This year’s Singapore Biennale is a sprawling, four-month-long exhibition showing the work of artists from across the globe in 11 venues scattered across the Lion City.

The immersive art experience kicked off a few weeks ago, and runs until March, but despite it taking place in the Little Red Dot, the Philippines is front and center in more ways than one: not only are five Filipino artists showing their works in the biennale, but the entire event itself is being helmed by Filipino artistic director Patrick Flores.

Is the biennale something that only the turtleneck-and-beret-clad art snob class are likely to appreciate? No. Or at least, not if Flores has his way.

A professor of art studies at the University of the Philippines (UP) with a background in art history, and a curator at the UP Vargas Museum, Flores has been entrenched in the art scene for over two decades. He also led the successful comeback of the Philippines at the 2015 Venice Biennale after a 51-year absence from the art festival.

Flores has titled this year’s Singapore Biennale “Every Step in the Right Direction,” a reference to Filipina revolutionary Salud Algabre, a seamstress whose 1930s peasant movement against American colonialism ended in the death of many of her comrades. In response to criticism that her movement was a failure, Algabre is said to have replied, “No uprising fails. Each one is a step in the right direction.”

“Every step is a risk, a responsibility, and a position,” Flores told Coconuts Manila in an email. He added that “what it means to fail and what it means to succeed are re-conceptualized” in the Singapore Biennale.

“The biennale thinks through the difficult times the world faces at the moment,” Flores said, adding that the free, multi-event art exhibition is a means for the public to “recover joy and thoughtfulness,” though such a vision is no easy feat given it requires both a sense of delicacy and urgency.

“I wish for a thoughtful biennale, if not an intricate one that does not give in to [the art] spectacle and does not try too hard to be different,” Flores reiterated. “It honors humble, humbling gestures of change.”

Flores recently spoke to Coconuts Manila in depth about what sets this year’s biennale apart — and what to expect from the Filipino artists being exhibited there. (The following interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.)

You’ve curated and directed a number of art shows in the past. How is the Singapore Biennale different, or the same?

This is my first time to be an artistic director of the biennale. It’s very different from being a curator. I was trained as an art historian and my curatorial work has extended from that discipline. So this is a bit of leap for me, one that was productive and rewarding because I was able to bring together the sources of intelligence which have shaped me: art history, curation, and contemporary art.

So it’s more dynamic?

The biennale is a complex organism with so many moving parts. The curatorial part is only one of them. There are others, like public interface, relationship with the cultural bureaucracy in Singapore, and the effort on my part to propose a different methodology of biennale-making. The “biennale” as a structure becomes part of the investigation, the creative research, enfolded into both art history and the region.

I hope to impact curatorial methods, renew attentiveness to Southeast Asia as a region, and broaden our perspectives through which we view this region to include ways of seeing it other than through colonialism. I want to offer instead a geo-poetics and re-map the world through art. This is one way to rectify, as it were, the distortions of colonialism and globalization. An interesting challenge has been one of space and how to integrate the breadth of venues and sites involved with the conceptual impulse. As a result, I hope that in this biennale, Singaporeans and visitors [from outside the country] alike will explore and renew their experience with Singapore by walking, getting lost, [and] finding places.

Have you previously worked with the Filipino artists participating in this year’s biennale? What excites you about this particular selection of Filipino artists?

Yes, I have worked with them in one way or another. I am drawn to their sensitivity to [the] material as well as their sympathy to the world around them. They don’t let convenient discourses reduce their art to illustrations or instruments. I like the performativity that inheres in their thinking and their doing.

What makes Filipino art unique from Singapore or the rest of Asia?

Its distinction comes from different sources: history, milieu, society. But aside from this, let us consider, too, biography, the process of learning, political intuition, and migration. It’s hard to pin down uniqueness without drifting towards some kind of easily recognizable signature. I avoid this because this is a template for capture. I prefer to look at Filipino art as a moving constellation that mutates every time it comes in contact with other constellations. Surely, there is some kind of root or core. But even then, this root or core varies from artist to artist and the conception of what is “Philippine” or “Filipino,” or what is the right kind of art for the time. It’s an ethical and aesthetic category, this thing called Philippine/Filipino art.

