It was a date night he could never forget. Nirej Tamilrajan had gotten into a cab after saying goodbye to his fiance when the driver asked him a pointed question: “Why? Not enough Indian girls for you to date is it?”

Throughout the rest of his cab journey home, Nirej, who is of Indian descent and engaged to a woman of Chinese ancestry, tried explaining to the driver that not all relationships must be bound by the same culture and religion. The driver was unconvinced.

“I was very taken aback by that question. I told him no, I didn’t fall in love with her because she’s Chinese, but as a person. Then I had to like, case in point, argue with him that it has nothing to do with race,” he told Coconuts Singapore in a recent interview.

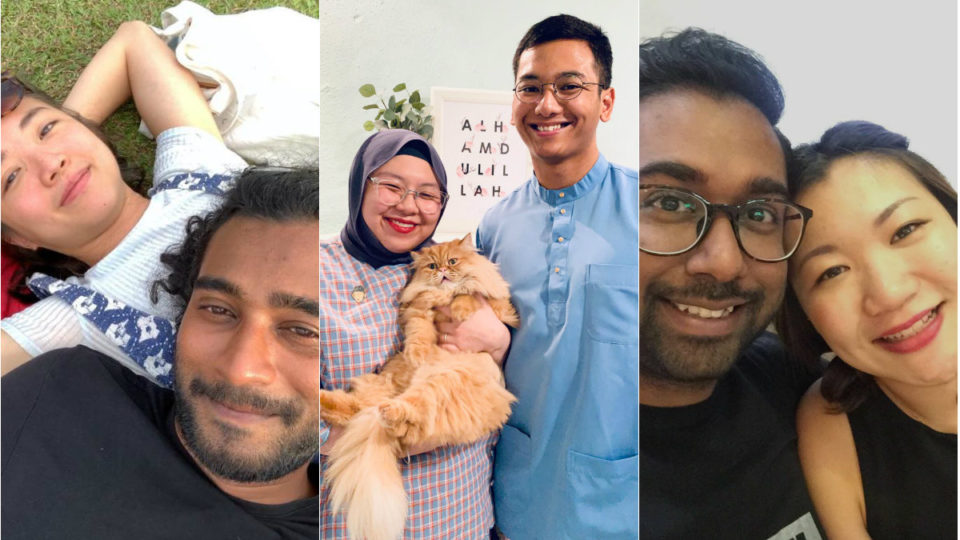

Both the 32-year-old sales executive and his bride-to-be Rachel Ng grew up in families that rarely saw racial differences as barriers. Outside of their families, however, that reality can be quite different, especially for those who find love outside the deeply entrenched boundaries that persist despite Singapore’s racial diversity.

According to five couples interviewed for this story, the racism directed at them in subtle and overt ways is blunted by greater contact between groups, particularly at a young age.

“Racism is not something you are born with, racism is something that is taught. It’s all about upbringing for me, the only way your kids will learn is through teachings of your parents, they have to have learnt [racism] from somewhere,” Nirej said.

When they marry, Nirej and Ng will join an increasing number of interracial marriages in Singapore. The estimated 3,840 “inter-ethnic” couples, as they’re defined on paper, who tied the knot in 2018 was an increase of 6% since 2008. When adjusted for population, however, it remains relatively unchanged.

But even as more people marry into other cultures in Singapore; which is predominantly Chinese, Malay and Indian; interracial marriages are frowned upon or just unfamiliar and distant to others.

Nirej blames it on racism.

Nirej said he was always taught to look beyond a person’s skin. His own parents, who came from different parts of India, had been victims of racial prejudice within their own family in Singapore, leading his North Indian mother and South Indian father to flee to Malaysia to get married.

Nirej said he and Ng met on a dating app and went on their first date a month later.

“I guess through this relationship, racism is a lot easier to handle when your parents are supportive of your relationship. Otherwise, it’s a lot tougher and challenging,” he added.

Enduring enmities

The racism that led to riots and death and Singapore’s expulsion from Malaysia six decades ago remain its original sin. Despite laws under the Sedition Act and Penal Code meant to codify racial harmony, lingering tensions and resentments break out regularly in episodes of acrimony.

Last year, it was national broadcaster Mediacorp hiring an ethnic Chinese actor to appear in brownface for an ad. Two performers of Indian descent were given a conditional warning for responding with a video deemed offensive to the Chinese population. Just last month, a publisher pulled a children’s book deemed racist for pitting a dark-skinned bully with unclean and curly hair against his lighter-skinned classmates.

