As dawn breaks over Yangon’s Passport Issuing Office, a throng of would-be globetrotters gathers in front of the squat Yankin Township building and snakes around the corner. Family members take turns holding spots in the queue while others nap in their cars. Parents buy snacks for restless children from the vendors lining the block. With the promise of a well-earned holiday or a better life abroad in the air, a few hours of waiting and a K30,000 (US$22.50) fee are a small price to pay for the more than 2,000 people who flock to the office every day.

But what few of these aspiring travelers realize is that the convenience of buying or renewing a Myanmar passport is a privilege afforded primarily to Burmese Buddhists. For Muslims, people of Chinese descent, and other categories of scorned citizens, the dream of international travel comes true only for those willing to endure a racist nightmare.

Over the course of this year, Coconuts has spoken with half a dozen passport applicants who have described a system of racial discrimination at the Passport Issuing Office that has flourished even since the process was reformed under Myanmar’s previous government in 2013.

That year, the government under then-President Thein Sein cut the waiting time for passport issuances from 21 days to 10 days, lowered fees, and removed several tedious steps from the application process. However, for applicants who are not ethnically Bamar and religiously Buddhist, the process contains just as many hurdles as it always has, and as nationalist sentiments have risen since the parliamentary sweep of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and her colleagues in the National League for Democracy in 2015, more applicants are reporting that the hurdles have multiplied.

The most blatant manifestation of this ethno-religious inequality, as well as the earliest in the process, is the existence of an unmarked queue that is reserved for people considered to have “mixed blood.”

The nameless queue

“When I got to the passport office, I saw this really long queue, and I thought, something is going on here,” said Jude, a Yangon resident who applied to renew his Myanmar passport in February. “When I approached the officer at the entrance for directions, he sent me to the line for people with mixed blood (thway hnaw). In this queue were people with [valid national registration] cards, but their races were mixed – Indian mostly, but also Chinese and other people. They all had to queue in this place.”

The “mixed-blood” queue is unquestionably the worst queue in the building. Although Bamar Buddhists probably make up a majority of the applicants on any given day, they are given their pick of 11 lines that each lead to a window where they can present their application documents to an immigration officer. “Mixed-blood” applicants are confined to a single line.

“Maybe they are moving like 10 feet an hour, while we are moving like two feet an hour,” said Kyaw Moe Tun, executive director of Yangon’s Parami Institute of Arts and Sciences. He spent a total of six hours in the “mixed-blood” queue on May 15 because his national registration card indicates Chinese heritage. He documented the experience in a series of semi-viral Facebook posts that prompted numerous commenters to describe identical experiences.

The “mixed-blood” queue is further described in a report released today by the Burma Human Rights Network (BHRN). The report quotes one applicant who explains why the segregation policy at the passport office has received almost no coverage over the years.

“There is no official announcement about discrimination against the ‘mixed blood’ people, and there are no [written] instructions available at the office, so I feel that we are being discriminated [against] discreetly,” applicant Yin Phyu Theint told BHRN.

Officers outside the passport office declined to speak to Coconuts for this story. However, the existence of the segregated queue was confirmed by an “agent” who expedites passport applications for a fee using her personal connections. She spoke on condition of anonymity, saying: “If you are not Bamar-Buddhist, they are going to ask you questions and check your documentation and background. Sometimes it takes longer, and they have to crosscheck with the immigration officials to see that everything is correct.”

Several applicants corroborated this assessment, describing further instances of racist treatment that came after having to wait in the snail-paced procession.

“Next, we had to go into this little room where they pretty much interrogate us for three to five minutes. Some people got longer,” said CW, an applicant of Kokant descent who asked that her name not be used. “It’s like a little box room where there’s an officer behind the desk, and they let people in one by one without any explanation. And then, you may or may not get your passport.”

BHRN has identified one officer who has conducted these interrogations as Tin Aung Cho (Staff Number: LaWaKa-5799).