You also served as curator for the Gwangju Biennale sometime back. In contrast, the Manila Biennale was launched just last year. Does it surprise you that we’re a little behind in that aspect given the city or the country’s rich art scene?

I don’t think we need to look at things in terms of being behind or being ahead, or being punctual or tardy. All these pertain to time, and time itself is a problem to be grappled within the discourse of the contemporary. I tend to believe that there are no latecomers in the contemporary. We instead gesture towards different, interpenetrating modalities of time and place. These gestures should prompt us to think through the sort of platform we think we need to create conditions for contemporary culture to thrive creatively and critically.

Do you have a broader vision for a followup, or any ideas as to the direction the Manila Biennale, helmed by the late Carlos Celdran, may be headed in the coming years?

I was not part of the Manila Biennale. But in a forum where I spoke with Carlos Celdran, Carlos thought of the biennale as being an open system, one that could be handed over horizontally from peer to peer. It’s a promising model if carefully plotted out.

You also led the Philippines’ return to the Venice Biennale back in 2016, which was a pretty big thing after our 51-year absence. How did that feel, and any interesting stories behind it?

I enjoyed that experience because I was able to complicate the idea of the Pavilion and the Philippine at the same time. For me, curating the Philippine Pavilion was productive; it was an opportunity, not an occasion to merely take the national and the biennale to task, or to extol it uncritically. I talked about Genghis Khan, the South China Sea, Philippine modernism. To reduce these to nation or the biennale is to lose sight of a more copious “Philippine,” not the nation-state of the Philippines, but the Philippine as a procedure of making worlds.

What do you think the Filipino attitude is towards viewing and consuming art? Are we more relaxed about it now, or is it still something that the public might think is only reserved for “people in the art world?”

The general public can relate to both contemporary art and art history when these are made to speak to the concerns of a living culture. It is also important for the artworks to be made accessible through a range of programs — from talks and workshops to educational engagements with schools. People now respond to art in many ways. There are, in other words, many entry points, and not all art is produced in the traditional centers of art-making in the West, nor is it only made accessible in the traditional structures of institutions.

“Every Step in the Right Direction,” therefore, becomes an invitation as well as an inspiration for us to decide on which steps to take towards what we believe is the right direction. As we pursue this project to make a difference in a troubled world, we abide by both the patience and the risk to take action with others for the rightful claim to both art and place. This is why apart from the exhibitions, the biennale collaborates with initiatives on the ground that have endeavored over the years to form an active public sphere in which heritage, moving image, and performance prove to be central.

On a personal note, are you still based in Manila? And do you still curate for the UP Vargas Museum? What other projects do you have in the works?

Yes, always been based in Manila, never studied or worked abroad. I still teach art history in UP and curate the Vargas Museum. This December, we open at the Vargas an exhibition of five young curators. This is a wonderful chance for them to practice curation. I am also directing the Philippine Contemporary Art Network, and we have lined up publication projects on criticism.

Finally, can you expound on how the title “Every Step in The Right Direction” is inspired by Singapore artist Amanda Heng, and Filipino revolutionary Salud Algabre? And is it fair to say that feminism holds a prominent place in the Singapore Biennale because of that?

The line comes from Salud Algabre, a Filipino woman, a militant seamstress, involved in the peasant movement in the 1930s in the Philippines. The political action that this movement pursued was perceived to have failed. When a scholar years later hinted at this failure in an interview with Algabre, she would rectify the impression by saying that “No uprising fails. Each one is a step in the right direction.” On the whole, Algabre’s spirit substantially inspires because it works towards change in the present, and in the face of a past that guarantees a persistent, painstaking future… and lasting change may come only in diligent, incremental efforts and not in a singular stroke of the avant-garde.

The biennale’s title also echoes Amanda Heng’s work Let’s Walk. We seek to draw attention to what may be overlooked, in the case of the everyday step and the act of walking, a simple and ordinary movement. In Amanda’s work, walking also takes on a different dimension in promoting deliberation and sharing, connecting with pasts and each other, which the biennale’s proposition embodies. She will stage a new edition of and elaborate on her renowned Let’s Walk series, which speaks directly to the title of the 2019 edition.

