Should I really feel this comfortable strolling through a cemetery this late at night?

It’s the thought that keeps recurring as I walk close (but not too close) to the tombstones, some nearly 70 years old, their carved inscriptions in Jawi and Malay indecipherable in the dark.

In one of the most light-polluted places on Earth, it’s weirdly enjoyable to be engulfed in darkness, nary a street lamp in sight — nary a soul for that matter, or at least ones we can see.

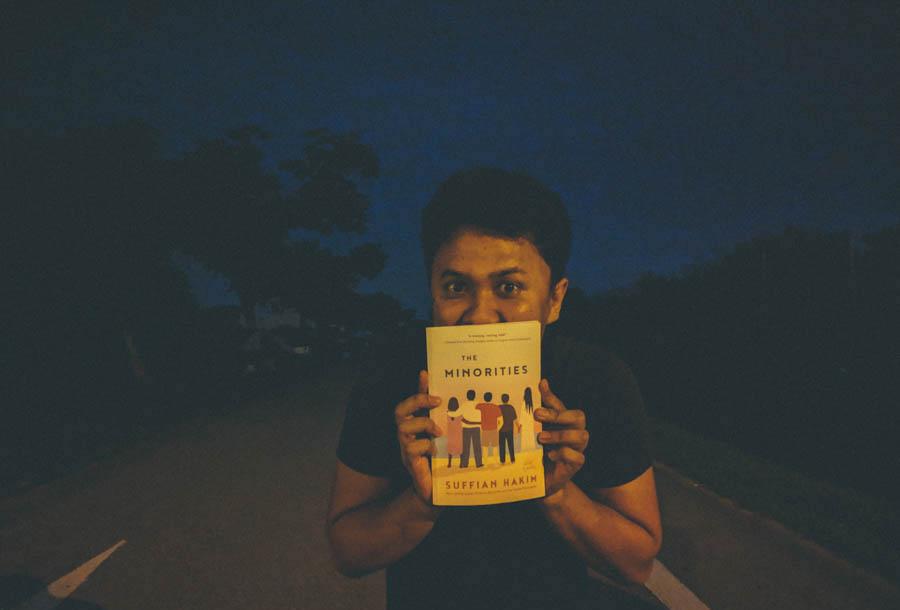

Strolling next to me is Suffian Hakim, the 31-year-old author, and humorist behind blogposts-turned-novel Harris Bin Potter and the Stoned Philosopher, who reimagined J.K. Rowling’s fantasy saga as a Singaporean adventure featuring a Malay boy wizard.

Suffian is also clearly at ease as we saunter among the gravestones, holding forth into the night air with the ease of a seasoned orator. His girlfriend, Shelby Sekar, walks a bit ahead of us — more curious than cowed by our roaming late-night interview inside Choa Chu Kang Muslim Cemetery.

Suffian pauses for a moment as we begin chatting about his new book, The Minorities.

“Do you see that dog there?” he asks, his voice cracking just a bit while gesturing to a stray black mutt sniffing a patch of grass a couple of meters away.

For a second, I consider messing with him and responding “What dog?” before deciding it might be an inappropriate setting for spectral dog humor. I assure him that I also see the pooch in question and continue walking.

So why a cemetery? We’ll forgive you for thinking our conducting an interview here among the dearly departed is a bit gimmicky, but I assure you there is a point beyond mere shits and giggles.

