OPINION — Despite all our gripes and grouches about National Service (and its yearly reservist call-ups) it’s widely regarded as A Good Thing for a variety of reasons: Singapore has too small a population to rely on citizens volunteering for the military, it forces people from different backgrounds to assimilate, etc. etc.

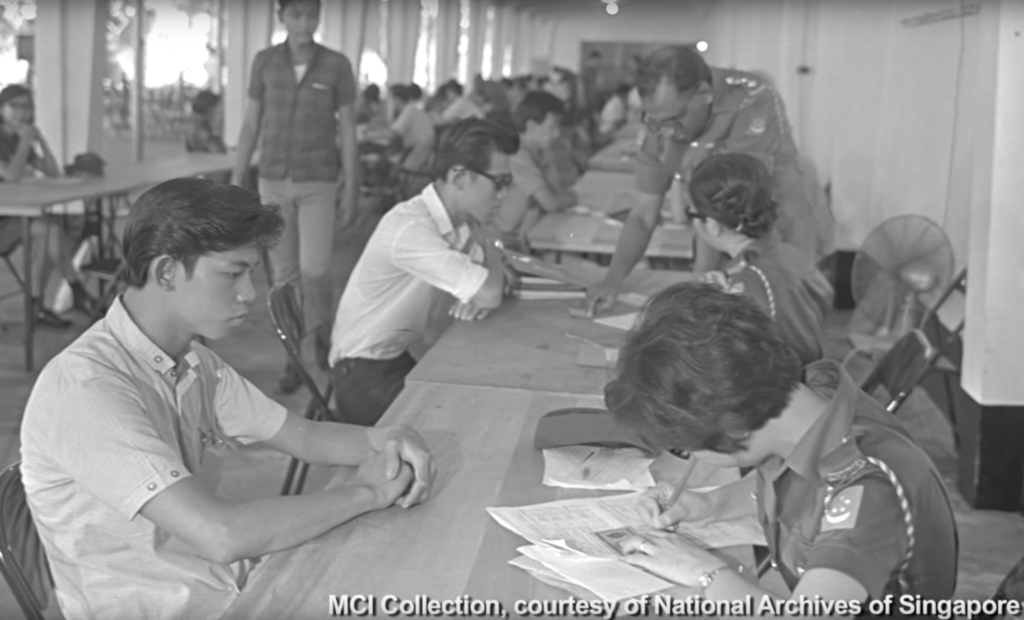

It’s been 50 years since mandatory conscription came into effect, and it’s become a cultural phenomenon unique enough to inspire films and literature revolving around national service. Criticisms abound, of course, but nobody can deny that Singapore stands ready when disaster (or God forbid, war) goes down.

NS50, the year-long commemoration of National Service’s 50th anniversary, however does not bring back warm nostalgic memories for all Singaporean men. We’re not even talking about recalling the time you messed something up and caused everyone else to be punished, nor the time you wore the same dirty underwear for a week straight in the field — we’re talking about structural discrimination that disadvantaged people based on their race.

Suspiciously missing from all the NS50 bluster and forced pride is the fact that Malay youths were virtually (not officially, mind you) excluded from conscription from 1967 till 1977.

Even when they were eventually let in, they were mainly positioned to serve in the police force or the fire brigade. The small minority of Malays who manage to be called up into the military were given menial jobs, and are (almost always) excluded from key defense roles such as intelligence, the air force, commandos, artillery units and more — a practice that arguably continues to this day.

The Ministry of Defence keeps insisting that the selection of personnel in various military vocations is not based on race. “The ethnic composition of commanders is similar to that in the general population,” Minister for Defence Dr Ng Eng Hen said in a 2014 response to a Parliamentary query about the racial breakdown across National Service vocations.

The unofficial, widely understood reason is this: There is uncertainty as to where the loyalties of the Malay community lie should Singapore engage in war with neighboring Muslim-majority countries such as Indonesia and Malaysia.

Alon Peled, an associate professor and political scientist at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, noted in his paper (A Question of Loyalty: Ethnic Minorities, Military Service and Resistance) that discrimination against Malays in the military didn’t need to be spoken out loud to be felt.

“By the second half of the 1970s, Malay exasperation with military recruitment and discrimination polices reached an all-time high. Even without official data, Malay parents knew that their children alone were not called upon to serve. Malay officers and (non-commissioned officers) who had been transferred from field command positions to the logistics corps were also frustrated. Nearly every officer knew that military units had informal quotas on Malays.”

Though pleas were made to Malay leaders to change things, the figures of the day didn’t help ease the malaise. They stated that Malay youth lacked education and couldn’t speak English well (even though drafted Chinese Hokkien youth were the same). They argued that the government didn’t have enough facilities to train Malay soldiers (even though race should make no difference to when it comes to military training).

It may not be much of an issue today, but the impact of Singapore’s blatant exclusion of Malays in the service back then was severe. Tania Li argues in her book Malays in Singapore: Culture, Economy, and Ideology that it left the Malay community behind in socio-economic standing.

“There was an unfortunate side effect to the non-recruitment of Malays into National Service. Employers in Singapore are generally unwilling to recruit or train young male workers who have not completed National Service or obtained exemption papers as these youths can be called up at any time. Since Malays were not officially exempted from National Service, Malay youths were unable to obtain apprenticeships or regular jobs, and many were forced into an extended limbo period of about 10 years from ages 14 to 24 … (this) was in part responsible for the high percentage of Malay youths who became involved in heroin abuse during the late 1970s”.

Peled repeats similar sentiments.

“Malay servicemen were pushed out of the military, and young Malays found that the military doors, once their prime avenue for social mobility and a promising career, were firmly closed. Years of exclusion resulted in social bitterness, frustration and a major collision between the state and its principal ethnic minority group”.

The silent ostracizing did not last, fortunately. Policies were eventually eased as the Malaysian invasion threat diminished, and Malay citizens were slowly integrated into the military. By the 1980s, more Malays were being posted in sensitive positions, including the Commando Battalion, while more began graduating as officers.

The memories of the past however are hard to erase, and for former Straits Times’ senior political correspondent Ismail Kassim, the ongoing NS50 campaign did nothing but revive painful memories. Nonetheless, he asserts that it’s a good time for the government to make amends for the past wrongdoings.

“Surely it is not beyond the ability of the present star-studded scholar-leaders to think of some way to assuage the hurt of the past.”