For author Simon Vincent, being a Singaporean in the 21st century involves a navigating a few paradoxes.

“There is a strange tension now,” Vincent, 28, told Coconuts Singapore in a recent interview. “We seem to know that we need alternative voices, but then we don’t seem to want to give them the space for that.”

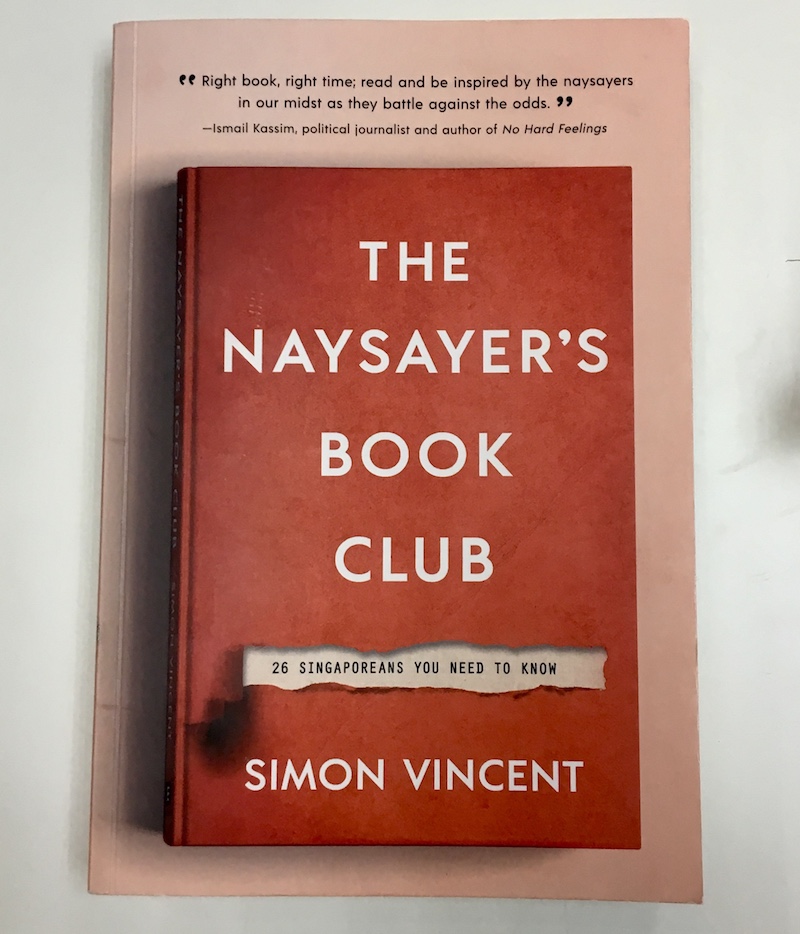

In his new book, The Naysayers Book Club: 26 Singaporeans you need to know, he introduces us to some of the Singaporean writers, artists, and thinkers who have made their homes inside that tension, and to the literature that inspires them.

Published by Epigram Books, the book is a look at the impact of Singapore’s legal restrictions on both the press and non-professional discourse. In 26 insightful profiles, Naysayers shines a spotlight on these people, whose names we may only know from the headlines.

The title, Vincent says, comes from academic and former diplomat Kishore Mahbubani’s now-famous exhortation for more naysayers, or people to question authority and contest the status quo for the benefit of the country.

“We need to create new formulas, which you can’t until you attack and challenge every sacred cow,” Mahbubani said while on a panel at Singapore Management University, The Straits Times reported last year. “Then you can succeed.”

But while politicians and civil servants publicly lauded the invitation for discussion and debating new ideas, many of the Singaporeans who heeded the call seemed to have encountered an icy welcome.

Freedom of expression, or the lack of

The Singaporean government’s relationship with the press offers a clue about the country’s self-identified lack of contrarian voices. The city-state currently ranks 151st out of the 180 countries in the World Press Freedom Index — behind Russia, Myanmar, and other nations where reporters have been jailed or assassinated for publishing the “wrong” story.

Here, however, control over the press is often exercised through a variety of constitutional means.

British author Alan Shadrake was arrested and jailed for a month in 2010 after publishing a book critical of Singapore’s death penalty, while Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong famously sued Singaporean blogger Roy Ngerng for defamation in 2014.

High-profile cases like these are not that common, but journalists and academics do report being dismissed from their jobs, blacklisted, and passed over for visa applications — allegedly in retaliation for publishing unsanctioned points of view or personally offending certain officials.

‘Being used by foreigners’

Many of Vincent’s subjects — from internationally celebrated artist Loo Zihan, to hyper-local activist Jennifer Teo — have been censored, harassed, or labeled anti-Singaporean for publicly expressing views that were out of step with the establishment.

Kirsten Han is one of the subjects profiled in the book. She is editor-in-chief of the online publication New Naratif, which publishes both news stories and scholarly articles from around Southeast Asia. In Han’s view, even the term “naysayer” suggests that in some way, the culture sees public discourse in very black and white terms.

“It just so happens that the Singaporean context makes advocating for something such a sensitive issue that it becomes ‘naysaying’,” Han, 29, told Coconuts. “So you are almost forced into opposition rather than engagement — which could have just as easily happened.”

But besides facing backlash for their work and trying to bring about social change they believe in, many of the so-called naysayers have very little in common, Vincent says.

“I was interested in showing that there is a spectrum to naysaying,” he said. “Some people are willing to work with the government because you can get change quicker that way, and there are also people who say ‘I’m not going to play by their rules’.”

Publisher Edmund Wee says one reason he wanted to publish Naysayers was because it tackles the myth that disagreeing with an official policy somehow makes a person a radical.

“So many of the people in this book are not anti-government at all,” said Wee. “They are just saying ‘look, we need different views because society is different.’”

Han and her colleague, historian Thum Ping Tjin — also profiled in Naysayers — faced pushback earlier this year during Singapore’s public hearings on fake news. Their application to register New Naratif’s parent company for official status in Singapore was rejected by The Accounting and Corporate Regulatory Authority (Acra) in an unusually public way.

“There was a full page spread in The Straits Times, with these massive photos of us,” said Han. “It said that we were being used by foreigners to carry out political activity in Singapore and it was angled as a suspicious thing.”

The fact that bureaucratic matters like these rarely get this much space in the national paper made readers wonder if the story was not part of a personal attack against Han and Thum. The two have a history of challenging authorities in print including a New Naratif article that ran afoul of Singapore’s official version of history.

But for Dr. Thum, challenging the official narrative is critical for the country’s survival.

“I think history shows us that strong societies require diversity to thrive.”

He says that changes in the region may soon force Singapore to face its indecision between supporting naysayers and suppressing them.

“Perhaps for the first time in our history, Singapore is surrounded by democracies,” said Thum, 38. “These countries are now tolerating dissent through which opposing parties can win power.”

As these other Southeast Asian countries deregulate their political spheres, Thum says, Singapore may be forced to do the same in order to keep up.

“If we remain this very stifling environment, other countries won’t just pass us, a lot of our talent will just go where it is more welcome.”