Cooped up in a cozy office deep in Toa Payoh is a close-knit team keeping Singaporeans educated, informed and entertained – in braille.

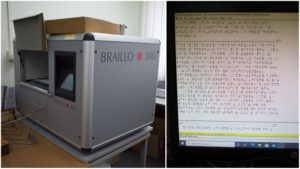

Converting one textbook at the Braille Production Center can take months, even with the help of a bulking machine that costs tens of thousands of dollars. Translating a dictionary? That request was a first – and one that might take too much precious time.

Inside the Singapore Association Of The Visually Handicapped, five of the eight-strong team are visually impaired – including head Edwin Khoo, braille transcriber Jason Setok and librarian Kelvin Tan – and rely on touch and sound and gadgets like braille displays and text-to-speech tech to carry out this exacting work.

“The fact of the matter is because people like us, we use our ears a lot so for the blind the chances of us damaging our ears are also there as well. It’s quite scary actually. Just imagine, if we lose our sense of hearing, braille also comes in as a very crucial medium for us to communicate effectively,” said Khoo, who has just left the association after over a decade.

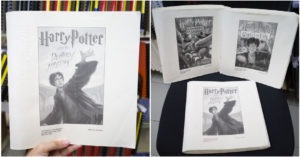

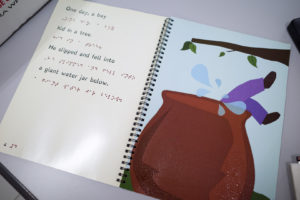

They toil at what is the country’s sole braille facility serving the community by transcribing text and diagrams of everything from school textbooks to Harry Potter novels into braille.

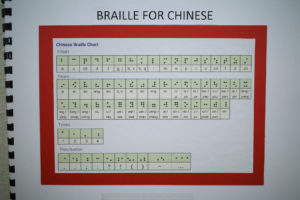

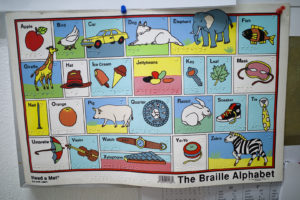

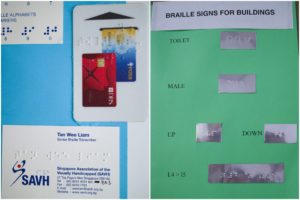

Braille is a system of six raised dots with 63 possible combinations that was invented in 1824. It is available in various languages including Mandarin and Tamil, but English is the default version in Singapore. With braille, one can read with their fingers and play card games and even Scrabble.

The team sits atop a hill on the second story of one of the association’s bleach-white buildings in Toa Payoh. That’s also where my terrible sense of direction prompted a lovely receptionist and other clients – all blind – to guide me with vivid directions.

“It’s over there! Walk out, go up the steps and turn left,” a man holding a white cane pointed out.

Once my inept, sighted self entered the space’s narrow hallways and carpeted floors, I was greeted by Ng Tay Swee Kim, a braille transcriber and pioneer who’d been with the association since 1976. She, together with Indira Premraj, who has five years of transcribing experience under her belt, are in charge of embossing school textbooks, name cards, birthday cards, and knocking out signs in braille.

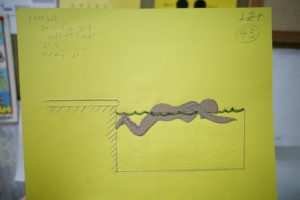

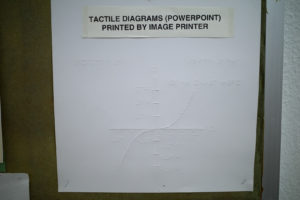

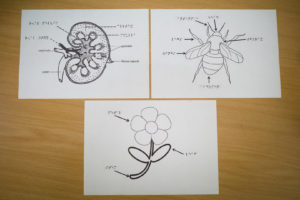

Their speciality? Dotting out diagrams in braille. Indira, 31, described the difficult work as “all just a big mess.”

“We have to scan the diagrams also, we have certain graphs. We cannot just superimpose them on the PowerPoint, we have to redraw the whole thing. Like geography is one of the most difficult ones to do, because they have hundreds of structures of all the different kinds of grid forms for countries and planets,” she said.

