Singaporean elitism is a rather touchy subject, but it’s a much-needed discussion. This guide to the GCE O-Level Social Studies subject for Secondary 3 students had some, er, questionably classist content that brought that discussion to the foreground of social media once again.

In a book found by Ahmad Matin, a former teacher at Ahmad Ibrahim Secondary School, the guidebook that boasted “comprehensive revision notes” and “effective strategies” held a controversial section that outrightly divided Singaporeans by their Socio-Economic Status (SES).

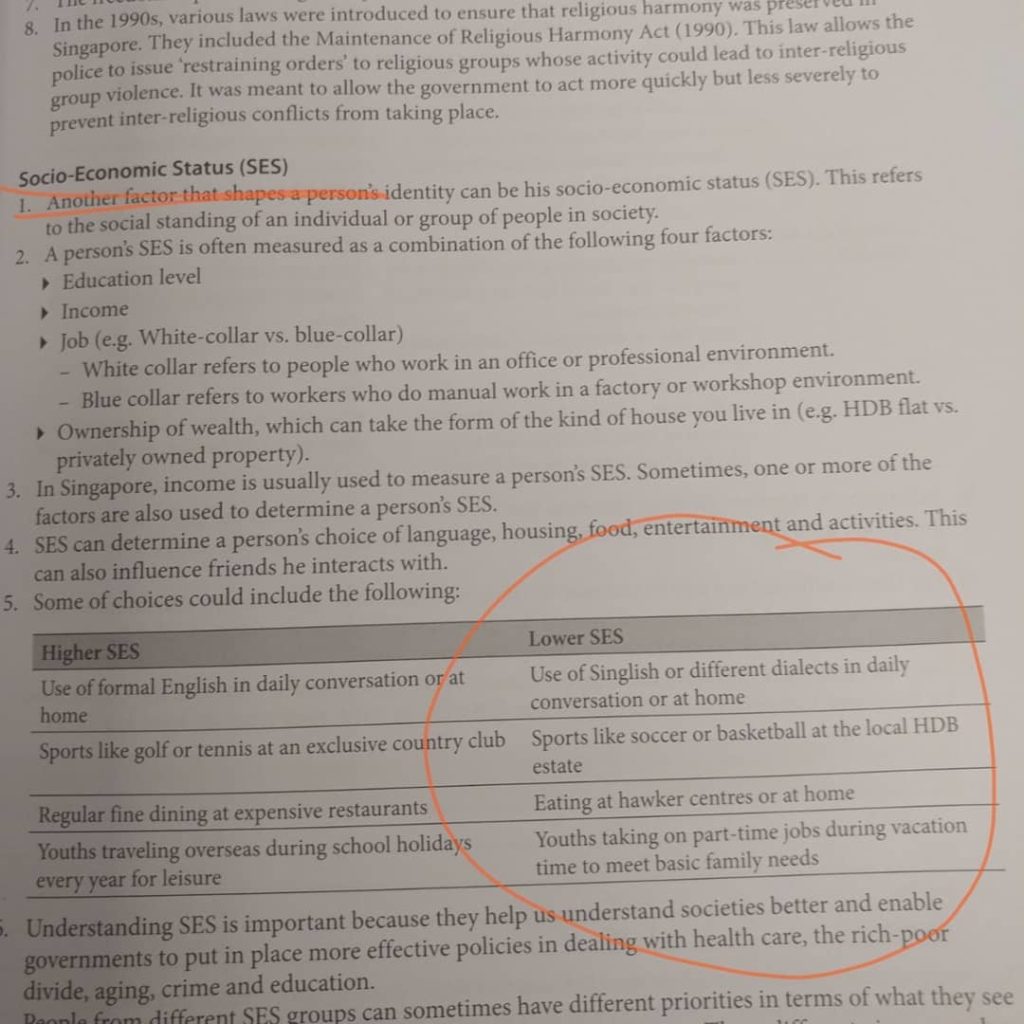

“Understanding SES is important because they help us understand societies better and enable governments to put in place more effective policies in dealing with health care, the rich-poor divide, aging, crime and education,” wrote the book’s author, Rowan Luc.