Salud Algabre and Amanda Heng who come from different historical climates and cultural genealogies, [are] brought together in the event in Singapore as contemporaries, as they propose a feminist poetics and politics that will hopefully enliven the imagination of what it means to be political in the decision to do what is right in our everyday waking and walking life… Yes, they hold a prominent place in the Biennale. [It’s] about time I think that a leviathan, hegemonic platform like the biennale is leavened by the promise of women taking steps in the right direction.

BONUS PRIMER

Patrick Flores offers a rundown of the Filipino artists being shown at the Singapore Biennale:

Miljohn Ruperto presents “Geomancies,” comprising a film, a series of photographic and video works, and a performance piece.

Lani Maestro presents an installation consisting of a structure that holds over a hundred pieces of capiz (windowpane oyster) shells.

Alfonso Ossorio’s “Congregations” is a class of works that swarms with ornament, fantastic objects from driftwood to rhinestone, and glimpses of otherworldly references, akin to dreams or triggered by a heady imagination.

Gary Ross Pastrana explores the stages of transformations in a work that intersects both theater and the exhibition space, where objects transform from props to sculpture and back again.

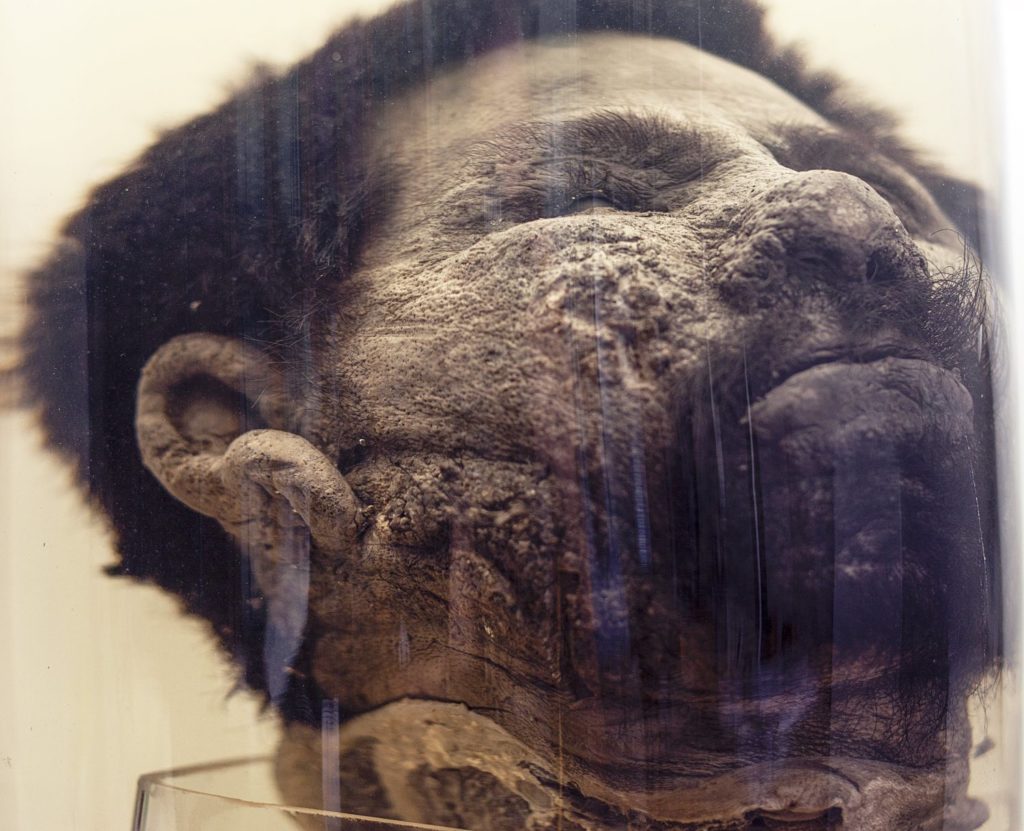

And finally, Mark Sanchez deals with the accumulation, classification, and inventory of images and information in his practice. His new commission concentrates on the figure of a peasant leader superimposed onto a diagram by [Mamitua] Saber. “The Mamitua Saber Project” takes off from the work of Dr. Mamitua Saber (1921–1992). A sociologist, institution-builder, cultural worker and educator, Saber was instrumental in developing Mindanao’s cultural and civic life.

Read more arts and culture coverage from Coconuts Manila here.

Reader Interactions