That’s why one school textbook can take months, she added. A page will take up about three pages in braille, and that itself takes an hour.

The center mainly supports Ahmad Ibrahim Secondary School and Bedok South Secondary School where visually handicapped students are posted to. They also convert exam papers and worksheets into braille with the help of around 10 volunteers who edit the text to perfection.

A client even requested for an entire English dictionary to be translated to braille, Ng said. Not sure how long that will take.

This tedious work is dotted out by heavy duty equipment, with the biggest one costing over S$60,000 shipped in from Norway. Two others are stored away in a room — one used for textile diagrams and the other for A4 size books.

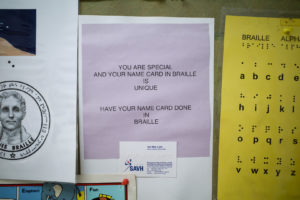

When they’re not racking their brains trying to convert a math graph into braille, they also transcribe the kind of signage one might see in lifts and toilets, decals on ATMs and name cards for anyone who requests. More than 40 companies have approached them just for name cards.

Contractors and companies also bring their signatures or products down to the team to make sure that the braille dots make sense. Apparently, some don’t.

“Not only that my side has a lift where the braille is wrong. For level 21, they put it as level 10. I have actually sent it in to the town council but I don’t see the change being done yet. It’s still the same wrong braille,” Indira said, referring to a lift somewhere in western Singapore that she saw just after joining the team in 2017.

Library of dots

In a separate nearby building housed a library filled with over 400 braille book titles that have been translated or donated to the association. The total number of books, however, is more than twice that. One instalment of the Harry Potter series in braille can comprise 10 volumes that weigh 10 kilograms because of how much space braille requires per word.

A nifty braille device is also available for those who prefer reading from soft copy documents online. The panels with braille dots that readers can feel and scroll through, however, cost thousands of dollars.

“There are braille formats that actually can be cast onto a braille display, so imagine it’s like a word document, just that it is formatted to braille. Basically, instead of a screen, it is a panel with dots that can go up and down. So that’s why we call it a soft copy braille book as well,” said librarian Kelvin Tan, 39, who was a frequent library visitor from his youth.

But of course, now with the vastness of technological options, the blind can also choose to rely on audio books. Tan thinks the availability of these luxury tech options are making the blind read less.

“Definitely the number of people reading is decreasing. Even for me when I was young, I used to borrow braille books but I started to switch to audiobooks back then, it was cassettes and CDs, so I started to listen. So what happened? Spelling becomes lousier, that’s a fact,” he said.

Learning braille

On average, it takes about six months to fully master the art of English braille.

That’s how long braille transcriber and star pupil Jason Setok took when he picked up braille as a survival skill. He lost his sight at the age of 27 because of glaucoma, a condition that damages the optic nerve.

“The reason why I want to learn braille is because if I don’t then who is going to help me? For example, when I’m taking the lift alone myself and there is braille on the lift buttons that’s where braille comes in handy,” Setok, 42, said.

Kelven Chow, a center client, also took under a year to familiarize himself with braille. He didn’t waste any time after he was diagnosed with myopic degeneration over a decade ago and took up braille to prepare for the future.

Chow has been attending practical lessons at the center once every week to hone skills he first took up online.

“Learning early while you are still ‘sighted’ would actually prepare you not to be afraid when ‘darkness’ started to appear, because you already learned the basics for people who are visually impaired, and this would also allow you to be even more confident in the event of total blindness,” the 28-year-old said.

The center continues to support the visually handicapped, who are entitled the right to gain literacy, by equipping them with skills like braille to continue in Singapore’s workforce.

“All this ostracism shouldn’t happen to people who have a disability because people who don’t have a disability will not understand. Actually, we are still capable of doing our job but we just need more time. People process sensory problems differently,” Chow added.

More photos:

Other stories you should check out:

Glass galore: Whimsical works by famed sculptor Dale Chihuly arrive at Gardens by the Bay (Photos)

The peril, pain and elusive profit of minting NFTs, as told by two Singaporeans

Drug-dealing Singaporean Instagram accounts shut down by the dozens