But given the law and prevailing attitudes that overt displays are unacceptable, interracial couples encounter a racism that is likely subtle and even pervades their families and friends, a psychology lecturer said.

Peter Chew of James Cook University said friends and families may object to interracial relationships due to significant differences in culture, religion, or even dietary requirements. But, the 33-year-old lecturer said, it is difficult to determine whether those reasons “serve as a ‘cover’ for underlying racist attitudes.”

Nadirah Tan, 28, admits that things can get tricky during family dinners, especially when the Muslim convert and home business owner joins her Buddhist family for a steamboat.

Growing up in a Chinese-Buddhist household, Tan married her Malay-Muslim boyfriend of seven years and converted to Islam, switching to a halal diet and not mixing crockery.

“Though it’s a one person pot steamboat, I find it a hassle to wash if everything is half halal and half non-halal, so I told my sister my reasons and they got a bit awkward when I said don’t eat,” she said.

Chew, who studies social and cognitive psychology with an emphasis on race relations in Singapore, notes that couples may be treated differently in public.

“For example, they might receive a second look or even uncomfortable stares from strangers,” he said.

Speech therapist Clare Ee, 29, had to bear racially offensive comments from her own patients when the topic of her love life comes up.

After mentioning that her husband Prasad V is ethnically Indian, she said patients have questioned why she chose to marry him, or even worse, expressed hope her child would not have dark skin.

Ee thinks that some of her patients may never have been told that it was not OK to say such things, which makes it all the more important to speak up.

“From their point of view, they probably meant well, but from my point of view it’s very offensive,” she said. “If we can and we do have the space to voice out then sure, especially since we are in a majority race, we have a duty to speak up for minority races because they might not be able to do that themselves.”

Closing the gap

Speaking up helped Ee persuade her parents to embrace her relationship with Prasad, who did not convert from Hindu to Catholic. Her parents were initially concerned that their differing faiths could prove untenable.

“My parents were worried that if you’re from a different religion, it’s hard to worship together. You don’t share the same faith, you go through high and low points in life together but you can’t fall back on the same religion,” she said. “They were just worried that it would be an issue for us as a couple and that it would pose as a barrier between us.”

For artist A’shua Imran, it took years of bringing home women of other races and faiths for his strict Muslim parents to accept them.

“It’s only at the initial stages when it [was] new for my parents to meet my girlfriend from a different race and religion,” said A’shua, who’s been dating a woman named Jacelyn Chua for the past year. “After that, my parents started to get used to it and realized that they are similar to us.”

Ee and A’shua’s experiences seem consistent with what studies say, that contact can reduce prejudice.

“Contact causes a reduction in prejudice and individuals low in prejudice seek out such contact,” Chew said. “Contact provides us with opportunities to learn more about the individual as a person and could potentially dispel negative racial stereotypes.”

But when communication ends badly, it can worsen relations.

“There is an important caveat though,” Chew said. “Negative contact with other races has the potential to entrench negative racial stereotypes and increase prejudice.”

National Serviceman Syafii, 20, who is Malay and in his first interracial relationship, thinks people should be willing to learn and teach each other if they want to close the gap.

“If X doesn’t understand Y’s culture, it should not just stop there it should be okay to ask why and understand more. And Y needs to be willing to teach and explain to X about why it is like that,” he said.

But where conversations fail, nurturing the next generation to be more racially sensitive may be the best way forward. After all, an individual’s ability to stereotype is usually learned from parents and peers in school, according to Chew.

“While we are able to identify racial differences from a young age, the idea that certain races are associated with certain traits and are therefore superior/inferior is learned,” he said. “If we grow up in an environment where parents and peers would express racist attitudes or behaviors, it is likely that we will model our thoughts and behaviors after them.”

Indeed, nearly all the couples interviewed for this story, including Nirej and Ng, said they were influenced by growing up in open-minded families with friends who mingled outside their groups.

“The best way for parents to nurture the kids is by exposing them to people of different races and leading by action, instead of sitting down and telling them you should not do this and that,” A’shua said.

Other stories you should check out:

Mediacorp actor Dennis Chew says he is ‘deeply sorry’ over ‘brownface’ ad

Police investigating rap video made in response to ‘brownface’ ad for ‘offensive content’

Publisher sorry if readers ‘misunderstood’ racist book for Singapore’s kids

Xiaxue deletes racist posts, cites past sexual assault to vilify ‘Group B’

Singapore Poly looks into racist Instagram posts linked to student

Want to better understand race in Singapore? Here are 101 places to start.