We don’t typically measure how much we enjoy a meal by counting points in authenticity, but with certain cuisines in Singapore — like Sichuan food — restaurants use the authenticity element as a key selling point, so alas, Chengdu Restaurant … let’s dance!

If you work around Chinatown or Telok Ayer, then you’ve likely spotted Chengdu Restaurant before. It opened in the spring of 2018, around the corner from Amoy Street Food Centre, alongside dozens of trendy restaurants and bars in the area. Inside, on the first floor of its shophouse space, Chengdu Restaurant keeps up contemporary appearances: A cluster of red paper umbrellas, angled upside down, acts as lampshades for the ceiling lights. We’d sum up the rest of the decor and furnishing as “Muji meets Ming dynasty.”

Beyond the looks, though — the feel of the place is the stuff of every Chinese kid’s upbringing: a room full of people talking over each other, mostly in Mandarin, punctured by the discordant clang of ceramic dinnerware and utensils hitting and scraping against each other. Dining tables set unapologetically close together so as to maximize use of space. Speedy, no-nonsense service.

Authentic, so far? Yes, actually.

Here are yet more authenticity points for you: One of the co-owners of the restaurant, Stella Wang, was born and raised in Chengdu, and the two chefs managing the menu and the kitchen — head chef Qing Jun and chef Jing Xiao — are also from Sichuan province, where they worked in F&B for many years before coming to Singapore.

Now let’s get to those new dishes.

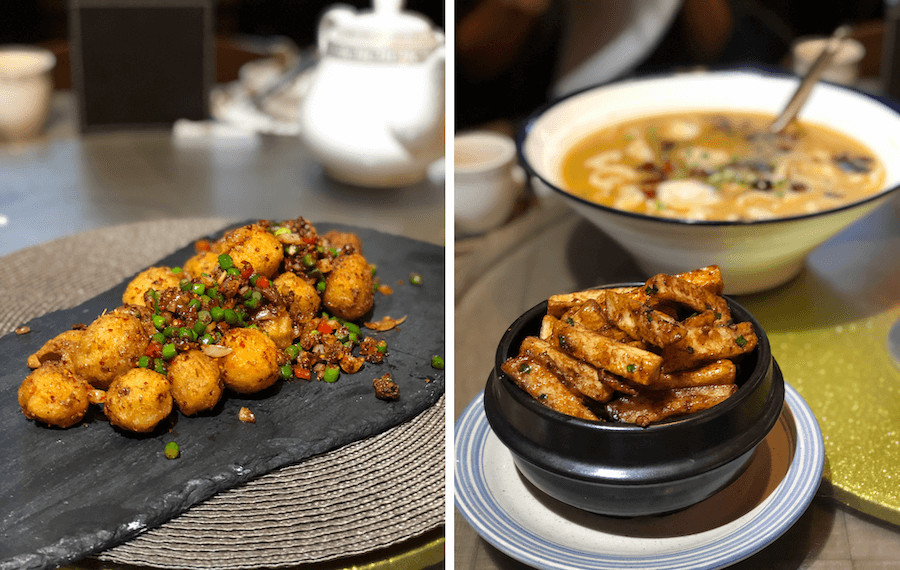

The first thing we — Coconuts Singapore, elbow-to-elbow with other reps from across Singapore’s mediasphere — try is the Beggar Potatoes ($12.80), spherical cuts of potato that have been parboiled, flash-fried, then stir-fried along with a mixture of minced onions, crushed dried chili, cumin powder and chopped garlic scapes. Garlic scapes are the long, green stems that flower out of a garlic bulb. Some farmers cut these stems off to yield larger bulbs, but in China, they’re usually given time to grow out into long stalks, and used as umami-rich greens. They’ve got a pleasantly light crunch on the outside and a plump, juicy interior that carries sweet garlicky notes.

Back to the potatoes. Thanks to its shape, each piece of potato gets thoroughly, uniformly flavored across its entire surface, and yields the perfect ratio of soft, fluffy potato center to its piquant outer layer — and it’s especially good if you pair each bite with that stir-fried topping of spicy, cumin-y garlic scapes.

When a large bowl of Fish Fillet in Sour Soup (small $22.80, large $29.80) arrives at our table, however, those authenticity alarms start ringing. Suan cai yu, as the dish is called in Chinese, is one of the most well-known and widely liked dishes from Sichuan province. Chengdu Restaurant’s is notably lighter in flavor than versions we’ve had elsewhere, mostly because they’ve significantly dialed down on the suan (sour) element that comes from pickled mustard greens (suan cai).