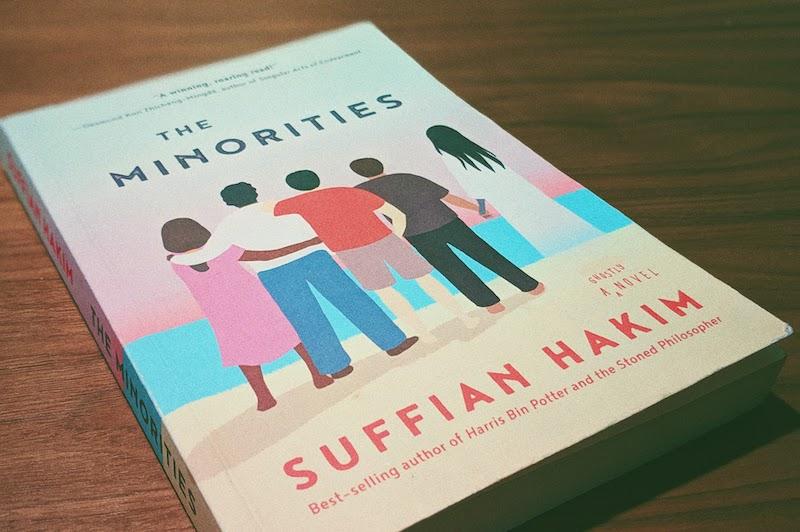

Published by Singaporean indie outfit Epigram Books, Suffian’s latest, The Minorities, follows the story of four individuals living in Yishun (naturally), with the central protagonist being an unnamed narrator born of a Malay-Muslim father and a Chinese-Jewish mother.

When the book opens, the narrator has inherited a Yishun flat from his recently deceased father, and to fill the dad-shaped hole in his life, decides to illegally sublet some rooms to a trio of housemates.

There’s a Bangladeshi construction worker named Cantona, who ran away from abusive employers to pursue his dream of becoming an artist; a Chinese illegal immigrant and superhero fan who dubs himself Tights; and a laboratory technician from India named Shanti, who’s on the run from her abusive gangster husband.

There’s actually one more key character: a pontianak. One of the more fearsome creatures in Singaporean myth, the pontianak is a vengeful female spirit, a woman who died while pregnant and now haunts the land as a violent specter, determined to suck blood and steal babies.

In Suffian’s story, Tights incurs the wrath of one such creature when he takes a shit on the tree where the spirit resides, leading it to haunt the motley crew in their home.

Being broadminded types, they eventually befriend the ghost and embark on an epic road-trip to take the spirit back to its birthplace, Malacca, a journey that involves gangsters, immigration authorities, and a host of Asian supernatural entities wanting freedom from their own bondage.

It’s a bumper crop of pulp fiction elements to cram into one book, something Suffian manages to do with his trademark humor and whimsy. But underneath the layers of comedy and fantasy lies a deeper social examination of what it means to be The Other.

“Friendship is at the heart of it all, but I’m also exploring themes of identity, ethnicity, and assimilation,” Suffian says. “The supernatural beings for example — I use them as an allegory for the truly marginalized groups in humanity. Groups that people pretend don’t exist; groups that are ignored by the majority of society.”

He pauses his train of thought long enough to say hello to an elderly Chinese uncle — presumably a gravekeeper — who passes us on a rickety bicycle, mumbling something incoherent as we walk deeper into the graveyard. Suffian laughs at the surrealness of the situation before continuing.

“I guess what I’m really trying to explore is what the meaning of humanity is underneath skin colors, social status and spirituality,” he says.

The fact that the two main characters are migrants, a group often seen as occupying a lower rung on Singapore’s social ladder, is intentional, he explains. Like the spirits presumably hovering around us in the cemetery, migrant workers –who routinely fall victim to mistreatment and crippling debt at the hands of illegal brokers – bear their very real burdens while invisible to broad swathes of society.

I asked if the theme of being on society’s fringes came naturally, though I already knew the answer.

“These are themes that I’ve been faced with my entire life,” he says, gesturing Shelby to move aside to let a car pass, its headlights briefly blinding us in the dark.

“The idea that I’m a Malay-Muslim, with brown skin affecting how and where I stand in this world… It’s a defining experience in my life, and I wanted to explore that with other permutations, like Bangladeshi construction workers,” he explains.

“These are all people who — because of where they were born, the color of their skin, their social status — their experiences in life become limited.”

Singaporeans, you’ll likely admit, have a habit of “othering” minorities from an early age, something obvious in our social media posts, the offhand remarks some of our parents make, and the jokes we tell each other.

It’s also visible in our common language, Suffian says, bringing up how we are familiar with ingrained derogatory terms such as “apu neh neh” to describe Indians and “mats” for Malays. The unconscious act of marginalizing even extends outside our borders, as evidenced by the recurrent dislike for mainland Chinese folks and other foreigners.