CW spent five hours at the passport office that day in February and left before completing the process because she had to go back to work. However, had she completed the process, she probably would have been subjected to the next hurdle: extortion. While applicants of all religions and ethnicities are pressured to pay bribes at the passport office, the pressure is especially pronounced for those deemed to have “mixed blood.”

Than Toe Aung, a Yangon-based activist who has previously exposed anti-Muslim violence at the hands of city authorities, described to Coconuts his experience with the immigration officer behind the desk.

“We see your grandfather was Indian,” the officer reportedly told the activist. “It may be difficult for you to get a passport. Maybe if you paid some respect money, we could make it happen.”

READ: Arrest, abuse, cover up: A Muslim poet’s harrowing encounter with Yangon police

Than Toe Aung resisted, and the officer backed down, not wanting to call attention to the scheme. However, those who do not call the officer’s bluff are often forced to pay huge bribes. For example, Jude, the applicant mentioned above, said he ended up paying a total of K340,000 (US$255) in bribes over the course of several months to avoid more delays on top of the ones he had already suffered.

Jude reflected: “Being a minority in this country … it hurts. For two or three days, I couldn’t work. I’m a good citizen. I’ve been paying taxes since I was 20 years old. I was born in this country. It’s like paying extra money for being a certain kind of person.”

He added: “It’s like requiring Jews to go in a different line.”

Being ‘Bengali’

The term “mixed blood” dates back to 1989, when the ruling State Law and Order Restoration Council began updating the national identification system. Muslim citizens whose national registration cards were updated often found that the term “Bengali” had been added to their ethnicity sections, on top of whatever ethnicities they had claimed themselves. The term “mixed blood” arose as the colloquial version of the official term; both imply that Muslims in Myanmar are at least partially foreign.

Under Myanmar’s constitution, people of all ethnicities are guaranteed equal treatment under the law. Nonetheless, anyone whom the passport office staff deem to have “mixed blood” – Muslim or not – can be subjected to the unwritten segregation policy, and those whose ID cards contain the term “Bengali” suffer its harshest iterations.

According to BHRN, even after they pay bribes, their application forms are stamped with the Burmese equivalent of the letter “B.” Applicants with beards are checked against photos of wanted criminals that are hung from the wall of the office. And while their passports are being processed, Special Branch (SB) agents are dispatched to their neighborhoods to interrogate their neighbors and verify their personal information.

An applicant named Zaw Win told BHRN: “One SB officer and ward administrator came to my home, but at that time, I was not at home, so they checked the guest list and asked for my citizenship card. The next day, I was called to the SB office and asked to produce my national registration card, family registration card, and guest list, and I had to give them copies of these documents.”

Even though Zaw Win was able to produce the necessary documents, having SB agents come looking for him had already left a mark on his reputation.

“It was not good for me. People looked at me with suspicious eyes,” he said.

Moreover, in the eyes of the officers at the Passport Issuing Office, Bengali ethnicity is a disease that infects an entire family, transcending even the flawed understanding of genetics that places other applicants in the “mixed-blood” category in the first place.

TK, a Muslim doctor who asked that her real name not be used, told Coconuts about the experience of her sister’s father-in-law, who applied for a passport in March so that he could perform the Hajj – an obligatory visit to Mecca – before he dies. The officials told him that his passport could not be issued immediately because one of his other relatives by marriage has “Bengali” written on her national registration card. When he tried to offer a bribe, the officials refused it, instructing him instead to come back to the office to check on his application’s status in a month’s time. When he came back, he was told to come back again after another month. The next month, he was told the same thing. His next appointment is at the end of June.

“It’s a weird thing. Just because his sister-in-law is Bengali, this old man, who is 83 years old, a pensioner, and has worked for the government for more than 40 years – he’s considered ‘mixed blood,’” TK told Coconuts. “People with a religion other than Buddhist are facing a lot of difficulties living in this country.”

She added: “We sometimes joke: If you had to go to hell or the passport office, where would you choose to go? People with ‘mixed blood’ will always say: ‘I would rather go to hell.’”

Additional reporting by Nay Paing and Aye Min Thant.

