting] too personal, naming or slamming somebody, it’s a little too in-your-face for me.”

Perhaps because of his status as an award-winning and internationally-recognized cartoonist, Sonny Liew is one of the few artists in Singapore who feels comfortable openly mocking specific politicians. The author of The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye has recently drawn cartoons lampooning Jamus Lim’s attempt to control the “PAP-lite” Workers’ Party narrative and the Ivan Lim scandal. His caricatures are no less incisive. In Charlie Chan, he drew “Mr Hairily” (a stand-in for PM Lee Kuan Yew), the despotic boss of a stationery supply company, with deeply furrowed brows and bared teeth. During the election period, an unnerving portrait of Heng Swee Keat, Sylvia Lim being bullied by PAP members, and an older caricature of K. Shanmugam standing with an attack dog were all posted by Liew to his Facebook.

Liew has been (sometimes famously) dancing around these markers since the beginning of his career in 1995. When he brought his first strip, Frankie and Poo, to The New Paper in as a second-year college student, he knew next to nothing about lettering, and — due to fears about legibility — the paper used a type font to replace Frankie and Poo’s hand-written text before publication. Sometimes, Liew would open that day’s edition to see that, at some point in the process, his words had been tactfully tweaked.

He’s learned since to balance raw passion with careful research. “There’s room for interpretation. There’s room for expressing opinions,” he said. “Even though it’s a very gray area. The key, for me, is to be responsible and accurate in speaking out.”

Liew has a fairly complicated relationship with the government; they’ve denied him funding to travel to literary festivals in Angouleme and Penang, but the National Arts Council, or NAC, congratulated him when The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye won the Lit Prize, and he enjoys a government-subsidized workspace at the Goodman Arts Centre. What the authorities have made clear in his case, Liew explained a virtual discussion hosted by the Substation, is that they separate the art from the artist. “It sounds like a strange distinction,” he added, “especially as my career is so intertwined with the book.”

Cherian George sees the withdrawal of the NAC grant after Charlie Chan’s publishing as a message, a symbolic stance that makes the government’s position more clear. This, in turn, regulates what artists feel like they have the liberty to say. “Artists can’t possibly predict if their work is going to be a major international bestseller and win awards…” he said. “The signal sent to all artists in Singapore is that your public funding is going to be at risk if your content criticizes the Singapore government. It’s a clear, explicit signal. So of course that’s going to factor into the choices that artists make.”

That said, “Things in Singapore are not as bad as in other countries. We don’t get jailed or executed or tortured,” for drawing comics, Sonny Liew said at the Substation, where he was in dialogue with Cherian George. The pair have been working on an upcoming book about the censorship of political cartoons, called Red Lines, interviewing cartoonists around the world for the last two years.

For all the relative freedom that a political cartoonist critical of Singapore enjoys on the Internet, its egalitarian nature means a great artist can easily get lost in a massive grab-bag of content, with quality varying wildly. CT Lim believes that generally the levelled playing field of the internet is a good thing, but, as a historian, tries to keep its drawbacks in perspective. “I’m sure there are many cartoonists out there [who are] very talented,” he said. “I don’t know all of them. And I have no way to find them because… there’s just way too much out there.”

A reader’s inability to consume anything but a fraction of a fraction of internet content might be one of the reasons that authorities, for the most part, let artists have their say. “In this age, it doesn’t quite make sense to ban things,” George said. “You’re only giving it free publicity. It will spread virally through social media. Ignoring satirical content that insults you is probably a government’s best option in many cases, because people have short attention spans anyway. That offending cartoon is just a drop in the ocean.”

Though an artist posting political content can amass a large following, every online cartoonist sits behind their screen, very much physically isolated from both their fans and each other. “In societies that are more repressive [than Singapore], artists and writers get a lot of their reward from the intangible benefit of being part of a larger community — who are in this together,” Cherian George said. “For a long time, Singapore has just lacked that. Anyone who tries to be a critical artist is very much alone.”

A few years back, Sonny Liew and a few friends tried to set up a society for comics artists and cartoonists. The idea was to model it after groups in New York, which held idea-swaps and meet-up-and-draw pub crawls. “It just never worked, because there were too few of us to sustain this thing,” Liew said. “In New York, you’d have a large critical mass of comics creators. So, every week, if only a small percent of that turns up, you’d be okay. In Singapore, if two people drop out, you had, like, no one else left to meet up.”

Why aren’t there more political cartoonists in Singapore? Maybe it’s because things aren’t so bad. It can’t be censorship alone that explains the absence of editorial cartooning. Because that wouldn’t explain why there’s so much good cartooning in far more repressive societies,” George said. “I suspect Singapore’s authorities have hit a sweet spot where it’s repressive enough to discourage critical work, but also rewarding enough such that people feel they have too much to lose and are therefore unwilling to take even small risks. Whereas in many more repressive societies that are also much less comfortable, there’s much more risk-taking. Artists and writers are willing to pay the possible price.”

Other stories:

Everything old is new again: Singapore’s long history with blackface

The insidious problem of casual sexism and why I called out Okletsgo

Loving outside the lines, Singapore’s interracial couples break down racism and division