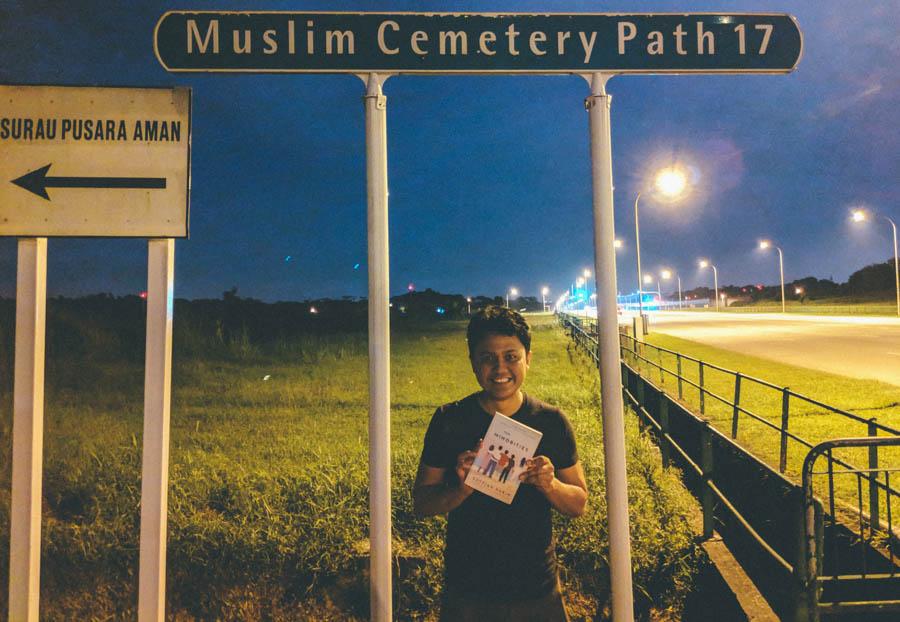

We make a left turn onto Muslim Cemetery Path 18 and Suffian recalls that he heard there are some roads that even the cemetery staff don’t dare enter after sunset.

“Oh, we’ll be fine,” Shelby cheerily remarks, puncturing the drama.

Tempting fate, I snap a picture of a sheltered rest area, and examine my screen, hoping the image hasn’t captured anything unnerving. The picture turns out fine, ghost-free and oddly well-lit thanks to our Pixel 3’s night mode. Blurry though.

Suffian takes the moment to detail why supernatural elements play such a big part in his book.

“I wanted to explore the frustrations a supernatural being would face,” he said with a laugh, joking how spirits should be practical in their choices of places to haunt — an H&M store, for example, would make for better afterlife threads.

What starts as a comedic bit quickly segues into the similarities he sees between ghosts and those we marginalize.

“Both are beings treated as the unseen by most of society, both are trying to hold on to the things that make them human,” Suffian says. “The connecting ectoplasm between apparitions and the marginalized? They’re both holding on tightly to their identity and humanity.”

We make another turn onto a narrow walkway, a path that hems us in between row after row of Muslim tombstones shrouded with tattered white cloth. So far so good, I think — nothing’s out to disturb us tonight.

We delve into the subject of pontianaks, and he mentions how surprised he was to find so many versions and interpretations of female wraiths across different cultures during his research for the book.

In a previous meeting, I had told Suffian about how a LASALLE College of the Arts lecturer had an academic analysis of the pontianak folklore (which interprets the myth as a symbol for the powerful, overtly-sexual-thus-dangerous female).

“I guess being surrounded by countries where science and technology haven’t advanced as much as Singapore creates a heightened sense curiosity [about] a fear of the supernatural that is still prevalent there,” he offers.

In a way, it’s also connected to our sense of superiority, I venture, one that allows a privileged majority to marginalize and disregard sections of the population as backward.

As the silhouette of the Surau Pusara Abadi, the small mosque near the entrance where bodies are washed before burial, suddenly looms closer, I realize we’ve nearly completed our loop around the cemetery, half disappointed and half relieved by what turned out to be a specter-free experience.

“I don’t know if I should say this right now, but I’ve never had a supernatural experience,” Suffian admits as we end our walk. “But I have friends — who I completely trust and believe — who did. So the fact that they would say it suggests… you know, there might be such things.”

Such things, sadly, didn’t reveal themselves during our nighttime trek. Then again, maybe the ghosts identified with Suffian’s words as they echoed across the cemetery.

Or perhaps they just felt a kinship with three minorities searching for deeper meaning amid their final resting place, searching for an exit, searching for a ride out of here.