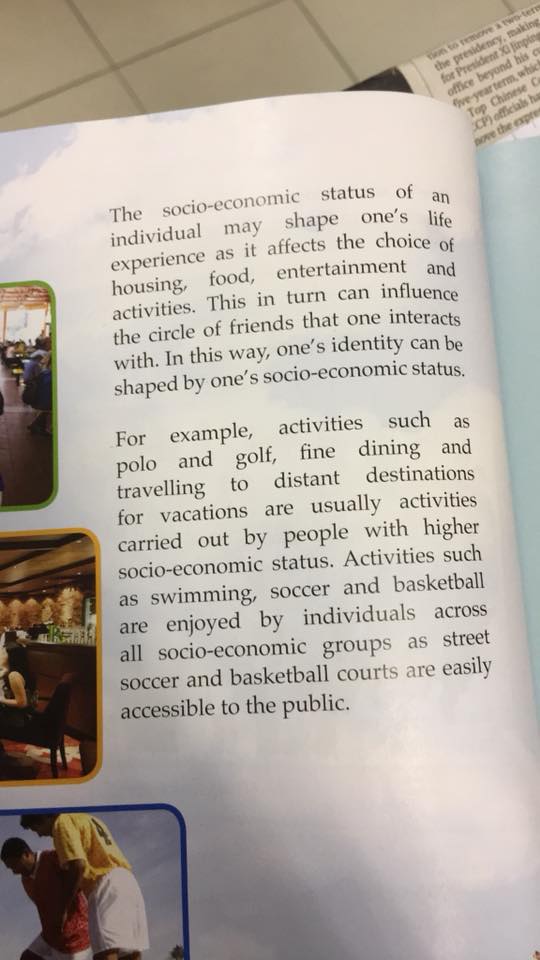

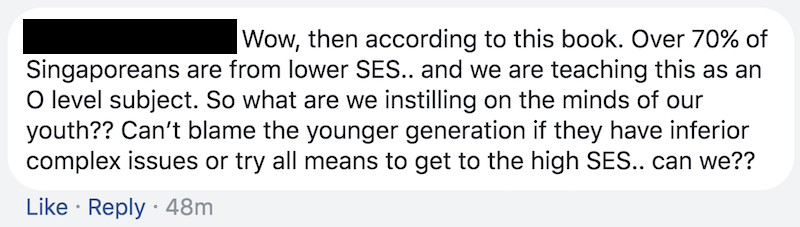

Sure, household incomes, wealth, and education levels play a huge part in the categorization of social classes, but Luc might be oversimplifying things. Singapore’s society can be pigeonholed into Higher SES and Lower SES, he wrote. So according to the activities of each group, a high degree of locals fit the distinction of being lower class.

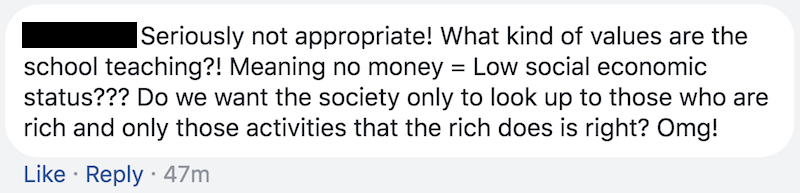

Angry reacts only

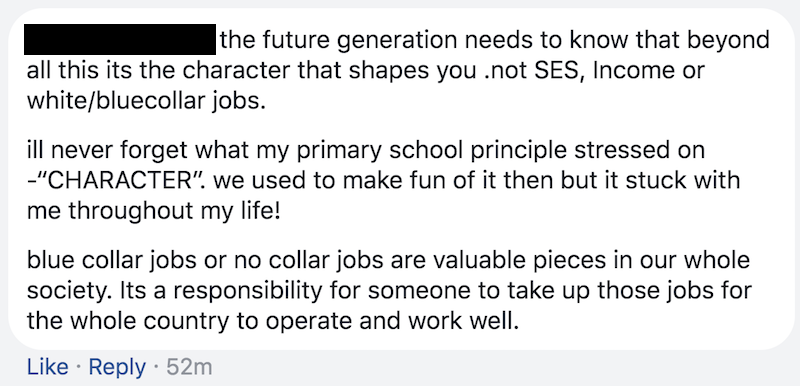

Many called bullshit on the book because you can’t just split society into two, and teaching such an elitist binary system to young students is pretty misguided. Finer reading of the text, however, notes that SES is actually measured by one’s income (and other factors), and that SES can determine the one’s lifestyle choices, like making decisions to eat at hawker centres or expensive restaurants.

The table could have been clearly labeled to define priorities then, instead of using the terms “Higher” and “Lower”. Other parts of the guidebook point to a more rational explanation of SES.

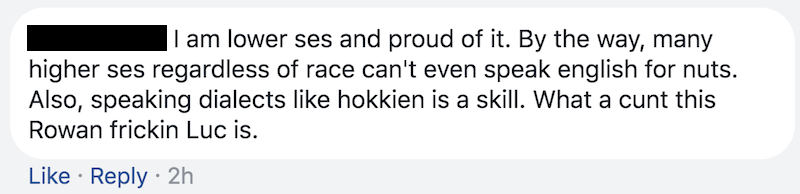

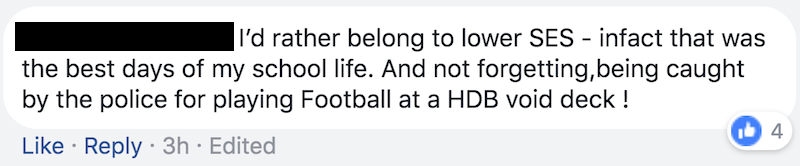

But most, especially students, could glance over the finer print and jump straight to table, which is understandably infuriating if taken out of context. Lots of folks are just mad that their daily life is classified as lower SES, which can be misinterpreted as being lower class.

Others pointed out that it’s not an official school textbook, and that Ministry of Education (MOE) has nothing to do with the assessment book — approved commercial learning materials must bear the MOE stamp of approval. This was soon confirmed by MOE.