Despite this tweak, it’s still a tasty take on the traditional — just think of it as a lighter, homemade version of suan cai yu whose broth is clear enough to drink. The boneless sole fish fillet pieces swim in a savory broth spiked with ginger, Sichuan peppercorns and suan cai. The fish is flavorful and tender, and there’s lots of it — but please don’t neglect the suan cai and enoki mushrooms floating alongside it. They’re great when paired with the mildly sweet sole, or ladled on top of white rice.

Then, there’s the lightly soy-glazed Roasted Foie Gras ($42.80) paired with slices of king oyster mushrooms. We get that there’s a target clientele that would happily order such a dish (it comes presented on a bed of dry ice to add a layer of visual grandiosity) — but we’re not it.

The way they’ve cooked the foie yields a texture with too much bite (“al dente” comes to mind), but we’re more into the rich, buttery, melty texture achieved through pan-searing, or the silky-smooth variety from a terrine. There’s still a pleasant depth of flavor, but we’d think that your enjoyment (and potential diner’s remorse) over this dish depends on 1) what you like and expect in your foie gras, and 2) whether you have an expense account provided by a company or a parent.

The Sichuan Eggplant Claypot ($12.80), strips of eggplant that have been thickly coated in flour, deep fried, and flavored with a dusting of Sichuan spices, may be less highbrow, but are far more satisfying. Each piece retained an extremely gratifying crunch from top to bottom even when the dish had cooled past its window of peak eating time.

We also tried the Salt and Pepper Pork Ribs ($22.80), which are parboiled with ginger, flash fried, then flavored with crushed Sichuan peppercorns, cumin, chili powder, and — like the Beggar Potatoes — tossed with stir-fried onion mince and garlic scapes. It’s an intensely satisfying flavor combination, and people who tend to complain about fried foods being “too oily” will be glad to see that Chengdu Restaurant’s pork ribs are a much “cleaner” version of typical fried pork ribs. Plus, the ribs come with cartilage in every bite — great if you love the crunchy stuff as much as we do. If not, then just eat around the cartilage. The meat is tender and comes right off.

The Braised Beef Tendon with French Bean ($26.80), on the other hand, was tender in an unpleasant way. We love us some good “Heavens to Betsy, this is some silky-sexy-soft, melt-in-your-mouth tendon,” but this one was more on the level of a failed Jello shot: a bit uneven in texture, with an unpleasant gumminess to it in some parts. The soy-based braise had some token Sichuan spices and fresh chili pieces sprinkled in, but the end result was something lighter, and more lackluster, than we had anticipated.

Chengdu Restaurant’s greatest deviation from the authentic Sichuan food playbook, however, is the Sichuan-Style Spicy Pot ($28.80, pictured above in header image). In Chinese, it’s known as mao cai, essentially a mala stew with various cuts of meat and vegetables cooked in a mala sauce base with plenty of chili oil. Its flavor profile is pretty similar to that of mala hot pot, with the key difference being that all the ingredients arrive at the table already cooked, so that you don’t witness any of that live simmering action.

As the official Chengdu Restaurant presser says, it’s a “quintessential” dish of the region. The contents of the pot before us really reflected a more localized palate, though: There were large prawns, slices of luncheon meat and squid pieces inside. None of these are outlandish additions to a traditional bowl of mao cai, but the fact that they make up the majority of the dish’s contents is outside of the norm. Chengdu is a landlocked city that’s pretty far away from the ocean, so historically (and even to this day), locals would typically favor beef, pork, chicken or freshwater fish as their preferred sources of meat. None of these were in Chengdu Restaurant’s version of mao cai, which again, is a matter of preference.

There is, however, lots of tripe — both white and black — as well as quail eggs, black wood ear mushrooms, beansprouts and Chinese celery stalks. We also appreciated the inclusion of the wide, flat cellophane noodles made of sweet potato starch (fen tiao) that’s used in restaurants in Chengdu.

At its core, Chengdu Restaurant is authentic, in that the foundational flavors are all there and you are getting the essence of Sichuan cuisine. We recognize that we haven’t yet tried its core menu offerings, and can also appreciate that new dishes are the kitchen’s way of experimenting and going outside of its comfort zone. But, if you’re that person who goes into restaurants looking to flex your food knowledge, the one who will keep interrupting your dinner companions to point out — actually, in Chengdu, they do it like this — then perhaps these new menu offerings are not for you.

FIND IT:

Chengdu Restaurant is at 74 Amoy Street.

6221 9928. Mon-Sat 11am-3pm & 5-10:30pm, closed Sun

MRT: Telok Ayer