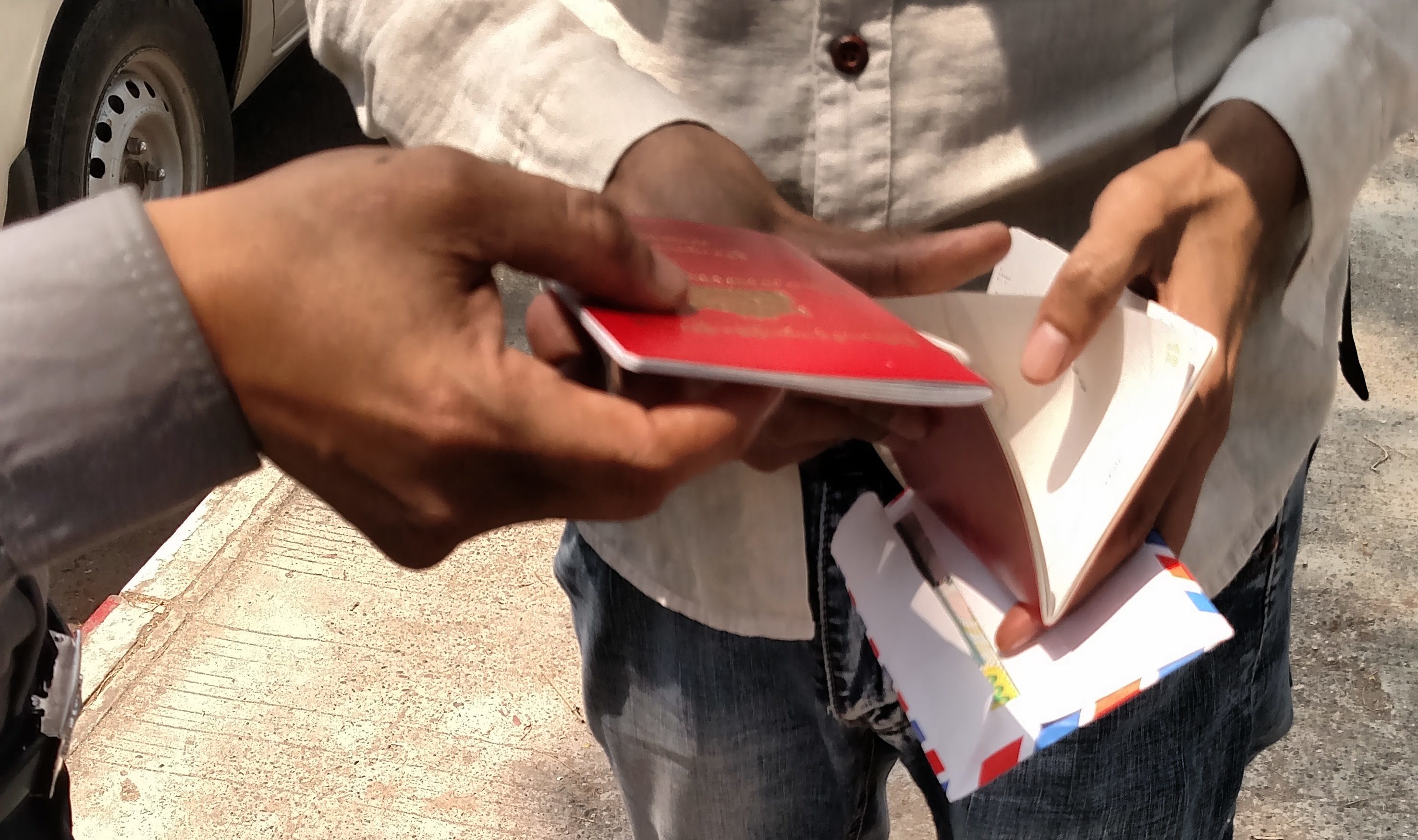

TOP PHOTO: Applicants wait to enter Yangon’s Passport Issuing Office on May 21, 2018. (Photo: Jacob Goldberg)

Reader Interactions